Lactobacillus plantarum and its biological implications

Introduction

By Katie Adlam

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki. The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

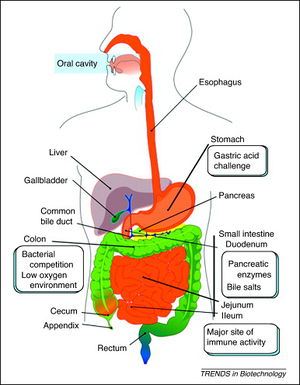

Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) is a rod-shaped, gram-positive lactic acid bacterium from the spirochete phylum. It is common found in the human and mammalian gastrointestinal tract and in saliva, as well as in various food products. It can grow at temperatures between 15-45˚C and at pH levels as low as 3.2 (1). L. plantarum is a facultative heterofermentative (2,3), which means that it ferments sugars to produce lactic acid, ethanol or acetic acid, and carbon dioxide under certain conditions and substrates. Depending on the carbon source, these bacteria can switch from using heterofermentative and homofermentative ways of metabolism. L. plantarum is a current interest to researchers and the food industry since it is considered a safe probiotic. This bacterium is acid and bile salt tolerant, which allows it to survive the passage through the gastrointestinal tract of humans.

Genome

L. plantarum has a relatively large genome compared to other Lactobacillus spp. Its genome consists of a 3.3 Mb chromosome, which is the largest sequenced genome of any lactic acid bacteria (2). The genome of L. plantarum consists of five rRNA operons, which are evenly distributed around the chromosome (FIGURE, 1). 62 tRNA encoding genes have been found and seem to be in relation to some of the rRNA clusters. In addition, the genome encodes two classes of transposase regions, which are thought to encode mobile genetic elements (1).

The genome consists of 3,052 protein-encoding genes and only 39 of these genes are pseudogenes (1). L. plantarum proteins are very similar to other Gram-positive bacteria since they have low GC content, have a peptidoglycan cell wall, and they are organized collinear. L. plantarum genome contains genes for the Embden-Meyerhoff-Parnas (EMP) pathway and some of the genes correlate to enzymes that break down pentoses and hexoses. Furthermore, its genome shows that it has genes that encode for phosphotransferase, mannose, and fructose systems (1).

Metabolism

L. plantarum is a facultative anaerobe or a facultative heterofermentative, as it can grow in the presence and absence of oxygen. It has enzymes for fermentation through the Embden-Meyerhoff-Parnas pathway (FIGURE) or through the phosphoketolase pathway, which allows this bacterium to perform homolactic and heterolactic fermentation (1). When oxygen is not present and this bacterium undergoes homolactic-like fermentation, L. plantarum converts carbon sources to D and L- forms of lactate and alcohols via lactate dehydrogenase. This normally occurs during its growth phase. It is important to note that L. plantarum can use a variety of carbon sources, which has been thought to be a result from horizontal gene transfer.

Under aerobic conditions, lactate is converted to acetate and one ATP is produced via lactate dehydrogenase, pyruvate oxidase, and acetate kinase enzymes. In addition to producing acetate, this pathway also forms hydrogen peroxide and carbon dioxide as byproducts. Hydrogen peroxide is formed by the conversion of oxygen via a manganese-dependent process and the production of this radical species can kill off other bacteria. Manganese-dependent processes use manganese as a catalase to lower the concentration of oxygen, which is beneficial to the aerotolerant bacterium (4). L. plantarum can produce a variety of products from fermentation due to a large “pyruvate-dissipating potential” (1). In addition, research has found that L. plantarum has a fumarate reductase, which implies that this bacterium has a basic electron transport chain (1). It is though that this bacterium possesses a nitrate reduction system, which could use nitrate as an electron acceptor. Furthermore, it does not possess the citric acid cycle, which is a cycle that aerobic organisms use to generate energy through oxidation of acetate.

Metabolism and Secretion

L. plantarum is typically found in a protein-rich environment, such as in yogurt, so it has uptake systems for peptides. Once these peptides are taken up, various types of peptidases degrade them. L. plantarum has 19 different genes encoding peptidases with different specific functions, three of which can cleave N-terminal proline residues. Even though this bacterium has protein degradation mechanisms, it is still capable of producing most amino acids, except branched-chain amino acids such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine (1).

In addition to synthesizing amino acids, L. plantarum also can perform a nonribosomal peptide synthesis (1). Before this discovery, no other lactic acid bacteria was known to use this sort of biosynthesis machinery. The L. plantarum nonribosomal peptide synthesis cluster contains two nonribosomal synthesis proteins, an important phosphopantetheinyl transferase, and proteins that are needed for precursors for regulation, transport, and enzymes (1).

Amino acids and peptides in L. plantarum are transported mainly through 57 ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which 27 are importers and 30 are exporters. Since this bacterium cannot synthesize its own branched chain amino acids, it is able to uptake them through these transporters. In addition, L. plantarum has a high number of sugar import systems and regulatory proteins, which could be responsible for how it is a flexible and versatile bacterium, as it can grow by using different carbon sources and can adapt to a wide array of environments (1).

L. plantarum is known to be able to adapt to stressful environments such as those with a low pH or high salt content. Its genome encodes for proteases that can degrade abnormal or nonfunctional proteins, as well as heat and cold-shock proteins to save energy under stress and to survive different climates. In order to survive in acidic environments, this bacterium uses the FoF1-ATPase and sodium-proton pumps to help regulate and maintain the intracellular pH. Furthermore, it has alkaline shock proteins to assist in pH tolerance. In addition, L. plantarum has developed ways to deal with oxidative stress by having catalases, peroxidases, and reductases, as well as a high intracellular concentration of manganese ions (Mn2+) to scavenge oxygen radicals (1). This bacterium is able to obtain and accumulate manganese ions due to the P-type manganese translocating ATPase.

In addition to being able to adapt to the environment, L. plantarum has surface proteins that allow it to interact with the environment. It has a Sec transport system that is comprised of SecA/SecE/SecG/SecY/YajC (no SecDF) and it also has other proteins involved in secretion such as peptidases (1). In addition, there are genes that encode for a sortase, which is an enzyme that recognizes and cleaves a carboxy-terminal sequences to modify the surface proteins to interact with different surfaces and substrates for growth. Lastly, L. plantarum has a protein machinery that is used to bind and uptake DNA from the environment. Because of this, scientists hypothesize that it acquired its ability to adapt to many different environments. They have found very large regions in genome of L. plantarum where there is unusual base composition when comparing to closely related species such as the genes for sugar uptake and catabolism (1). This reflects how L. plantarum is a very versatile species that can adjust to its environment.

.

Food Production

L. plantarum is commonly involved in dairy, meat, and plant fermentations, and is found in food products such as yogurt, cheese, kimchi, sauerkraut, sourdough, and pickles (3, 5, 6). The bacterium gives food certain tastes and flavors depending on the balance between acetate (volatile) and lactate (nonvolatile) organic acids (2). By using oxygen and aerating food, producers can control the amount of acetic acid that is produced as the final product of fermentation. An example of this is sourdough fermentation.

A specific example of a food item that is produced by L. plantarum fermentation is sauerkraut. Sauerkraut is produced from cabbage spontaneously through lactic acid bacteria that are acid tolerant homolactic fermenters (7). However, the taste of sauerkraut varies depending on the type of bacteria used, the substrate for fermentation, salt concentration, and temperature of the fermentation. Because of the variation, a study set out to find starter cultures that could be universally used for sauerkraut. Leuconostoc mesenteroides (L. mesenteroides) was used for the first phase of fermentation and L. plantarum for the second. L. mesenteroides provides a mild, pleasant aromatic flavor to the sauerkraut while L. plantarum gives it the acidic, vinegar taste. The researchers found that by using both bacteria that the fermentation time was shortened compared to other fermentations (7). In addition, the result of L. plantarum being dominant in the acidic, second phase of the fermentation is that it inhibits the growth of other microorganisms. The two starter bacteria improved the final product of sauerkraut by reducing the fermentation time and the growth of pathogenic microbes.

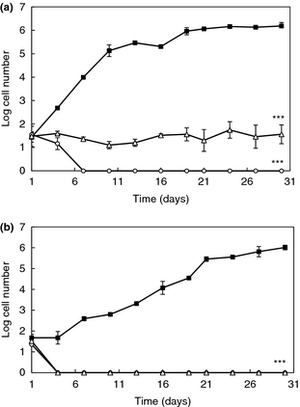

It is also current interest of consumers that more naturally preserved products are available. Because of this, scientists are studying antifungal lactic acid bacteria and their preservative properties. Since lactic acid bacteria typically can survive at wide range of temperatures and pH levels where some food spoilage yeast is found, lactic acid bacteria are being studied to determine if they can inhibit growth of the food spoilage yeast. L. plantarum, a lactic acid bacterium, produces antifungal activity that can be substituted for potentially harmful preservatives that are found in food products (8). A study in 2012 examined L. plantarum to determine if it had the ability to inhibit the growth of Rhodotorula mucilaginosa (R. mucilaginosa), a yeast that spoils dairy products and orange juice, in different refrigerated foods. After isolating and determining the viability of two strands of L. plantarum (strand 16 and 62), this group determined its affect on the activity of R. mucilaginosa by using the antiyeast bacteria as dairy starter adjuncts in yogurt and inoculants in orange juice. Inhibition of R. mucilaginosa was compared against commercial, FDA approved preservatives such as sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate. The study demonstrated that L. plantarum inhibited the growth of R. mucilaginosa and decrease the rate of spoilage in both orange juice and yogurt (Figure, 8). In addition, the inhibition of R. mucilaginosa was more effective than sodium benzoate and potassium sorbate, which means this finding can help increase shelf life of yogurt and orange juice. However, it is important to account that the exact antifungal compounds that L. plantarum produces is unknown and is currently being investigated.

Conclusion

Overall text length at least 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2011, Kenyon College.