MRSA as a Public Health Concern in Medical Facilities

Edited by Tommy Brown

Introduction

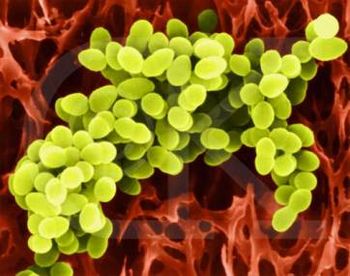

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a type of staph infection that is especially resistant to a wide number of antibiotics, including methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin. [1]. As with most multi-drug resistant pathogens, MRSA is difficult to combat once contracted because the normal regimen of drugs does not work [expand]. With the increased use of antibiotics, with a number of different pathogens there has been seen an increase in drug-resistant strains, such as with MRSA, Tuberculosis and [?]. Many credit the overuse of antibiotics as the main cause for this increase in resistance, but as is discussed below, there are a number of compounding factors. Acquiring MRSA has been associated in two different environments: community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) and healthcare-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA). This article’s focus is on HA-MRSA, to learn more about CA-MRSA, click here. The Center for Disease Control defines HA-MRSA “in persons who have had frequent or recent contact with hospitals or healthcare facilities (such as nursing homes or dialysis centers) within the previous year, have recently undergone an invasive medical procedure, or are immunocompromised,” [2]. HA-MRSA constitutes 85% of all MRSA infections in the United States [2] and there has also been an observable increase in number of cases. A study done over the past seven years has shown a significant increase of MRSA in hospitals, from 4.5/10,000 in 2002 to 19/10,000 in 2009 [3]. Additionally, a similar study concluded that not only are MRSA infections increasing as a problem in hospitals, but are becoming the most common form of staph infection, from 35.9% of S. aureus infections in 1992 to 64.5% in 2003 [10].

MRSA in the context of healthcare

Why HA-MRSA is unique

Due to the opportunistic nature of MRSA, healthcare environments present a unique risk for spreading and contracting the disease. Many patients in hospitals have either open wounds or breaks in the skin such as intravenous lines (IVs) and catheters that leave them especially susceptible to infection. Additionally, nearly half of all in-patients and almost all intensive care unit patients are on some form of antibiotics , reducing the body’s natural flora found on the skin which works as a natural barrier to the disease, compounding their vulnerability to the disease. The most common ways to contract MRSA in a healthcare environment are contact, whether direct or indirect, with a contaminated object, infected person or with someone that is colonized by the disease but not infected. It is estimated that between 2-7% of the US population are colonizers of MRSA [6], and thus without proper care for maintaining a sanitary and sterile environment, it is relatively easy for someone that is immunocompromised or otherwise vulnerable to contract the disease upon exposure to it. One has the ability to infect someone without themselves presenting any symptoms, making MRSA a dangerous threat in a medical environment because it is possible for healthcare personnel to be carriers for the disease without them knowing.

-More on how HA-MRSA is much more resistant and why

How HA-MRSA presents itself

MRSA generally enters the body through openings in the skin, such as cuts or openings for an IV. As a result, the first signs and symptoms of infection are similar to that of a normal skin infection, such as swelling, puss, redness and sensitivity. However, as the disease progresses more systemic symptoms begin to appear such as fever, pneumonia, bacteremia (infection of the bloodstream), sepsis and if left untreated, organ failure and death. This is not to say that all MRSA infections lead to death, but if left untreated and allowed to go systemic, MRSA can present serious complications beyond a normal skin infection. This is especially the case with HA-MRSA due to the fact that it strikes those who are already immunocompromised or vulnerable.

Relationship between CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA

Since the first case of MRSA was reported in the United Kingdom in 1961 [7], it was thought that it was a disease limited to the health-care environment, a nosocomial infection. At the time, doctors believed that it was a relatively common infection that only presented itself in those that were immunocompromised or were otherwise vulnerable, and thus its impact was limited to hospitals and long-term care facilities. However, since the first case of CA-MRSA was reported in 1980, there has been a steady rise in CA-MRSA cases across the country and the world. A recent retrospective study looked in to what percentage of MRSA cases were truly HA-MRSA and which were CA-MRSA [7] in order to determine the prevalence of CA-MRSA outside of the healthcare environment. While the majority of the cases in the study were indeed HA-MRSA, 44.9% of the cases were CA-MRSA, indicating that CA-MRSA is indeed a public health threat within the community, not just in a healthcare setting. The results of the study also supported the conclusion that “CA-MRSA infection is not a nosocomial strain which originated in local healthcare facilities, but a distinct clone that has developed and is being propagated within the community” [7]. While CA-MRSA presents its own unique public health challenges, the study raised concerns that CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA may exchange genetic material to produce more aggressive and more resistant strains of MRSA, as well as increasing the possibility of exposure to MRSA by a patient in a hospital now that CA-MRSA is presenting outside of a healthcare environment. A study conducted last year addressed this second trend, confirming that “CA-MRSA appears to cause healthcare-onset infections, a finding that emphasizes the need for infection control measures to prevent transmission within healthcare settings” [9]. A similar study made similar conclusions, though going as far to say “MRSA with a CA-MRSA phenotype has become the most common cause of HA-MRSA infections [in our hospital],” [11], clearly showing a trend in the interconnectedness CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA.

Increasing Resistance of HA-MRSA

-Why medical facilities are a dangerous environment for a multi-drug resistant microbe

How did MRSA evolve in to the multi-drug resistant strain it is today?

Since the discovery of penicillin and other antibiotics, there was a significant period of time when antibiotics were viewed as ‘cure-alls’ for infection, and “there was a feeling of complacency between the 1940s-190s, with a misplaced belief that available antibiotics would always effectively treat all infections,” . However, the over-prescription of antibiotics, especially in cases where the person would have likely beat the infection on their own anyway, led to an increase in resistance to the normal regimen of antibiotics, most notably methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin.

-Talk about people not following through on their drug therapies, allowing populations of bacteria to rebound, now resistant to that antibiotic

Public Health Recommendations for Combating HA-MRSA

As more research is done in understanding MRSA and HA-MRSA specifically, it is becoming increasingly evident that prevention is the most effective solution, both from a health stand point and a financial one. Due to the resistant nature of MRSA, treatment generally lasts longer and can include second a