Lemierre's Syndrome

By Jessie Griffith

Summary of this Article

This article will focus on Lemierre’s Syndrome. This disease has implications for human health, because although it is rare, the disease progresses toward extremely dangerous symptomology that can result in sepsis of the blood and eventually death. The research question that I will be addressing in this paper is how Fusobacterium necrophorum plays a role in Lemierre’s syndrome, and what other conditions can result from this bacterial infection. In this article I hope to demonstrate how an exogenously acquired human pathogen, Fusobacterium necrophorum can cause Lemierre’s Syndrome, and what processes lead toward the various conditions that can stem from this infection. WARNING: the following article may contain images unsuitable for those who are faint of heart, as photographs of the infection will be shown.

Defining Lemierre’s Syndrome

Lemierre’s Syndrome is a post-anginal septicemic infection (Riordan 2007). A post-angial infection is one in which the first symptoms include pharyngitis, and later symptoms include a high fever, cervical adenopathy, thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, and distant abscess formation (Leuger 1995). In lay terms, cervical adenopathy is enlargement of lymph nodes specifically within the neck; thrombophlebitis refers to inflammation of a vein associated with thrombosis, in this case, specifically the jugular vein becomes inflamed. A septicemic infection is one in which the infection or its byproducts enter the bloodstream and cause inflammation throughout the body. Lemierre’s Syndrome is treatable with antibiotics, and some researchers have found that metronidazole is a particularly effective antibiotic for clearing out the infection due to its having a ß-lactamase inhibitor, compared to penicillin, which would need to be paired with another drug to increase its efficacy (Riordan 2007).

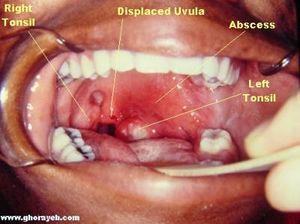

Three terms that will be used in the course of this article are Lemierre’s Syndrome, postanginal sepsis, and necrobacillosis. The three denote relatively the same condition; however there are slight differences between what they can mean when used precisely. Postanginal sepsis refers to the clinical term to describe the condition of complications that arise from peritonsillar abscesses, meaning an infected disease pocket that occurs in the throat near the tonsils (Fig. 1). These abscesses do not need to be caused by an anaerobe such as Fusobacterium necrophorum, but the location and severity of the abscess does need to fit specifically with the definition of postanginal sepsis. Alternatively, the term postanginal sepsis can also refer to the complications that arise from purulent pharyngitis. This term does not denote the presence or lack thereof of Fusobacterium necrophorum. Necrobacillosis, however, does denote the presence of Fusobacterium necrophorum. Necrobacillosis is a blanket term, and can be use to describe infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum in animals or humans. When designating specifically the host, a term such as human necrobacillosis must be used. When an infection of this bacteria leads to peritonsillar abscesses, thrombophlebitis, and septicemia, that is when a clinician would term the disease Lemierre’s Syndrome(Elzubeir 2015).

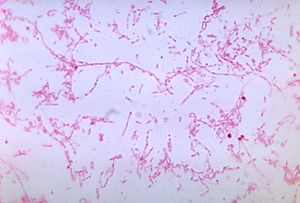

For unknown reasons, Lemierre’s syndrome is a disease that affects young adult males more than any other demographic (Riordan 2007). This incidence in young males over females is very slight, and the small number of samples of this condition make it hard to know for sure whether this is a real demographic difference. It is known that infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum is typically exogenous, but it remains unknown whether transmission between human or from animals plays a role in sourcing the infection. Fusobacterium species are present in the human body at a very low concentration in healthy individuals. The oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and female genital tract are all locations from which Fusobacterium has been identified in healthy individuals (Tan 1996). However, the disease is undeniably rare; some studies rate the prevalence of this condition as low as one in a million (Jones 2001, and Hagelskjaer 1998). The disease is typically caused by a gram-negative, anaerobic, bacilli called Fusobacterium necrophorum, although the presence of this bacteria is not requisite for a patient’s condition to be deemed Lemierre’s syndrome (Fig. 2)(Courmont 1900).

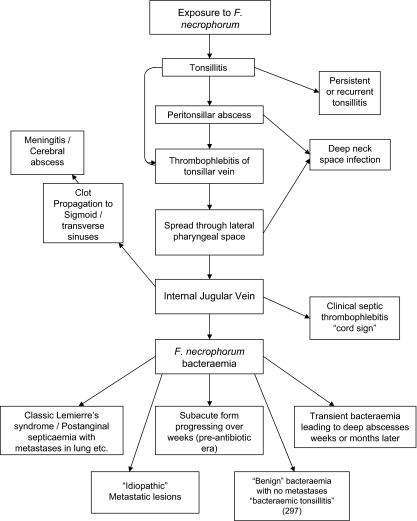

As stated before, the presence of Fusobacterium necrophorum is not requisite for a condition to be termed Lemierre’s Syndrome, therefore, there has been much controversy over the characteristics of a patient's condition that qualify them to fall under this classification. Similarly, exposure to the exogenous Fusobacterium necrophorum, which is also a part of normal throat flora does not always result in Lemierre’s syndrome; it can also result in tonsillitis, meningitis, and metastatic lesions, and a whole host of other issues (Fig. 3)(Riordan 2007). It is currently not known why infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum only occasionally causes Lemierre’s Syndrome, and why it takes divergent pathways to different conditions instead of progressing in a linear manner from one symptom to another. For more information on these other complications of Fusobacterium necrophorum infection, visit the section of this page titled: Complications Associated with Lemierre’s Syndrome.

Lemierre’s syndrome is classically associated with the post-anginal sepsis with later metastases of the infection into the lungs. It is classified as a severe septicemic infection, and is also known as necrobacillosis (Dack 1940). It is classified as a septicemic infection due to the fact that it can be cultured from the blood; the infection will not remain in the lesions where it develops. The thrombophlebitis that is associated with this condition is also an extremely important factor in the classification of these symptoms of Lemierre’s syndrome. Most patients of Lemierre syndrome typically show symptoms of a high fever, neck pain, and pulmonary problems, the thrombosis of the jugular is depicted in figure 4 (Lu 2009). Some define Lemierre’s Syndrome as a complication arising from an oropharyngeal infection due to the accumulation and infection of Fusobacterium necrophorum within the infected tissue.

History of Lemierre’s Syndrome

Similarly, exposure to the exogenous Fusobacterium necrophorum, which is not a part of normal throat flora does not always result in Lemierre’s syndrome; it can also result in tonsillitis, meningitis, and metastatic lesions, and a whole host of other issues (Fig. 2) [1]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

The Relationship Fusobacterium necrophorum with Lemierre’ s Syndrome

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Complications Associated with Lemierre’s Syndrome

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Treatment for Lemierre’s Syndrome

Conclusion

References

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.