Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103) and its Probiotic Use

Introduction

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) is a bacterial strain of L. rhamnosus that was isolated in 1983 and filed for patent in 1985 by Barry R. Goldin and Sherwood L. Gorbach (therefore the surname letters GG). It is one of the most widely studied strains for its use in probiotics and it has been rarely known to cause disease or infection. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG primarily exists naturally in the human digestive system, but can also be found in the human urinary and genital systems. It can also be found in various product applications, primarily dairy products, such as yogurt, fermented milk, pasteurized milk, and semi-hard cheese.3 Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG is generally known to help the human body maintain a “good balance” of bacteria to prevent the growth of malignant bacteria in the stomach and intestines.1 Consequently, the use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in probiotics have become popular and has been proven to treat or prevent gastrointestinal diseases and infections, atopic dermatitis, allergic reactions, dental caries, nasal pathogens. Because the probiotic use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG is relatively new, it had not yet been approved by the FDA to treat any disease.1 However, the first commercial use of probiotics with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG was launched in Finland in 1990 under the Gefilus® brand. Recently, new studies have been conducted to find probiotic use in the human oral cavity.

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Scientific Basis and Safety of Probiotic Use

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG is known for its robust character and ability to survive the acid and bile in the stomach and intestine. Furthermore, it is particularly useful in probiotics because of its ability to adhere to cells, colonize the intestine, exclude or reduce pathogenic adherence, persist and multiply, produce acids, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins antagonistic to pathogen growth, resist vaginal microbicides and form a normal, balanced flora. The ability of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and other Lactobacillus species to adhere to intestinal cells promotes a variety of specific interactions with the human host and is one of the most widely studied mechanisms of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.

Genome

Comparative and functional analyses of its genomic sequences have demonstrated some of the molecular mechanisms administrating these host-microbe interactions. In order to characterize the molecular mechanisms between Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and the human host, one study conducted complete genome sequences for Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus rhamnosus LC705 (an industrial strain commonly used in as a starter culture for dairy products). Both strains are among the largest sized lactobacilli genomes, with the genome of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG sized at 3.01 Mbp (average Lactobacillus species genomes are ≈2Mbp, 2,944 genes, and average gene size of 873 bp, and no plasmids. The genome sequencing identified five genomic islands in strain GG that are predicted to encode 80 unique proteins with lengths of 100 residues or more and were not conserved between closely related strains of bacteria, suggesting that they had been transmitted by horizontal gene transfer and exhibit specialized biological functions. They found that the genomic islands in Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG had the capacity to transport or metabolize sugars (GGISL1, LCISL1, LCISL2, and LCISL4), produce specific EPSs (GGISL5 andLCISL3), and 2 islands were enriched with phage-associated genes (GGISL3 and GGISL4). Furthermore, the GGISL2 island contained genes that encoded for 3 pili proteins (SpaCBA) and a sortase, which is required for pili assembly, features that are characteristic of colonization and host-interactions for gram-positive bacteria.

The study also found that compared to other species of lactobacilli, Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG had 143 unique proteins and 24 of them were related to carbohydrate transport and metabolism. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG uses a variety of mono-and disaccharide substrates, which is a metabolic activity considered advantageous for bacteria residing in the carbohydrate-rich proximal regiona of the small intestine. They found that its genome encoded a set of phosphotranferase system transporters (PTS) and carbohydrate-metabolizing enzymes utilized in metabolic network reconstruction. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG genome does not contain the enzymes or transporters to use rhamnose, ribose, and maltose. However, they also identified 40 genes predicted to encode potential glycosidases which may participate in peptidoglycan hydrolysis and the conversion of complex polysaccharides and prebiotics to simple carbohydrates.

Gastrointestinal Diseases and Infections

There are several studies that have reported the use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG to either treat or prevent various forms of diseases and infections in the stomach and intestines. The most common use for Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG is to treat diarrhea symptoms in acute diarrhea, Traveler’s diarrhea, antibiotic associated diarrhea, and gastroenteritis. Most of these studies have been conducted with infants or children.

Acute Diarrhea: The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition conducted the most extensive trial using Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for the treatment of moderate to severe diarrhea in children with 287 children aged 1-36 months from 10 countries. They found that patients who received Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG had decreased severity and shorter duration of the illness, a shorter hospital stay, and decreased likelihood of persistent diarrheal illness than patients who did not take Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supplements. Another study was done with 137 children aged 1-36 months who were admitted to the hospital with diarrhea and the children given Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG had a significantly lower duration of illness. Similar studies have been conducted in Thailand and Pakistan in which treatment with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG substantially decreased duration and severity of symptoms. One preventative study was performed with undernourished children aged 6-24 months in Peru that showed a significant decrease in the rate of incidence of diarrhea among children who received Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG who were not being breast-fed.

Traveler’s Diarrhea: Individuals traveling to less-developed countries with warmer climates may experience the debilitating symptoms of Traveler’s diarrhea, which has been known to occur in about 50% of travelers who visit high-risk areas. One study was conducted in which American tourists were given capsules containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG powder or a ethyl cellulose placebo. The study found that the risk of having diarrhea on any given day was 3.9% for those receiving the Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG capsules compared with the 7.4% for individuals receiving the placebo and the impact of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG did not vary as a function of gender or age.6

Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhea (ADD): Diarrhea has been reported to occur in a little under 20% of patients who clinically use antibiotics.5 ADD is caused by a microbial imbalance that decreases the fermentation capacity of the colon decreases the endogenous flora that is usually responsible for colonization resistance.5 A number of studies have been conducted in the ability of probiotics with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG including a study of 119 children who received antibiotics for respiratory infections and during the first two weeks after antibiotic treatment had an ~70% reduction in diarrheal symptoms than patients receiving the placebo.4 Another study with 202 children receiving oral antibiotics found that 8% of children who received Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with their antibiotics experienced diarrheal symptoms compared with 26% who received the pacebo.5 A study with adults found that patients who received antibiotic treatment to kill Helicobater pylori found that those who received Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG experienced significantly less nausea and diarrhea.5

Atopic Dermatitis

Some studies have been conducted in the use of probiotics with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG in the prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis, primarily with mice and recently some studies have emerged with young children and infants though the yield mixed results. Intestinal mucosa functions as a deference barrier against gut intraluminar antigens and atopic dermatitis is associated with divergent barrier functions of the skin and in some patients, the gut mucosa. The barrier defect in atopic dermatitis may be due to mutations in barrier proteins or may be due to intestinal mucosal damage caused by reactions to food antigens or microbes.

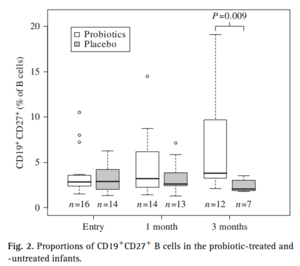

A study was conducted to characterize the interaction of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with skin and gut microbiota and humoral immunity with infants with atopic dermatitis. In a randomized double-blind test with 39 infants, for a period of 3 months they took blood and fecal samples to determine the number of immunoglobulin-secreting cells by enzyme-linked immunospot. They found that the proportions of IgA-and IgM-secreting cells decreased significantly in the group that received Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. They also determined the proportion of CD19+CD27+ B among peripheral blood ceucocytes cells by flow cytometry and characterized major groups of gut and skin bacteria using PCR. They found that the proportions of CD19+CD27+ B cells significantly increased in the treated patients compared to the placebo group. The decrease in immunoglobulin-secreting cells suggests that in the presence of constant stimulation of gut intraluminar antigens, there was an increase in gut barrier function in infants treated with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG. Moreover, the increase in CD19+CD27+ B cells, memory cells that are important in bridging the innate and adaptive immune system, illustrates and important mechanistic effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and indicates an increase in immune response with the use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.

Conclusion

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Lee, Y. K., and Seppo Salminen. Handbook of probiotics and prebiotics. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Edited by (Hannah Whittemore), a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL187S (Microbial Life) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2013.