Maladies in Honey Bees and Resistance to Varroa Mites: Difference between revisions

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

Beekeepers have been hard at work trying to find solutions for the epidemic of DWV and its vector the <i>Varroa</i> mite<ref name=" epidemic ">[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9976 Wilfert, L., Et al., “Deformed wing virus is a recent global epidemic in honeybees driven by <i>Varroa</i> mites” SCIENCE, vol. 351, 6273 (2016):594-597.]</ref>. | Beekeepers have been hard at work trying to find solutions for the epidemic of DWV and its vector the <i>Varroa</i> mite<ref name=" epidemic ">[https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac9976 Wilfert, L., Et al., “Deformed wing virus is a recent global epidemic in honeybees driven by <i>Varroa</i> mites” SCIENCE, vol. 351, 6273 (2016):594-597.]</ref>. Over the years, several chemical treatments have been created, one of the most popular and accessible being formic acid. Formic acid is inexpensive, does not contaminate the honey, and usually does not affect adult bees<ref name=" formic acid ">[https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025892906393 Underwood, M.., Et al., “The effects of temperature efficacy against <i>Varroa destructor<i> (Acari: Varroidae), a parasite of <i>Apis mellifera</i> (Hymenoptera: Apidae)” Experimental & Applied Acarology, vol. 29,303 (2003).]</ref>. However, it is not a perfect solution. Formic acid can be known to harm bee brood and its efficacy can vary greatly based on treatment methods such as temperature at the time of treatment and placement of the formic acid. Additionally, arguably the most important problem with formic acid is that it is becoming less effective as <i>Varroa</i> mites have begun to gain resistance to it. | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 14:00, 7 December 2022

Introduction

Apiculture is a complex trade of raising honeybee colonies. One of the main challenges in this occupation is the many maladies that honeybees face. Throughout history, beekeepers have worked to solve the problems plaguing their bees. These solutions range from chemicals to selective breeding for bees that have a tolerance for specific parasites. One example of such maladies is the Varroa mite which can be treated with chemicals but there is a new influx of keepers choosing branches of honey bees that are hardier when it comes to dealing with mites. Learning about the maladies of bees and keeping up on the new treatments discovered is an essential step for all beekeepers new and experienced. This is because when a beekeeper treats their domesticated bees for a malady, they end up helping the surrounding community of other colonies as well as native populations. Many of these diseases and parasites are transferable from hive to hive and can be deadly if left untreated. Therefore, the correct handling of these issues can have a positive impact on the native populations[1].

Varroa destructor

Varroa destructor commonly known as the varroa mite is one of the biggest threats to the beekeeping world currently, affecting both the beekeeping economy and contributing to the rapid decline in beekeeping populations. It is a parasite and a disease vector and can be deadly to a hive[2].

The first reported case of Varroa was in the Asian Honeybee in 1904 and by 1963 it had made its way to Hong Kong[3]. From there it entered the international honeybee trade and spread around the world. Therefore when Varroa reached the European Honeybee, they did not have defenses against the parasite.

One of the most important things to know when treating the Varroa mite is its life cycle. This life cycle is split into two phases: reproductive and dispersal. At the beginning of the reproductive cycle, a female mite enters an uncapped brood cell containing honeybee larvae at the beginning of the pupae stage. Once the cell is capped, the mite will puncture a whole in the prepupae from which to feed from. While it was previously believed that the mites feed on the bee’s hemolymph, it has recently been discovered that they actually feed on the bee’s body fat[4]. The female mite then lays eggs around this feeding area. When the new mites emerge, they immediately mate with each other and therefore emerge from the cell fertilized. When the bee emerges from its cell, attached to it are the mother and daughter mites (the males often are often removed from the food source after fulfilling their duty of mating and therefore die before emergence). From there the mites continue to feed off of the adult bee and sometimes transfer to other bees until it is time to enter another cell and create the next generation[3].

Deformed Wing Virus

While the parasites themselves weaken bees greatly, another major problem they cause is virus transmission due to their transfer between bees. They acquire the pathogen by ingesting it through the fatty tissues that they feed off of. Then the mite will transfer onto a different bee and begin to feed off of it and introduce the pathogen. One of the know viruses that have a direct connection to Varroa is Deformed Wing Virus (DWV). DWV is an icosahedral virus containing a single positive-stranded RNA [5].

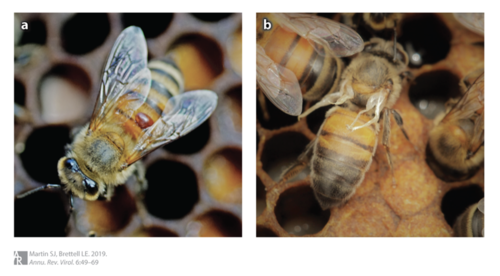

Symptoms of DWV include crumpled wings, smaller bodies, discoloration, and shortened life spans [1]. This virus is often found in correlation with Varroa mite infestations as, unlike other honey bee viruses, it moves slowly and allows the brood to continue to grow while infected. This allows the mites to develop on the growing brood and pass on the virus. And this virus is not uncommon. In French apiaries, the presence of DWV was found in 90% of hives and in 100% of Varroa mites[5]. Furthermore, it has been discovered that the DWV host range is broadening. It is now known to affect 65 known species from honeybee-like species such as bumblebees to arthropods and arachnids. Therefore, the problem caused by Varroa mites and the viruses they transmit has become a problem not just for domestic honeybees but for the broader ecological community [6].

Conclusion

Beekeepers have been hard at work trying to find solutions for the epidemic of DWV and its vector the Varroa mite[7]. Over the years, several chemical treatments have been created, one of the most popular and accessible being formic acid. Formic acid is inexpensive, does not contaminate the honey, and usually does not affect adult bees[8]. However, it is not a perfect solution. Formic acid can be known to harm bee brood and its efficacy can vary greatly based on treatment methods such as temperature at the time of treatment and placement of the formic acid. Additionally, arguably the most important problem with formic acid is that it is becoming less effective as Varroa mites have begun to gain resistance to it.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Chen, Y., Suede, R., “Honey bee viruses” Advances in virus research vol. 70 (2007): 33-80

- ↑ Doebler, Stefanie. "The Rise and The Fall of the Honeybee: Mite infestations challenge the bee and the beekeeping industry." BioScience vol. 50,9 (2000): 738-742.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Traynor, Kristen., et al., "Varroa destructor: A Complex Parasite Crippling Honey Bees World Wide." PNAS vol. 36,7 (2020): 593-606.

- ↑ Ramsey, Samuel. et al., “Varroa destructor feeds primarily on honeybee fat body tissue and not hemolymph” PNAS vol. 116,5 (2019): 1792-1801.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Lanzi, Gaetana, et al. “Molecular and biological characterization of deformed wing virus of honeybees (Apis mellifera L.).” Journal of virology vol. 80,10 (2006):4998-5009.

- ↑ Martin, Stephen J., and Laura E. Brettell. “Deformed Wing Virus in Honeybees and Other Insects.” Annual Review of Virology, vol. 6, no. 1, 2019, pp. 49–69.

- ↑ Wilfert, L., Et al., “Deformed wing virus is a recent global epidemic in honeybees driven by Varroa mites” SCIENCE, vol. 351, 6273 (2016):594-597.

- ↑ Underwood, M.., Et al., “The effects of temperature efficacy against Varroa destructor (Acari: Varroidae), a parasite of Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae)” Experimental & Applied Acarology, vol. 29,303 (2003).

Edited by Sarah Verner, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2022, Kenyon College.