Bovine Rumen

Biorealm Niche: Bovine Rumen

Description of Niche

What is Bovine Rumen (and other parts of bovine stomach)?

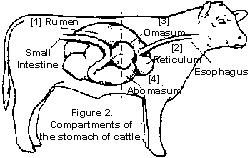

Bovines (of bovinae subfamily) are unique in a way that they have four stomach compartments to digest their food. Those compartments are rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. Of these, rumen is the largest compartment, and it can hold as much as 50 gallons of food and other ingested substances. The most important part about rumen is that it contains huge amount of different microbes, including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Reticulum, or "honeycomb," is the part responsible for rumination (or cud chewing) and trapping hard, indigestible substances like rocks, nails, or wires that may be ingested by accident while the bovine is grazing. If the reticulum gets punctured or injured from metal or other sharp objects, it can lead to traumatic reticuloperitonitis, or "hardware disease," and it is very important that this does not happen (5 Wilson). Omasum, or "many-piles," is a leaf-like folds shaped compartment that acts as a gateway to the abomasum. Its main role is to send back large substances back to rumen and reticulum while allowing smaller, well-broken down substances to pass through into abomasum. Then, abomasum, also called "true stomach," is very similar to human stomach, as it is responsible for producing acids and enzymes to break down proteins, and it sends the chyme to small intestine (2 Hall).

In the rumen, there are billions of microbes living in a symbiotic manner. There are about 25 to 50 billion bacteria and 200 to 500 thousand protozoa. These microbes help the bovine to breakdown ingested food, while the bovine provides them with shelter and nutrients. Without them, bovines would have tough time digesting plant fibers and starches and producing useful fatty acids. Bovines can eat a wide range of feeds because they have many different kinds of microbes to help them digest. They eat and ruminate/regurgitate the incompletely chewed bolus back into the mouth so they can chew again. This process helps the microbes to have access to more finely chewed food in order to make microbial digestion easier. They can even eat urea because the microbes can use non-protein nitrogen to create amino acids. The microbes also produce other essential substances like vitamins B and C (2 Hall).

Although rumen-microbial system is a powerful factory for food consumption, it is also sensitive to sudden changes in feed-types. For example, if the bovine is accustomed to feeding on high levels of fiber and low levels of starch, then the rumen is equipped with more fiber-digesting microbes. Then, if the food content is suddenly changed to high starch and low fiber, the bovine would not be able to properly digest the feeds. This may lead to sudden decrease in pH, as the starch just sits in the rumen and ferments, and can cause harmful illness such as acidosis. Therefore, it is crucial to keep the nutrition of the bovines constant, especially for the domestic cows and oxen (2 Hall).

The bovines are also responsible for producing large amounts of methane gas, due to many methanogens like the strains of Methanobrevibacter, Methanomicrobium, Methanobacterium, and Methanosarcina living in the rumen. About 6% of what they eat gets lost as methane gas. This has been brought up in issues about global warming, and the effects of bovine methane in the environment are currently being researched (4 Whitford).

Physical Conditions

Inside of the bovine rumen tends to have pH at around 6.5 to 7.2. Malnutrition, such as over-feeding of starch, can decrease pH level drastically and can be very harmful for the bovines. 20-35 gallons of saliva produced per day provides sodium bicarbonate to keep the pH consistent for the microbes to grow. Most of water in saliva is not wasted, but recycled in the body (2 Hall).

Since it is inside of bovine body cavity, the oxygen level is low or absent in the rumen, so it is an anaerobic condition. The absorption of the carbohydrates and volatile fatty acids is done by the epithelium of the rumen, which allows the ruminal juices to seep in between the cells. To increase the surface area for absorption, the ruminal mucosa contains numerous conical papillas (5 Wilson).

The temperature of a healthy bovine tends to range from 37.8 °C to 40.0 °C, the core organs being around the high end. Temperature of the bovine depends mainly on body part and time of the day. For body part differential, the closer to the core, the higher the temperature becomes. Thus, temperature of the rumen is around 40.0 °C. Moreover, rumen contents tend to ferment at 40.0 °C, so this works as a central self-heating system. Temperature of the skin can be as much as 10 to 20 °C lower than the core temperature. Furthermore, time of the day makes difference in bovine body temperature. The temperature is usually cooler in the morning after resting and warmer in the night after long day of muscular activity. Recent studies have shown that hormonal interactions after giving birth can affect female cow’s body temperature as well. The range of healthy body temperature is fairly narrow, and thus it is very important to maintain that range in order to carry out normal metabolic and microbial functions (1 Chen).

These conditions show that the microbes in the rumen are obligate anaerobic mesophiles that only grow in non-extreme conditions.

Environment (Bovine Habitat)

Where do they live, and how does that affect their rumen condition? Do any of the physical conditions change? Are there chemicals, other organisms, nutrients, etc. that might change the community of your niche?

Nutrition

What do they eat and how does that factor into type of microbes living in the rumen? What is considered proper nutrition?

Who lives there?

Which microbes are present?

You may refer to organisms by genus or by genus and species, depending upon how detailed the your information might be. If there is already a microbewiki page describing that organism, make a link to it.

Are there any other non-microbes present?

Plants? Animals? Fungi? etc.

Do the microbes that are present interact with each other?

Describe any negative (competition) or positive (symbiosis) behavior

Do the microbes change their environment?

Do they alter pH, attach to surfaces, secrete anything, etc. etc.

Do the microbes carry out any metabolism that affects their environment?

Do they ferment sugars to produce acid, break down large molecules, fix nitrogen, etc. etc.

Current Research

Enter summaries of the most recent research. You may find it more appropriate to include this as a subsection under several of your other sections rather than separately here at the end. You should include at least FOUR topics of research and summarize each in terms of the question being asked, the results so far, and the topics for future study. (more will be expected from larger groups than from smaller groups)

References

1. Chen, Pei Jun. "Temperature of a Healthy Cow". Hypertextbook. <http://hypertextbook.com/facts/1998/PeiJunChen.shtml>. 1998.

2. Hall, John B, Silver, Susan. "Nutrition and Feeding of the Cow-Calf Herd: Digestive System of the Cow". Virginia Cooperative Extension. <http://www.ext.vt.edu/pubs/beef/400-010/400-010.html#TOC>. June 2001.

3. McCowan, R.P., Cheng, K.J., Costerton, J.W."Adherent bacterial populations on the bovine rumen wall: distribution patterns of adherent bacteria".PubMed Central. <http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=291309>. January 1980.

4. Whitford, Marc F, Teather, Ronald M, Forster, Robert J. "Phylogenetic analysis of methanogens from the bovine rumen". PubMed Central. <http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=32158>. May 2001.

5. Wilson, Patrick D. "Bovine forestomachs and stomach". <http://www.vetmed.wsu.edu/van308/bovine.htm>. February 2004.

Edited by students of Rachel Larsen

David Becker , Jin Choi , Sarah Flores , Prema Hampapur , Edmond Ho , Adrianne Kurkciyan , Christopher Park , Brian Sun