Bacterial phage defense mechanisms with applications

Overview

Bacteria are constantly subjected to bacteriophages and other selfish genetic elements. Bacteriophages are viruses that specifically infect bacteria and the relationship can be described as a parasitic. This is because bacteria are harmed throughout the phage replication cycle and often lysed when progeny phage particles leave the cell1. Moreover, it is estimated that there are 1030-1032 total phage particles on earth, which outnumber bacteria by 10-fold2. This means that phages are found in almost every environment in which bacteria exist, making virtually all bacteria susceptible to phage infection. In response to this constant exposure to phage, bacteria have evolved several diverse antiviral defense mechanisms. These mechanisms include adsorption blocking, uptake block, abortive infection, restriction modification and the CRISPR-Cas system1. Restriction modification and the CRISPR-Cas system are elaborated on in this article as they are the best understood and important tools in molecular biology.

To date, the genus Ignicoccus is comprised of single cells that are irregularly shaped coccoid ranging in diameter from 1-3 µm. The Achaean genus was first isolated from marine hydrothermal vents from Kolbeinsey Ridge in north Iceland and also off the coast of Mexico [1] (see Figure 1). They were found to have a novel cell envelope unseen before in other Achaea [2], and have a very complex and poorly understood symbiotic relationship with Nanoarchaeum equitans [3] [4] [5] [6].

Key Defense Mechanisms

Restriction Modification

Restriction modification (R-M) is a defense mechanism which is widely spread among bacteria3. There are several types of R-M and all of these typically involve at least two enzymes, a restriction endonuclease (REase) and a methyltransferase (MTase). The REase is responsible for the cleavage of intruding double-stranded DNA, e.g. phage genomes4, through the recognition of the specific nucleotide restriction sites. Upon genome cleavage the phage is not able to finish its life cycle. Methylation of restriction sites by MTase protects the host cell genome from cleavage and REases are categorized as different restriction endonuclease types depending on their specific mode of activity3.

There are three officially recognized Ignicoccus species: Ignicoccus hospitalis , Ignicoccus pacificus and Ignicoccus islandicus . The three species were initially identified by 16S rRNA gene analysis from the hydrothermal vent samples obtained from Kolbeinsey Ridge and the coast of Mexico[1] . All three species have been characterized as hyperthermophiles that are also obligate anaerobes which explains the presence of Ignicoccus species near hydrothermal vents[1] . None of the members of the Ignicoccus genus have been found to be [1] pathogenic to humans.

CRISPR

The CRISPR-Cas system is a mechanism that evolved in bacteria and archea to protect against genetic element intrusion and functions similarly to an adaptive immune system. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR), are loci with several non-continuous direct repeats separated by stretches of variable sequences called spacers7 . These repeat and spacer sequences, along with one or several cas (CRISPR associated) genes, are key elements present in every CRISPR-Cas system mechanism7.

There are three known types of CRISPR-Cas systems as well as several diverse subtypes. The most commonly used CRISPR-Cas system in molecular biology is type II, which is naturally found in Streptococcus thermophiles, a lactic acid bacterium that is important to the dairy industry. Cas 9 is the key enzyme required for the CRISPR system to function and has several enzymatic functions, including endonuclease and integrase activities7,8 . Cas 9 recognizes specific dsDNA sequences in the phage genome called protospacer adjacent motive (PAM), and uptakes a prospacer nucleotide sequence of about 30 bases downstream of the PAM site. This sequence is then integrated by Cas9 as a spacer into the bacterial genome flanked by two repeat sequences. The spacer sequence then gets transcribed into a precursor CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA). The pre-crRNA gets processed by an RNase which is triggered through a transactivating crRNA (tracrRNA) that is complementary to the repeat. The process happens in the presence of Cas 9, which then associates with the processed crRNA 8. Upon re-encounter of the same phage genome, site-specific cleavage by Cas 9 occurs as the target site is determined by base complementarity between crRNA and the prospacer in the phage genome 8.

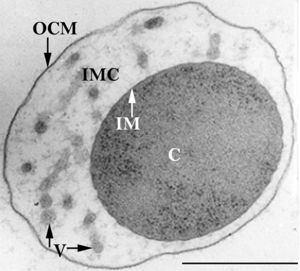

The members of the Ignicoccus genus are motile irregular coccoid cells that range in diameter from 1 to 3 µm. The motility observed is due to the presence of flagella, but unfortunately the polarity of the flagella is not yet fully elucidated. They are known to have an outer-membrane but no S-layer. This is a novel characteristic for these Archaea becauseIgnicoccus are the only known Archaea that have been shown to possess an outer-membrane[2] [10] .

Outer-Membrane

The outer-membrane of Ignicoccus species was found to be composed of various derivatives of the typical lipid archaeol, including the derivative known as caldarchaeol [5] . The outer-membrane is dominated by a pore composed of the Imp1227 protein (Ignicoccus outer membrane protein 1227). The Imp1227 protein forms a large nonamer ring with a predicted pore size of 2nm[7] .

Metabolism

Ignicoccus species are chemolithoautotrophs that use molecular hydrogen as the inorganic electron donor and elemental sulphur as the inorganic terminal electron acceptor[1] . The reduction of the elemental sulphur results in the production of hydrogen sulphide gas.

Ignicoccus are autotrophs in that they fix their own carbon dioxide into organic molecules. The carbon dioxide fixation process they use is a novel process called a dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle that involves 14 different enzymes[8] .

Members of the Ignicoccus genus are able to use ammonium as a nitrogen source.

Growth Conditions

Because members of the Ignicoccus genus are hyperthermophiles and obligate anaerobes, it is not surprising that their growth conditions are very complex. They are grown in a liquid medium known as ½ SME Ignicoccus which is a solution of synthetic sea water which is then made anaerobic.

Grown in this media at their optimal growth temperature of 90C, the members of the Ignicoccus genus typically reach a cell density of ~4x107cells/mL[1] .

The addition of yeast extract to the ½ SME media has been shown to stimulate the growth and increase maximum cell density achieved. The mechanism by which this is achieved is not known[1] .

Symbiosis

Ignicoccus hospitalis is the only member of the genus Ignicoccus that has been shown to have an extensive symbiotic relationship with another organism.

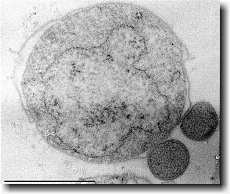

Ignicoccus hospitalis has been shown to engage in symbiosis with Nanoarchaeum equitans . Nanoarchaeum equitans is a very small coccoid species with a cell diameter of 0.4 µm[9] . Genome analysis has provided much of the known information about this species.

To further complicate the symbiotic relationship between both species, it’s been observed that the presence of Nanoarchaeum equitans on the surface of Ignicoccus hospitalis somehow inhibits the cell replication of Ignicoccus hospitalis . How or why this occurs has not yet been elucidated[3] .

Nanoarchaeum equitans

Nanoarchaeum equitans has the smallest non-viral genome ever sequenced at 491kb[9] . Analysis of the genome sequence indicates that 95% of the predicted proteins and stable RNA molecules are somehow involved in repair and replication of the cell and its genome[3] .

Analysis of the genome also showed that Nanoarchaeum equitans lacks nearly all genes known to be required in amino acid, nucleotide, cofactor and lipid metabolism. This is partially supported by the evidence that Nanoarchaeum equitans has been shown to derive its cell membrane from its host Ignicoccus hospitalis cell membrane. The direct contact observed between Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis is hypothesized to form a pore between the two organisms in order to exchange metabolites or substrates (likely from Ignicoccus hospitalis towards Nanoarchaeum equitans due to the parasitic relationship). The exchange of periplasmic vesicles is not thought to be involved in metabolite or substrate exchange despite the presence of vesicles in the periplasm of Ignicoccus hospitalis .

These analyses of the Nanoarchaeum equitans genome support the fact of the extensive symbiotic relationship between Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis. However, it has not yet been proven that it is a strictly parasitic relationship and further research may prove that there is a commensal relationship between the two species.

References

(1) Burggraf S., Huber H., Mayer T., Rachel R., Stetter K.O. and Wyschkony I. ” Ignicoccus gen. nov., a novel genus of hyperthermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic Archaea, represented by two new species, Ignicoccus islandicus sp. nov. and Ignicoccus pacificus sp. nov.” International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2000, Volume 50.

(2) Naether D.J. and Rachel R. “The outer membrane of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Ignicoccus: dynamics, ultrastructure and composition.” Biochemical Society Transactions, 2004, Volume 32, part 2.

(3) Giannone R.J., Heimerl T., Hettich R.L., Huber H., Karpinets T., Keller M., Kueper U., Podar M. and Rachel R. “Proteomic Characterization of Cellular and Molecular Processes that Enable the Nanoarchaeum equitans- Ignicoccus hospitalis Relationship.” PLoS ONE, 2011, Volume 6, Issue 8.

(4) Eisenreich W., Gallenberger M., Huber H., Jahn U., Junglas B., Paper W., Rachel R. and Stetter K.O. “Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis: New Insights into a Unique, Intimate Association of Two Archaea.” Journal of Bacteriology, 2008, DOI: 10.1128/JB.01731-07.

(5) Grosjean E., Huber H., Jahn U., Sturt H, and Summons R. “Composition of the lipids of Nanoarchaeum equitans and their origin from its host Ignicoccus sp. strain KIN4/I.” Arch Microbiol, 2004, DOI: 10.1007/s00203-004-0725-x.

(6) Briegel A., Burghardt T., Huber H., Junglas B., Rachel R., Walther P. and Wirth R. “Ignicoccus hospitalis and Nanoarchaeum equitans: ultrastructure, cell–cell interaction, and 3D reconstruction from serial sections of freeze-substituted cells and by electron cryotomography.” Arch Microbiol, 2008, DOI 10.1007/s00203-008-0402-6.

(7) Burghardt T., Huber H., Junglas B., Naether D.J. and Rachel R. “The dominating outer membrane protein of the hyperthermophilic Archaeum Ignicoccus hospitalis: a novel pore-forming complex.” Molecular Microbiology, 2007, Volume 63.

(8) Berg I.A., Eisenreich W., Eylert E., Fuchs G., Gallenberger M., Huber H.,Jahn U. and Kockelkorn D. “A dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle in the hyperthermophilic Archaeum Ignicoccus hospitalis.” PNAS, 2008, Volume 105, issue 22.

(9) Brochier C., Gribaldo S., Zivanovic Y., Confalonieri F. and Forterre P. “Nanoarchaea: representatives of a novel archaeal phylum or a fast-evolving euryarchaeal lineage related to Thermococcales?” Genome Biology 2005, DOI:10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r42.

(10) Huber H., Rachel R., Riehl S. and Wyschkony I. “The ultrastructure of Ignicoccus: Evidence for a novel outer membrane and for intracellular vesicle budding in an archaeon.” Archaea, 2002, Volume 1.