Nematode trapping fungi

Introduction

Nematode trapping fungi, or “nematophageous fungi,” are carnivorous fungi that have developed methods and structures that enable them to successfully trap and consume nematodes. Nematode trapping fungi are responsible for keeping the nematode population in check and are an important part of the subsoil ecosystem. These fungi prey on nematodes and are in turn consumed by organisms on the next trophic level. Nematophageous fungi use several methods to hunt their prey. These methods include living within the nematode and slowly consuming them as well as spreading diseases through nematode populations. The fungi also live in the soil and set traps for the nematodes to squirm into.

Biological interaction

Nematophagous fungi and nematodes share a special predator-prey relationship. The nematodes, like many other soil inhabitants, secrete chemicals as they travel through the soil. Fungi that prey upon these nematodes have found a way to detect and respond to the existence of these chemicals.The fungi have also developed many sophisticated ways to trap the nematodes by attacking from both outside and within the nematode.

Detecting the Nematodes

In order to effectively hunt its prey, many species of fungi have developed the ability to detect some of the chemicals that nematodes use to communicate and grow. These chemicals are detected when the nematodes wander too close to the fungus. And if the fungus is in need of nutrients that are not provided in its diet, it will create traps in the area in which it detected the chemicals and thus effectively hunting its prey.

Secretion by Nematodes

Nematodes produce a highly conserved family of small molecules called ascarosides.These small molecules are special to the nematodes and the fungi are able to detect them. Different species of nematode produce different varieties of ascarosides.

Detection by Fungi

Traps to ensnare the nematode are created when these ascarosides are detected.

Trapping the Nematodes

Fungi use many methods in order to ensnare their prey. These fungi can strike from the outside as well as from the inside.

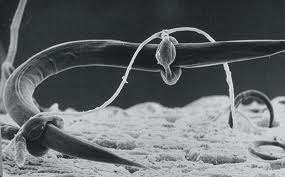

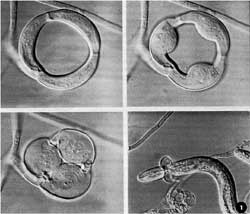

Hyphal Rings

One method used by fungi to trap nematodes is the fungal ring. The fungus produces hyphae that end in an open constricting loop. When a nematode swims through this loop, the loop suddenly fills with water. This sudden change in the physiology of the loop causes the diameter of the inside of the loop to narrow and in turn constricts around the nematode. Within 24 hours, hyphae form from within the loop and penetrate the nematode as it begins to digest it.

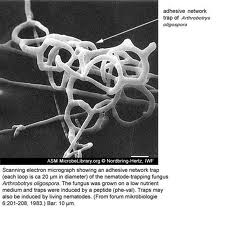

Adhesive Hyphae

Another method commonly used by nematophagous fungi is the use of adhesive hyphae. The fungi who utilize this method create adhesive knobs or nets out of adhesive hyphae. The fungus creates such structures in order to trap the nematode within the structure, and by utilizing the adhesive hyphae the nematode becomes easily ensnared thus providing the fungus with a nitrogen rich meal.

Nematotoxic Compounds

Nematode trapping fungi can use either or both of the methods listed above in order to trap their prey. But some fungi such as the Pleurotaceae family of mushrooms also take it a step further. This family of fungi utilize adhesive knobs to catch nematodes, but once the nematode is caught the fungus secretes a nematacide that kills the nematode and prevents its escape. This extra step is not used by all nematode trapping fungi, but it is utilized by some. It is an extra step of insurance that guarantees that those nematodes that are caught are unable to escape.

Attacking from Within

While many kinds of fungi use traps to catch nematodes, there are also others that live within the nematode and cause damage from there.

Endoparasitic Fungi

Fungi that live within the nematode can infect the nematode at any stage depending on the species of fungus. The infection can be done perorally as in through the mouth or percutanously which means through the skin. From within the nematode, the fungus can consume nutrients meant for the nematode's growth and spread to other nematodes when able. These endoparasitic fungi can spread throughout a community in a measurably short time and spread diseases throughout the process.

Niche

Describe the physical, chemical, or spatial characteristics of the niche where we might find this interaction, using as many sections/subsections as you require. Look at other topics available in MicrobeWiki. Create links where relevant.

Due to the overwhelming abundance of nematodes throughout the world it is easier to say where nematodes cannot be found than to list the many places that they can be found. This being said, the interaction between fungus and nematode is limited to environments where they can both thrive.

Nematode Habitats

Nematodes survive and thrive in almost every habitat on earth. They are present on both land and in aquatic environments. The only stipulation that can limit the spread of nematodes is availability of moisture and prey.

Aquatic Habitats

Nematodes can be found in great abundance in both fresh and sea water. Nematodes can infect aquatic plants and animals.

Terrestrial Habitats

Nematodes can be found in nearly soil on earth. As long as a minimal amount of soil moisture and some sort of organism is present in the soil, it is certain that nematodes can be found there.

Fungal Habitats

Fungi can be found in almost every soil and water source in the world. Although not as enormously widespread and survivable as nematodes, fungi are nearly ever present. Fungi are important to the breakdown of organic compounds and require organic compounds, moisture, and proper pH to survive.

Aquatic Habitats

Fungi can be easily found in both fresh and saltwater sources.

Terrestrial Habitats

Soil is the most common environment for fungi. It is present in some extent in nearly every soil and does the work of breaking down organic materials.

Microbial processes

What microbial processes are important for this microbial interaction? Does this microbial interaction have some ecosystem-level effects? Does this interaction affect the environment in any way? Describe critical microbial processes or activities that are important in this interaction, adding sections/subsections as needed. Look at other topics in MicrobeWiki. Are some of these processes already described? Create links where relevant.

Subsection 1

Subsection 1a

Subsection 1b

Subsection 2

Key Microorganisms

There are many different varieties of nematophagous fungi. And many have yet to be studied extensively. They are present nearly everywhere in the world and have evolved to hunt nematodes in their own way. These nematophagous fungi have evolved alongside the nematodes that they consume and have over time developed methods that are most useful to catch the nematode species that they hunt the most.

Varieties of Nematode Trapping Fungi

Fungal Ring Users

Notable fungi that use a fungal ring include Drechslerella anchonia, Drechslerella dactyloides, and Drechslerella brochopaga.

Adhesive Hyphae Users

Fungi that utilize adhesive hyphae include Dactylellina candida, Drechmeria coniospora, and Arthrobotrys oligospora.

Nematotoxin Users

Notable nematotoxin users include Coprinus comatus, Stropharia rugosoannulata, Arthrobotrys dactyloides, and the Pleurotaceae family.

Endoparasitic Fungi

Fungi that survive as spores in the soil until the time is right include Drechmeria coniospora, Pythium caudatum, and Harposporium leptospira.

Current Research

Due to the over abundance of nematodes and the huge economic loss that is caused by them each year, many experiments are under way in order to find a way to alleviate this damage and promote plant health.

Enter summaries of recent research here--at least three required

"The nematophagous fungus Verticilium chlamydosporizkrn as a potential biological control agent for Meloidogyne arenaria"

The purpose of this experiment was to determine the effectiveness of the fungus Verticillium chlamydosporiu against the nematode against eloidogyne arenaria under greenhouse conditions using tomato plants as a host. It was decided to use three isolates of the fungus. This fungus was riased in a shaken liquid culture of Czapek Dox broth for a week at 18 degrees Celsius. The fungal liquid was then added to a peat/sandy soil and allowed to grow in the greenhouse at 23 degrees Celsius for two weeks. The first experiment involved adding second stage juveniles to the soil of the tomato plants. After 50 days, nematode populations were estimated. For the second experiment, sand and sand/bran mixtures were set up and aliquots of .5 and 5 mL of the nematodes were added to the soil after they had been mixed with fungal particles. This experiment was to determine how well fungal particles of a specific fungal isolate affected the nematodes. The last experiment involved infecting the soil of tomato plants with nematodes but also adding a substantial amount of a fungal isolate. This experiment was to determine if the implementation of either added material affected the plant's growth. Throughout these experiments it was plain to see through the data that was collected that the Isolate 10that was used in the experiments did provide an 80 percent reduction of nematode populations. This isolate also did not cause harm to the plants that it had been planted near.

"Study of the nematicidal properties of the culture filtrate of the nematophagous fungus Paecilomyces lilacinus"

This experiment was conducted to determine which kind of culture of Paecilomyces lilacinu(a nematophagous fungus) was most effective against which varieties of nematodes. Seventeen varieties of nematodes were used throughout this experiment and all of these nematodes were exposed to the filtered filtrate of the fungus. The test was to conclude whether or not the filtrate paralyzed the nematode. This was conducted by exposing all of the nematodes(50 at a time in 20 microliters of water) to the filtrate. After 24 hrs, the nematodes were probed with a sharp needle in order to test for paralysis. Estimates were taken after this 24 hr period in order to determine the number of paralyzed individuals. Several types of medium were also tested to see which method produced the most toxin. The study found that toxin production was not influenced by light or pH, and that the toxin only killed efficiently against the Heteroderidae family.

"Attraction of nematodes to living mycelium of nematophagous fungi"

This experiment investigated how well the bacteria-feeding nematode P. redivivus was attracted to living mycelia of different nematophagous fungi. Methods were developed that allowed the detection of both attraction and repulsion as well as the magnitude of each interaction. The fungi that were involved in this experiment were allowed to grow to nearly the edge of their plates and were grown on various kinds of agar. The nematophagous fungi were also tested with traps present as well as with out traps. The nematode used in the experiment was the bacteria-feeding nematode P. redivivus and it was reared and provided in a way that made it constant throughout the experiment. The attraction assay consisted of adding a drop of the nematode suspension which contained about 100 specimens onto a small round section of the plate after the plate had been dried for 2-3 days. After 24 hours, the remaining nematodes were counted and the attraction/repulsion towards the hyphae was measured. The attraction intensity assay was conducted in the same way as the other experiment, but the nematodes were counted hourly in order to determine how quickly the nematodes traveled towards or away form the hyphae. The experiment ended with a bank of valuable data. It was found through all of the fungi present whether or not traps were formed spontaneously from the introduction of nematodes, attraction vs repulsion, and also attraction vs repulsion after killing the fungi using U.V. radiation.

References

Dayaal R,Mukerji K.G., Saxeena G. "Interaction of nematodes with nematophagus fungi: induction of trap formation, attraction and detection of attractants." FEMS Microbiology Letters. Volume 45. Issue 6. December 1987. Pages 319–327. online. accessed on 4/7/13.<http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0378109787900188>

Glockling S.L., Holbrook G.P.. "Endoparasites of soil nematodes and rotifers 1: the common and the rare."Mycologist. Volume 17. Issue 4. November 2003. Pages 150–154. online. accessed on 4/7/13. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0269915X04004045>

Hauser, J. 1985."Nematode-Trapping Fungi,"Carniverous Plant Newsletter. Volume 14. pg 8-11. online. accessed on 4/7/13.<http://www.carnivorousplants.org/cpn/articles/CPNv14n1p8_11.pdf>

Jacobs P. "Nematophagous fungi - an illustrated overview." April 2002. online. accessed on 4/7/13.<http://www.biological-research.com/philip-jacobs%20BRIC/>

Jansson H.B., Persmark L. "Nematophagous fungi in the rhizosphere of agricultural crops."FEMS Microbiology Ecology. Volume 22. Issue 4. April 1997. Pages 303–312. online. accessed on 4/7/13. <www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0168649697000068>

Yong E. "Worm-Eating Fungi Eavesdrop on the Chemicals of Their Prey." National Geographic. Not Exactly Rocket Science. December 18, 2012. online. accessed on 4/7/13.<http://phenomena.nationalgeographic.com/2012/12/18/worm-eating-fungi-eavesdrop-on-the-chemicals-of-their-prey/>

"WAR of the FUNGI in the MICROWORLD FUNGI versus THE REST." online. accessed on 4/7/13.<http://www.uoguelph.ca/~gbarron/2008/hdiktlis.htm>

Edited by Brad Launer, a student of Angela Kent at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.