Diagnosis and Prevention of Neisseria meningitides Induced Meningitis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:N.meningitidis.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Scanning electron micrograph of Neisseria meningitidis bacteria taken at the University of Wisconsin – Madison. ]] | |||

By Emily Staudenmaier | By Emily Staudenmaier | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

== | ==Classification of ''N. meningitidis''== | ||

<br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | <br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | ||

== | ==Detection and Diagnostic Techniques== | ||

<br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | <br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | ||

== | ==Vaccination Strategies== | ||

<br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | <br>Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.<br> | ||

Revision as of 21:39, 15 April 2009

By Emily Staudenmaier

Introduction

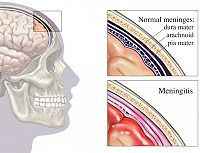

Meningitis is an inflammation of the membrane surrounding the human brain and spinal cord also known as the meninges. Meningitis can be caused by a bacterial or viral infection. Of the two types of infections, bacterial causation generally results in a more severe infection. The inflammation of the meninges results in headache, neck stiffness, fever, sensitivity to light and sometimes vomiting (Slonczewski). These symptoms can progress quickly when bacteria are behind the infection, resulting in death 10-20% of the time (Tzeng). Three species of bacteria, Streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis, are known to cause this infection. Certain characteristics of the latter species, N. meningitidis, result in difficult obstacles when it comes to the development of measures to diagnose, treat and prevent meningitis. Those obstacles and promising solutions are discussed in detail below.

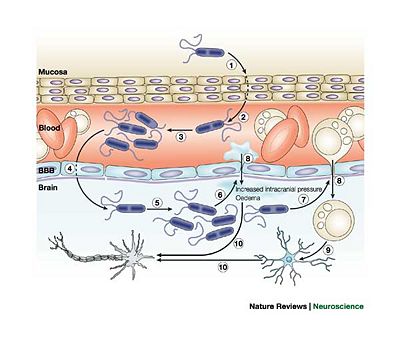

Neisseria meningitidis is Gram-negative, aerobic, nonmotile, coccal bacteria which is pathogenic only to Homo sapiens. Initial infection occurs in the nasopharynx where the bacteria can bind easily to the mucus membrane using their pilli. When present in the nasopharynx, the bacteria typically do not cause serious health problems to the host. In fact, 5-10% of adults have N. meningitidis present in their nasopharynx and do not develop meningitis. The asymptomatic presence of the bacteria can be beneficial to the human host since it allows antibodies to develop that can be useful in fighting a more serious subsequent infection. The entrance of the bacteria into the bloodstream results in serious consequences for the host. N. meningitidis has the unusual ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the cerebral spinal fluid (Tzeng). The mechanism of this infiltration is unknown. Once the crossing has occurred, the bacteria release inflammatory cytokines which leads to the inflammation of the meninges.

Infection is spread through direct contact with nasal or oral fluids contaminated with the bacteria. Inhalation of large droplet nuclei can also result in the spread of N. meningitidis. N. meningitidis induced infections are most common and most serious in children, young adults and the elderly. Children who have lost antibodies from their mother and have yet to gain exposure to asymptomatic infections of the bacteria in their nasopharynx, lack any antibiotic immune response to the presence of N. meningitidis (Sánchez). Young children are therefore the most susceptible age group to contracting meningitis. Many vaccines and medications normally prescribed to fight an N. meningitidis infection are not recommended for children younger than two which further complicates the issue of preventing and curing infection in this age group. Infection rate increases again for the young adult age group due simply to an increased level of exposure and transmission especially on college campuses where people live closely in relatively small spaces. The infection rate is also high in the elderly population. Often the elderly possess weakened immune systems which cause them to be more prone to infection.

N. meningitidis is also unique in that it can cause both epidemic and endemic cases of meningitis. Epidemic outbreaks of meningitis have become a serious issue in developing nations where the supply of vaccines and medication is limited and confined living situations result in increased transmission of virulent strains of the bacteria. One region of Africa has been termed the “Meningitis Belt”. The infection rate in this area can be as high as 1000 cases for every 100,000 people in the population (Tzeng).

Due to the highly infectious nature of virulent N. meningitidis and the quick escalation of the severity meningitis infections, timely diagnostic measures and effective vaccines are essential.

Classification of N. meningitidis

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Detection and Diagnostic Techniques

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Vaccination Strategies

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Conclusion

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Cripps, A., Foxwell, R., and Kyd, J., “Challenges for the development of vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitides”. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2002. Volume 14. p. 553-557

Lansac, N., Picard, F. J., Ménard, C., Boissinot, M., Ouellette, M., Roy, P. H., and Bergeron, M. G. “Novel Genus-Specific PCR-Based Assays for Rapid Identification of Neisseria Species and Neisseria meningitidis”. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2000. Volume 19. p. 443-451.

Sánchez, S., Troncoso, G., Criado, M. T., and Ferreirós, C., “In vitro induction of memory-driven responses against Neisseria meningitidis by priming with Neisseria lactamica”. Vaccine. 2002. Volume 20. p. 2957-2963.

Slonczewski, J., and Foster, J. Microbiology: An Evolving Science. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009.

Taha, M. K., Deghmane, A. E., Antignac, A., Leticia Zarantonelli, M., Larribe, M., and Alonso, J. M. “The duality of virulence and transmissibility in Neisseria meningitidis”. Trends in Microbiology. 2002. Volume 10. p. 376-382.

Tzeng, Y. L. and Stephens, D. “Epidemiology and pathogenesis of Neisseria meningitides”. Microbes and Infection. 2000. Volume 2. p. 687-700.

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2009, Kenyon College.