Spirulina

A Microbial Biorealm page on the Spirulina

|

NCBI: |

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Bacteria; Cyanobacteria; Oscillatoriales

Species:

Spirulina laxissima, S. platensis, S. subsalsa

Description and Significance

When they were first discovered, Spirulina were thought to be eukaryotes. It was believed they were a type of fungi. However, both phylogenetic and morphological analysis illustrate that these organisms are definitely bacteria. Many genera of cyanobacteria are harmful to humans. Spirulina, however, are unique not only in that they are edible, but also because they provide many health benefits.

Genome Structure

Presently, there is not an extensive body of research on the Spirulina genome structure.

Cell Structure and Metabolism

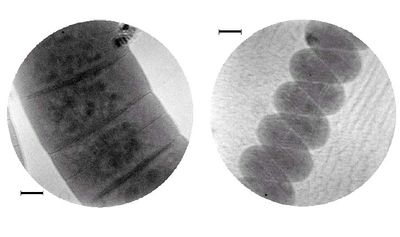

Spirulina are Gram-negative, with soft cell walls that consist of complex sugars and protien. They are undifferentiated and filamentous. Spirulina can be rod- or disk-shaped. Their main photosynthetic pigment is phycocyanin, which is blue in color. These bacteria also contain chlorophyll a and carotenoids. Some contain the pigment phycoythrin, giving the bacteria a red or pink color. Spirulina also have gas vesicles, giving them bouyancy in the aquatic environments they inhabit. Spirulina are photosynthetic, and therefore autotrophic. Spirulina reproduce by binary fission.

Ecology

Spirluina are aquatic organisms, typically inhabiting freshwater alkaline lakes. However, there are marine species as well. They are mesophilic, and able to survive over a wide range of temperatures; some species are even found in hot springs. Spriulina is an edible bacteria. Flamingos get their pink color from eating Spirulina that contain phycoythrin . Humans also eat this bacteria. It is known that the Aztecs consumed it regularly, and it may be an important dietary element in tropical areas. It is also used in Asian cusine. In America, Spirulina is sold in health food stores as a powder or tablet. In Russia, it was approved to treat symptoms of radiation sickness after Chernobyl, because the carotenoids they contain absorb radiation. Evidence shows that it is capable of stopping viral replication. It prevents the virus from penetrating a cell wall and infecting the cell. Spirulina also increase the production of cytokines. This benefit comes from the antioxidants present within the organisms. Spirulina are an excellent source of both protein and iron, and are useful in the treatment of anemia. They can also act as a food source for intestinal flora such as Lactobacillus and Bifidus. Research by Wang et. al. (2005) that this bacteria also slows neurological damage in aging animals, and notes that it can lessen the damage caused by stroke. Studies also show that Spirulina can prevent the release of histamines, treating allergy symptoms. Spriulina has nonmedical uses as well. A study by Chen and Pan (2005) shows that the bacteria can remove low concentrations of lead from wastewater. Research by da Costa and de Franca (2003) illustrates that Spirulina is also capable of removing cadmium from its environment.

References

Australian Spirulina. "How To Compare Spirulina." Accessed 27 July 2005.

Dennis Kunkel Microscopy, Inc.

Speer, Brian R. "Cyanobacteria: Life History and Ecology." Accessed 27 July 2005.

University of Maryland Medical Center. "Spirulina." April 2002. Accessed 28 July 2005.