Zooxanthellae

A Microbial Biorealm page on the Zooxanthellae

|

NCBI: |

Classification

Higher order taxa

Eukaryota; Alveolata; Dinophyceae

Species:

Symbiodinium microadriaticum

Symbiodinium californium

Symbiodinium mustcatinei

Description and Significance

Zooxanthellae species are members of the phylum Dinoflagellata. However, this is not a taxonomic name. Instead, it refers to a variety of species that form symbiotic relationships with other marine organisms, particularly coral. The most common genus is Symbiodinium. Not all Zooxanthellae are endosymbionts; some are free-living. Typically, Zooxanthellae form relationships with organisms simply because they inhabit the same area. However, there are other ways for organisms to acquire Zooanthellae endosymbionts. In the sea anenome Anthopleura ballii, Zooxanthellae are inherited maternally. This, however, is a rare phenomenon.

Genome Structure

There is not yet an extensive body of research on the numerous genome structures within the Zooxanthellae category.

Cell Structure and Metabolism

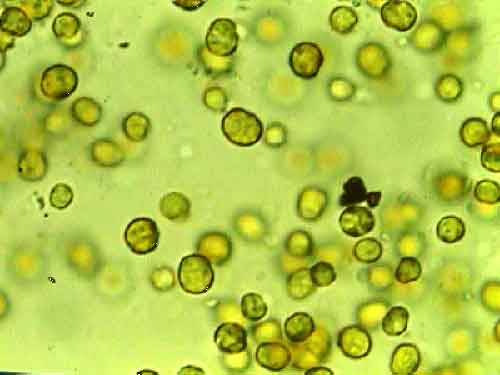

Zooxanthellae are unicellular organisms with a spherical shape. They have two flagella, although these are lost if the organism is acquired by a host. This is called the coccoid state.

Zooxanthellae are mixotrophic organisms. They are mainly photosynthetic organisms (photoautotrophic). However, some species can also obtain food by ingesting other organisms.

Asexual reproduction by division is the most common form of reproduction. Zooxanthellae typically spend their entire life on the organism to which they are attached. The exception is when coral bleaching occurs, and the Zooxanthellae are expelled from the coral.

Ecology

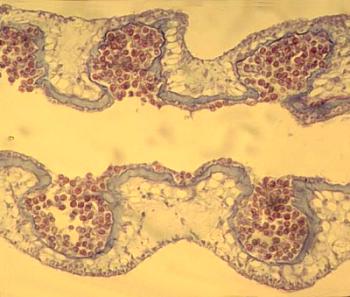

Zooxanthellae are known for their symbiotic relationships with

coral. Zooxanthellae often suffer from bacterial infections that attack

corals. For example, the bacteria that causes Yellow Band/Blotch

Disease (YBD) in Montastraea species actually affects the

Zooxanthellae endosymbionts rather than the actual organism. Many

bacterium interfere with the photosynthetic processes of these

organisms. Zooxanthellae can help host coral harvest light. This helps

the host meet its carbon and energy needs. In addition, Zooxanthellae

give host corals their color. The research of Levy et. al. (2003)

indicates that corals with continuously extended tentacles have denser

populations of Zooxanthellae. Coral bleachings are caused by a

disruption in these relationships. Symbiotic relationships with corals

and other organisms are common in tropical waters with a low abundance

of nutrients. These relationships are significantly less common in

temperate waters.

The Adaptive Bleaching Hypothesis (ABH) suggests that if the loss of Zooxanthellae

occurs due to environmental change, the host organism forms a new

symbiotic relationship with a different type of Zooxanthellae. These

new endosymbionts are blelieved to be better adapted to the new

environment. Other research on the adaptations of coral and

Zooxanthellae suggest that corals that have been damaged due to high

temperatures contain an abundance of Zooxanthellae that are thermally

tolerant (Baker et. al. 2004). The symbiont changes during the stress

period. It is suggested that these corals will be resistant to future

thermal stress because they now have an endosymbiont that will better

help them manage these environmental conditions. Rowan (2004) also

shows that corals adapt to high temperatures by hosting Zooxanthellae

that are specifically adapted to such conditions.

In addition to living in coral, Zooxanthellae can inhabit clams,

nudibranches, flatworms, octocorals, sea anenomes, hydrocorals,

mollusks, zoanthids, sponges, Foraminifera, and jellyfish.

References

Heatherwick, Pete and Sue Heatherwick. "Guide to the Great Barrier Reef." Accessed 5 July 2005.

Ho, Leonard. "Zooxanthellae." March 8, 1998. Accessed 5 July 2005.

Rowan, Rob. "Thermal adaptation in reef coral symbionts." Nature. 12 August 2004;430:742.

Sea World/Busch Gardens Animal Information Database. Accessed 5 July 2005.