MRSA as a Public Health Concern in Medical Facilities

Edited by Tommy Brown

Introduction

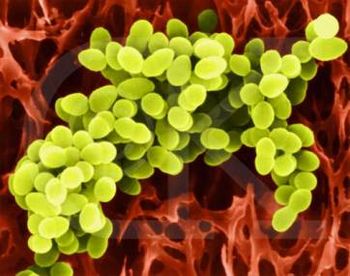

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a type of staph infection that is especially resistant to a wide number of antibiotics, including methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin. [1]. As with most multi-drug resistant pathogens, MRSA is difficult to combat once contracted because the normal regimen of drugs does not work due to resistance within the bacteria. With the increased use of antibiotics, a number of different pathogens have seen an increase in drug-resistant strains, such as with MRSA, and Tuberculosis. Many credit the overuse of antibiotics as the main cause for this increase in resistance, but as is discussed below, there are a number of compounding factors. Acquiring MRSA has been associated in two different environments: community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) and healthcare-acquired MRSA (HA-MRSA). This article’s focus is on HA-MRSA, to learn more about CA-MRSA, click here. The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines HA-MRSA “in persons who have had frequent or recent contact with hospitals or healthcare facilities (such as nursing homes or dialysis centers) within the previous year, have recently undergone an invasive medical procedure, or are immunocompromised,” [2]. HA-MRSA constitutes 85% of all MRSA infections in the United States [2] and there has also been an observable increase in number of cases. A study done over the past seven years has shown a significant increase of MRSA in hospitals, from 4.5/10,000 in 2002 to 19/10,000 in 2009[2]. Additionally, a similar study concluded that not only are MRSA infections increasing as a problem in hospitals, but are becoming the most common form of staph infection, from 35.9% of S. aureus infections in 1992 to 64.5% in 2003 [10].

MRSA in the context of healthcare

Why HA-MRSA is unique

Due to the opportunistic nature of MRSA, healthcare environments present a unique risk for spreading and contracting the disease. Many patients in hospitals have either open wounds or breaks in the skin such as intravenous lines (IVs) and catheters that leave them especially susceptible to infection. Additionally, nearly half of all in-patients and almost all intensive care unit patients are on some form of antibiotics [1], reducing the body’s natural flora found on the skin which works as a natural barrier to the disease, compounding their vulnerability to the disease. The most common ways to contract MRSA in a healthcare environment are contact, whether direct or indirect, with a contaminated object, infected person or with someone that is colonized by the disease but not infected. It is estimated that between 2-7% of the US population are colonizers of MRSA [6], and thus without proper care for maintaining a sanitary and sterile environment, it is relatively easy for someone that is immunocompromised or otherwise vulnerable to contract the disease upon exposure to it. One has the ability to infect someone without themselves presenting any symptoms, making MRSA a dangerous threat in a medical environment because it is possible for healthcare personnel to be carriers for the disease without them knowing.

HA-MRSA Resistance and its Impact

Resistance in MRSA, like many other pathogens such as Tuberculosis, has developed for a number of reasons but can mainly be attributed to overuse of antibiotics [15]. Since the discovery of penicillin and other antibiotics, there was a significant period of time when antibiotics were viewed as ‘cure-alls’ for infections, colds, the flu and other cases where antibiotics were either unnecessary or ineffective; “there was a feeling of complacency between the 1940s-190s, with a misplaced belief that available antibiotics would always effectively treat all infections,” [2]. However, the over-prescription of antibiotics, especially in cases where the person would have likely beaten the infection on their own anyway, led to an increase in resistance to the normal regimen of antibiotics, most notably methicillin, oxacillin, penicillin and amoxicillin. In addition to unnecessary prescription of antibiotics, patients not following through on treatment by not taking the prescribed dose of antibiotics can cause their pathogen to reemerge with a new resistance to the antibiotic prescribed.

Antibiotics are not only present in medication but have been shown to appear in groundwater and streams as a result of runoff from livestock farm where antibiotics are heavily used. Our bodies take in these antibiotics, needlessly, and expose bacteria to them, allowing them to build resistance as well [15]. Overuse of antibiotics cannot be placed with the entirety of the blame, however, as almost all pathogens have a tendency to mutate on their own to develop resistance, and thus overuse of antibiotics might have only expedited the inevitable.

The resistance of HA-MRSA can also partly be blamed on the setting. As mentioned above, nearly half of all in-patients and almost all intensive care unit patients are on some form of antibiotics [1]. Research has shown that use of certain antibiotics, such as fluoroquinolones and cephalosporin, can actually increase the chance of contracting HA-MRSA [15]. Also, a hospital provides a prime environment for MRSA to further develop drug-resistance due to the widespread use of antibiotics in patients as well as prime hosts in the form of other vulnerable patients.

How HA-MRSA presents itself

MRSA generally enters the body through openings in the skin, such as cuts or openings for an IV. As a result, the first signs and symptoms of infection are similar to that of a normal skin infection, such as swelling, puss, redness and sensitivity. However, as the disease progresses more systemic symptoms begin to appear such as fever, pneumonia, bacteremia (infection of the bloodstream), sepsis and if left untreated, organ failure and death. This is not to say that all MRSA infections lead to death, but if left untreated and allowed to go systemic, MRSA can present serious complications beyond a normal skin infection. This is especially the case with HA-MRSA due to the fact that it strikes those who are already immunocompromised or vulnerable.

Relationship between CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA

Since the first case of MRSA was reported in the United Kingdom in 1961 [7], it was thought that it was a disease limited to the health-care environment, a nosocomial infection. At the time, doctors believed that it was a relatively common infection that only presented itself in those that were immunocompromised or were otherwise vulnerable, and thus its impact was limited to hospitals and long-term care facilities. However, since the first case of CA-MRSA was reported in 1980, there has been a steady rise in CA-MRSA cases across the country and the world. A recent retrospective study looked in to what percentage of MRSA cases were truly HA-MRSA and which were CA-MRSA [7] in order to determine the prevalence of CA-MRSA outside of the healthcare environment. While the majority of the cases in the study were indeed HA-MRSA, 44.9% of the cases were CA-MRSA, indicating that CA-MRSA is indeed a public health threat within the community, not just in a healthcare setting. The results of the study also supported the conclusion that “CA-MRSA infection is not a nosocomial strain which originated in local healthcare facilities, but a distinct clone that has developed and is being propagated within the community” [7]. While CA-MRSA presents its own unique public health challenges, the study raised concerns that CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA may exchange genetic material to produce more aggressive and more resistant strains of MRSA, as well as increasing the possibility of exposure to MRSA by a patient in a hospital now that CA-MRSA is presenting outside of a healthcare environment. A study conducted last year addressed this second trend, confirming that “CA-MRSA appears to cause healthcare-onset infections, a finding that emphasizes the need for infection control measures to prevent transmission within healthcare settings” [9]. A similar study made similar conclusions, though going as far to say “MRSA with a CA-MRSA phenotype has become the most common cause of HA-MRSA infections [in our hospital],” [11], clearly showing a trend in the interconnectedness CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA.

Public Health Recommendations for Combating HA-MRSA

As more research is done in understanding MRSA and HA-MRSA specifically, it is becoming increasingly evident that prevention is the most effective solution, both from a health stand point and a financial one. Due to the resistant nature of MRSA, treatment generally lasts longer and can include second- and third-tier drugs that are generally more expensive and have greater side effects. While there are advancements in treatment, MRSA has proved to be relatively quick to mutate. The good news, though, is that HA-MRSA is preventable. By following the CDC guidelines, as well as those put out by the American Medical Association (AMA) and other groups, it is possible to reduce not only MRSA but other opportunistic infections in hospitals.

Reduce Chance of Contact

Studies have shown that increasingly CA-MRSA brought in to the hospital is a leading cause of outbreaks of HA-MRSA [9][11]. Therefore, one of the simplest and easiest ways to curb patients from contracting MRSA is to take steps to reduce the change of contact with the bacterium. MRSA is more easily transmitted when the five C’s are present, a guideline created by the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS)[2]:

- Crowding

- Frequent skin-to-skin Contact

- Compromised skin (cuts or abrasions)

- Contaminated items and surfaces

- Lack of Cleanliness.

These guidelines apply to the many places where such situations are common, such as schools, dormitories, households and daycare centers, but can also be applied to hospital settings, especially in patient placement. The CDC recommends, if possible, that patients with MRSA or are suspected to be either infected or colonizers be placed in single rooms and to reduce transporting them in order to reduce the potential contact other patients might have with them [14]. Additionally, the CDC has outlined guidelines for reducing contact between patients through the simple use of gloves and gowns [14]. Using barriers between the healthcare worker and the patient is important in preventing the healthcare worker from becoming a carrier of the pathogen between patients. Another way of reducing the chance of contact is to try and control the contact a patient has with those that are colonizers of MRSA but are asymptomatic, such as healthcare workers, as raised by a recent MedScape Article[12]. The idea would be to regularly test health care workers to see if they were carriers for MRSA but were not presenting symptoms, with the hopes of preventing them from passing it on to patients. As the author notes however, studies [13] have shown that less than 2% of HA-MRSA cases are from asymptomatic healthcare workers and thus this approach would be unnecessary when there is strict adherence to sanitary guidelines.

Adherence to Guidelines on Sanitary Conditions

The CDC has stated that “the main mode of transmission of MRSA is via hands which may become contaminated by contact with a) colonized or infected patients, b) colonized or infected body sites of the personnel themselves, or c) devices, items, or environmental surfaces contaminated with body fluids containing MRSA,” [14]. It also points out that following general principles for preventing the transmission of microbes, such as consistent hand washing and wearing gloves, can greatly prevent the spread of MRSA. However, it has identified specific procedures that can be especially helpful in preventing the spread of MRSA within a hospital. Consistent hand hygiene, first and foremost, is the easiest way to combat the spread of MRSA within a healthcare setting. The CDC recommends [14] washing hands before a procedure, even if gloves are worn, in addition to after the procedure and between patients. While health care workers have been known to spread MRSA because they themselves are colonizers, the vast majority of HA-MRSA cases are spread between patients by healthcare workers’ hands without themselves being the colonizers. In addition to spreading pathogens between patients, inadequate hand washing can spread pathogens (MRSA included) on to medical equipment that will be used on multiple patients. A good example would be making sure to disinfect one’s stethoscope with a low- to mild-disinfectant between patients, but especially when a patient is suspected of having MRSA. Thus, hand washing is of the utmost importance, not to mention the simplest and cheapest way to prevent spread of MRSA, as well as proper decontamination of medical equipment. Maintaining a generally clean and sterile environment is also important in preventing the spread of any pathogen within a hospital. The CDC recommends [14] that hospitals prioritize rooms of known MRSA patients to be cleaned at least once a day, concentrating on commonly touched surfaces to isolate the patient’s MRSA to that room and preventing its spread to other susceptible patients. This also goes for equipment in the vicinity of the patient.

Advancement in Treatment

With MRSA showing resistance to more drugs each year, it is important to explore which drugs still work in combating the disease and possibly which drugs that have been shelved for a while are now able to combat the disease once more. The National Institute of Health reports that antibiotics are somewhat more effective in treating CA-MRSA and thus attempts are being made to take a more active approach to CA-MRSA with these antibiotics in order to maintain the effectiveness of last-resort antibiotics that continue to work against HA-MRSA [16].

Conclusion

Despite the scary nature of MRSA and specifically HA-MRSA in its resistance to many antibiotics, research has shown that prevention through adherence to sanitary and contact guidelines work effectively at slowing if not stopping the spread of MRSA in a healthcare setting. Simple things like consistent hand washing pay big dividends in preventing transmission to especially vulnerable patients that typically fall victim to HA-MRSA. While HA-MRSA is showing increasing resistance to the normal battery of antibiotics, strains with resistance to last-resort drugs such as vancomycin are still rare and by cycling through antibiotics being used to combat HA-MRSA as well as taking a more active approach at preventing CA-MRSA from entering a healthcare system, HA-MRSA can still be relatively well managed.

References

[1] "Overview of Healthcare-associated MRSA." Center for Disease Contol and Prevention. National Center for Preparedness, Detection, and Control of Infectious Diseases (NCPDCID), 15 Apr. 2009. Web. 3 Dec. 2009.

[2] Evans, M.D., Richard P. "The silent epidemic: CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA." American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons 5 (2008). American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons. 08 May 2008. Web. 3 Dec. 2009.

[3] "Antibiotic resistance - how did we get to this? - the abridged history of antibiotic resistance." Fleming Forum. Web. 1 Dec. 2009.

[4] "MRSA Transmission." EMed TV. Web. 5 Dec. 2009.

[5] "Comparisons of Community-Associated Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Hospital-Associated MSRA Infections in Sacramento, California." Journal of Clinical Microbiology 44.7 (2006): 2423-427. Web. 6 Dec. 2009.

[6] Image Credit

[7] "Community Strains of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus as Potential Cause of Healthcare-associated Infections, Uruguay, 2002–200." Emerging Infectious Diseases HomeEdition 14.8 (2008): 1216-223. Web. 7 Dec. 2009.

[8] “Changes in the Epidemiology of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Intensive Care Units in US Hospitals, 1992–2003”

[9] “Community-associated Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Isolates Causing Healthcare-associated Infections”

[10] “Should Healthcare Workers Colonized With MRSA Avoid Patients?”

[11] “How Often Do Asymptomatic Healthcare Workers Cause Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Outbreaks? A Systematic Evaluation”

[12] “Information About MRSA for Healthcare Personnel”

[13] “MRSA Infection: Overview”

[14] “Antimicrobial (Drug) Resistance: Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)”

[15] Image Credit: MedScape

[16] Image Credit: Destiny Pharma