Bacillus thuringiensis: Difference between revisions

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Its genome was recently sequenced (February 23rd, 2007). It is critical to have ''B. thuringiensis' ''genome sequenced because it has many benefits for humans in the form of agriculture. ''Bt'' is the most common environmentally-friendly insecticide used and is the basis of over 90% of the pesticides available in the market today. Having sequenced the entire genome, scientists can witness and determine how mutations can create different variant strains that may eventually grow stronger against antibiotic pests. ''B. thuringiensis'' pesticide S-layer (where the Cry protein and toxins lie) has no known negative effects on humans, vertebrates, or plants. | Its genome was recently sequenced (February 23rd, 2007). It is critical to have ''B. thuringiensis' ''genome sequenced because it has many benefits for humans in the form of agriculture. ''Bt'' is the most common environmentally-friendly insecticide used and is the basis of over 90% of the pesticides available in the market today. Having sequenced the entire genome, scientists can witness and determine how mutations can create different variant strains that may eventually grow stronger against antibiotic pests. ''B. thuringiensis'' pesticide S-layer (where the Cry protein and toxins lie) has no known negative effects on humans, vertebrates, or plants. | ||

Many studies indicate ''B. thuringiensis'' and ''B. cereus'' to be | Many studies indicate and consider ''B. thuringiensis'' and ''B. cereus'' to be one species. However, their phenotypes greatly differ in that ''Bt'' produces crystal proteins despite the fact that crystal protein synthesis is controlled by plasmid genes which can be susceptible to loss and transmission to related bacteria. One response, though, is that ''Bt'' strains produce enterotoxins (toxins released by micro-organisms in the lower intestine) that are involved in ''B. cereus'' pathogenesis. | ||

http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html | http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html | ||

Revision as of 10:29, 4 June 2007

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Bacillus thuringiensis

Classification

Higher order taxa

Eubacteria (kingdom); Bacteria (domain); Firmicutes (phylum); Bacilli (class); Bacillales (order); Bacillaceae (family); Bacillus (genus); Bacillus cereus group

Species

Bacillus thuringiensis

Description and significance

Describe the appearance, habitat, etc. of the organism, and why it is important enough to have its genome sequenced. Describe how and where it was isolated. Include a picture or two (with sources) if you can find them.

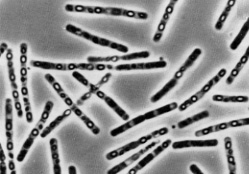

B. thuringiensis (Bt) is a gram positive, soil-dwelling, spore-forming, rod-shaped bacteria. It is approximately 1 µm in width and 5 µm in length. It grows at body temperature and produces a diamond-shaped crystal from its crystal proteins (Cry proteins) and uses it to fend off insects, predators, and other pathogens.

Its genome was recently sequenced (February 23rd, 2007). It is critical to have B. thuringiensis' genome sequenced because it has many benefits for humans in the form of agriculture. Bt is the most common environmentally-friendly insecticide used and is the basis of over 90% of the pesticides available in the market today. Having sequenced the entire genome, scientists can witness and determine how mutations can create different variant strains that may eventually grow stronger against antibiotic pests. B. thuringiensis pesticide S-layer (where the Cry protein and toxins lie) has no known negative effects on humans, vertebrates, or plants.

Many studies indicate and consider B. thuringiensis and B. cereus to be one species. However, their phenotypes greatly differ in that Bt produces crystal proteins despite the fact that crystal protein synthesis is controlled by plasmid genes which can be susceptible to loss and transmission to related bacteria. One response, though, is that Bt strains produce enterotoxins (toxins released by micro-organisms in the lower intestine) that are involved in B. cereus pathogenesis.

http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html

Genome structure

Describe the size and content of the genome. How many chromosomes? Circular or linear? Other interesting features? What is known about its sequence? Does it have any plasmids? Are they important to the organism's lifestyle?

B. thuringiensis has a circular plasmid chromosome. Due to its 2% GC-content, it has more A/G base pairs. Compared to its bacterial relatives, Bt's genome is consiered medium-sized. It genome is only 5,475 nucleotides long, has approximately 2.4 to 5.7 million base pairs [6], and consists of only seven genes: pK1S1_p1, pK1S1_p2, pK1S1_p3, pK1S1_p4, pK1S1_p5, pK1S1_p6, and pK1S1_p7. [7]

(over 200 different insecticidal genes have been identified to date. The largest class consists of the δ-endotoxins, which often are produced as 130–140 kDa protein precursors that are solubilized and proteolytically processed in the insect gut under alkaline conditions to yield a 60–65 kDa biologically active core toxin [3]. δ-Endotoxins have been expressed in cotton, potatoes, rice and corn [4], [5], [6] and [7], with commercial cotton and corn seeds being available for planting in the United States, Canada, Mexico and Japan.)

Cell structure and metabolism

Describe any interesting features and/or cell structures; how it gains energy; what important molecules it produces.

gram positive -> thick cell wall -> peptidoglycan + periplasm(ic space), inner membrane, outer membrane, et al. techioc....

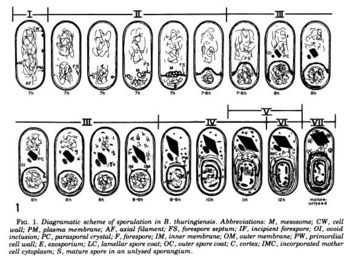

The cell's production of the crystal is very regulated. here is the proces...

Ecology

Describe any interactions with other organisms (included eukaryotes), contributions to the environment, effect on environment, etc.

Several studies have been done on animals to see what the effects of B. thuringiensis are. When treated with 10,000 mg of Bt per kg body weight, autopsy results on birds showed no pathology was attributed. High concentrations of Bt in fish and aquatic organisms failed to show any adverse effects . Experiments performed on other animals showed similar negative results. Conclusion: There seems to be no adverse effects on eukaryotic-celled organisms when exposed to Bt.[8]

Effects on the environment are largely considered mild. It is made from the soil and thrives at body temperature. When exposed to higher temperatures such as sunlight (UV light) however, its half-life greatly decreases to around 3.8 hours. As soon as it is exposed to a warmer-than-normal medium, B. thuringiensis' spores start deteriorating and loses viability within four days. Normally, a short half-life is bad. But in Bt's case, it is actually good in that the short half-life minimizes antibiotic resistance. An additional advantage of its rapid degradation stems from it being readily biodegradable. Possible future reseach in breaking down plastic bags? [9]

Pathology

How does this organism cause disease? Human, animal, plant hosts? Virulence factors, as well as patient symptoms.

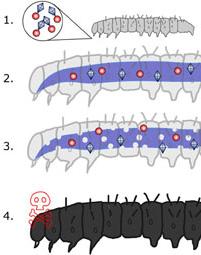

Common insect targets are "including moths, mosquitoes, blackflies, beetles, hoppers, aphids, wasps and bees as well as nematodes"[10]. The toxicity lies in the crystals. Here is a rough map of how B. thuringiensis causes disease.

1. B. thuringiensis is digested and the toxins are mixed with the high pH to bind specific receptors in the gut to attack the host insect.

2. This process punches holes in the gut-lining and thus, the insect becomes weak.

3. As the gut is continuing to break down, spores begin to germinate from the toxic crystals and other bacterial pathogens start to infect the host.

4. B. thuringiensis spores are continuously weakening the host and the insect dies soon thereafter.

Bacillus thuringiensis is very species-specific and does not work with every single host. There are different strains of B. thuringiensis that effect different hosts. For example, "B.t. aizawai (B.t.a.) is used against wax moth larvae in honeycombs; B.t. israelensis (B.t.i.) is effective against mosquitoes", et al. The key is that the host must eat B. thuringiensis "in the immature, feeding stage of development referred to as larvae [because] it is ineffective against adult insects". [11]

Application to Biotechnology

Does this organism produce any useful compounds or enzymes? What are they and how are they used?

It was once thought that B. thuringiensis' method of toxology was via toxin-mediated disruption, which basically consisted of Bt killing the host by starvation or blood poison. However, recent reserach by scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reported having other players involved.[12]

(Soil-transmitted nematode (STN) infections represent a major cause of morbidity in developing countries, with an estimated burden of human disease comparable with that of malaria or tuberculosis (1–3). In addition to human health, animal nematode infections are of major veterinary significance, resulting in millions of dollars of lost revenue for industries that provide products and food from livestock, including cattle and sheep (4–8). Although anti-nematode drugs (anthelminthics) exist, there are well founded concerns about the emergence of resistance to these compounds. Hence, there exists a pressing need to develop new, safe, and inexpensive agents for the treatment of human and veterinary nematode infections of global significance (8–12).)

Current Research

Enter summaries of the most recent research here--at least three required

1. http://www.bt.ucsd.edu/ http://biology.ucsd.edu/faculty/aroian.html

2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=pubmed&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=AbstractPlus&list_uids=17461054&query_hl=1&itool=pubmed_docsum study on maize

3. Find out what Dr. Larsen's lab is doing.

References

National Center for Biotechnology Information

(1) http://textbookofbacteriology.net/Anthrax.html

(2) http://www.bact.wisc.edu/themicrobialworld/structure.html

(3) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genome&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=20524

(4) http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=232943&tools=bot

(5) http://www.bt.ucsd.edu/how_bt_work.html

(6) http://extoxnet.orst.edu/pips/bacillus.htm

(7) http://www.bt.ucsd.edu/what_is_bt.html

(8) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genome&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=20524

(10) http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/genomes/madanm/articles/dnashuff.htm

(11) http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?db=genome&cmd=Retrieve&dopt=Overview&list_uids=20524

(12) http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html

(13) http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html

(14) http://microgen.ouhsc.edu/b_thuring/b_thuringiensis_home.htm

(15) http://pmep.cce.cornell.edu/profiles/extoxnet/24d-captan/bt-ext.html

(16) http://www.nanotechbuzz.com/50226711/bt_microbe_fools_biotech_experts.php

(17)

(18)

(19)

(20)

(21)

(22)

Edited by Ernest Hsu of Rachel Larsen and Kit Pogliano