Metallosphaera yellowstonensis: Difference between revisions

| (32 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

Archaea (Domain); | Archaea (Domain); TACK group "Crenarchaeota" (Superphylum); Thermoproteota (Phylum); Thermoprotei (Class); Sulfolobales (Order); Sulfolobaceae (Family); Metallosphaera (Genus) | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

This is a coccus-shaped chemolithoautotrophic archaea isolated from the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park (Kozubal et. al, 2008). ''M. yellowstonensis'' exists in Fe(II)-oxidizing microbial mats. Thermophilic chemolithoautotrophic acidophiles such as ''M. yellowstonensis'' have implications for understanding the evolutionary history of | This is a coccus-shaped chemolithoautotrophic archaea isolated from the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park (Kozubal et. al, 2008). ''M. yellowstonensis'' exists in Fe(II)-oxidizing microbial mats. Thermophilic chemolithoautotrophic acidophiles such as ''M. yellowstonensis'' have implications for understanding the evolutionary history of Earth, as well as insights into unique metabolic pathways existing in such extreme environments (Jennings et. al, 2014). The ability to survive in Fe (II)-oxidizing mats with minimal nutrient requirements other than inorganic compounds suggests an important role as a primary producer in these extreme environments (Kozubal et.al, 2008). | ||

[[File:41396 2013 Article BFismej2012132 Fig2 HTML.webp|caption]] | [[File:41396 2013 Article BFismej2012132 Fig2 HTML.webp|caption]] | ||

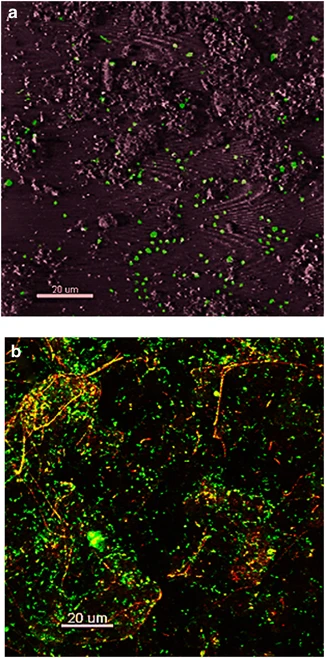

Images of confocal microscopy of Fe microbial mats (Kozubal | Images of confocal microscopy of Fe microbial mats (Kozubal et. al, 2013). (a) Thermoproteota-specific 16s rRNA FISH. (b) Mat stained with SYBR gold. | ||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

The genome of ''M. yellowstonensis'' is circular and large. In fact, it is the largest genome in the known ''Mettallosphaera'' genus at 2.82 Mb. Throughout the ''Mettallosphaera'' genus GC contents ranges from 42.0-50.4%. ( | The genome of ''M. yellowstonensis'' is circular and large. In fact, it is the largest genome in the known ''Mettallosphaera'' genus at 2.82 Mb. Throughout the ''Mettallosphaera'' genus GC contents ranges from 42.0-50.4%. (Wang et.al, 2020). Most genes throughout the genome average around 1kbp in length. Additionally, these genes tend to be adjacent to neighboring genes and separated by less than 200bp resulting in high density coding regions with minimal noncoding regions (Agustín, 2001). | ||

The prevalence of transposons in ''M. yellowstonensis'', ~283 transposon sequences per genome, likely provides extra functionality via horizontal gene transfer | From a genome annotation that was performed on ''M. yellowstonensis'' MK1 strain, 3,309 genes were identified in the genome, of these 2,907 were identified as encoding for protein, 48 as tRNA, 3 as rRNA [16s,23s, and 5s], and 349 genes as being pseudogenes (Gene, 2024). | ||

The prevalence of transposons in ''M. yellowstonensis'', ~283 transposon sequences per genome, likely provides extra functionality via horizontal gene transfer lending protection from the challenges of the hot spring environment. (Wang et.al, 2020) | |||

==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ||

''M. yellowstonesis'' can utilize different sulfur compounds (sulfide, elemental sulfur, thiosulfate) derived from | ''M. yellowstonesis'' can utilize different sulfur compounds (sulfide, elemental sulfur, thiosulfate) derived from hot springs and continental solfataras as an energy source. Additionally, ''M. yellowstonesis'' is capable of iron oxidation (''fox'' genes), and also posses an abundant amount of carbohydrate active enzymes that encode for: glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, archaeal pentose phosphate pathway, an atypical TCA cycle, and complete non-phosphative and semi phosphorylative entner doudoroff pathways (Wang et.al, 2020). | ||

Additionally, ''M. yellowstonesis'' has putative type I carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. ''M. yellowstonesis'' can also perform assimilatory nitrate reduction, with genes for nitrate and nitrite reductases. Unique from the rest of the genus, ''M. yellowstonensis'' MK1 also possesses an operon encoding for dissimilatory nitrate reductase. | Additionally, ''M. yellowstonesis'' has putative type I carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. ''M. yellowstonesis'' can also perform assimilatory nitrate reduction, with genes for nitrate and nitrite reductases. Unique from the rest of the genus, ''M. yellowstonensis'' MK1 also possesses an operon encoding for dissimilatory nitrate reductase (Wang et.al, 2020). | ||

[[File:GetImage.gif|caption]] | [[File:GetImage.gif|caption]] | ||

''M. yellowstonensis'' is found in microbial mats (acidic ferric iron mats), which are highly diverse communities that can provide an extreme environment with low pH, high temperatures, | Scanning electron micrographs of sulfur deposits from Yellow Stone hot spring (R. E. Macur et. al, 2004) | ||

==Ecology== | |||

''M. yellowstonensis'' is found in microbial mats (acidic ferric iron mats), which are highly diverse communities that can provide an extreme environment with low pH, high temperatures, nearly anaerobic conditions, and high concentrations of reduced iron (Kozubal et.al, 2008). Different organisms create the ribbons of color seen in the mats. In these mats millions of microbes can connect into long filaments, or thick sturdy structures coated by chemical precipitates (Thermophilic, 2020) | |||

''M. yellowstonensis'' produces EPS, which can be utilized in biofilm formation, and adhesion generally assisting in colonization, solubilizing minerals, and increased protection from the environment. It also maintains a unique flagellum composition and mode of assembly different from that of bacteria found in the crenarchael flagellin and accessory proteins (Wang et.al, 2020). | |||

''M. yellowstonensis'' has the ability to survive in natural/anthropogenic metal-rich environments. Unique from its genus, yellowstonensis possesses an alkylmercury lyase, which is important for mercury detoxification (Wang et.al, 2020). | |||

[[File:Microbial Mat.png|caption]] | [[File:Microbial Mat.png|caption]] | ||

Image of microbial mat (Boswell, 2007). | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

''Agustín Vioque, & Altman, S. (2001). Ribonuclease P. Elsevier EBooks, 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043408-7/50030-7'' | |||

'' | ''Gene - GCF_000243315.1. (2024). NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/gene/GCF_000243315.1/?gene_type=other'' | ||

| | ||

''Guy, L., & Thijs J.G. Ettema. (2011). The archaeal “TACK” superphylum and the origin of eukaryotes. Trends in Microbiology (Regular Ed.), 19(12), 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.002'' | |||

''Jennings, R. M., Whitmore, L. M., Moran, J. J., Kreuzer, H. W., & Inskeep, W. P. (2014). Carbon Dioxide Fixation by Metallosphaera yellowstonensis and Acidothermophilic Iron-Oxidizing Microbial Communities from Yellowstone National Park. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(9), 2665–2671. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.03416-13'' | |||

| | ||

''Kozubal, M., Macur, R. E., Korf, S., Taylor, W. P., Ackerman, G. G., Nagy, A., & Inskeep, W. P. (2008). Isolation and Distribution of a Novel Iron-Oxidizing Crenarchaeon from Acidic Geothermal Springs in Yellowstone National Park. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74(4), 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01200-07'' | |||

''Kozubal, M. A., Mensur Dlakic, Macur, R. E., & Inskeep, W. P. (2011). Terminal Oxidase Diversity and Function in “ Metallosphaera yellowstonensis ”: Gene Expression and Protein Modeling Suggest Mechanisms of Fe(II) Oxidation in the Sulfolobales. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(5), 1844–1853. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01646-10'' | |||

| | ||

''Macur, R. E., Langner, H. W., Kocar, B. D., & Inskeep, W. P. (2004). Linking geochemical processes with microbial community analysis: successional dynamics in an arsenic‐rich, acid‐sulphate‐chloride geothermal spring. Geobiology, 2(3), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4677.2004.00032.x'' | |||

''Metallosphaera yellowstonensis MK1 MetMK1scaffold_10, whole genome sho - Nucleotide - NCBI. (2024). Nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_JH597761'' | |||

'' | ''Summary of Metallosphaera yellowstonensis MK1, version 28.0. (2022). Biocyc.org. https://biocyc.org/GCF_000243315/organism-summary'' | ||

''taxonomy. (2020). Taxonomy browser (Metallosphaera yellowstonensis). Nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Undef&id=1111107&lvl=3&lin=s&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock&log_op=lineage_toggle'' | |||

https://www. | |||

''Thermophilic Communities - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service). (2020). Nps.gov. https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/thermophilic-communities.htm'' | |||

''Wang, P., Liang Zhi Li, Ya Ling Qin, Zong Lin Liang, Xiu Tong Li, Hua Qun Yin, Li Jun Liu, Liu, S.-J., & Jiang, C.-Y. (2020). Comparative Genomic Analysis Reveals the Metabolism and Evolution of the Thermophilic Archaeal Genus Metallosphaera. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01192'' | |||

https:// | |||

| |||

''Boswell, Evelyn (2007). New bacterium found in microbial mats of Yellowstone. MSU news service. https://www.montana.edu/news/4997'' | |||

| | ||

==Author== | ==Author== | ||

Page authored by | Page authored by Hannah Markley and Anna Tieman, students of Prof. Jay Lennon at IndianaUniversity. | ||

<!-- Do not remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Jay Lennon at Indiana University]] | <!-- Do not remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Jay Lennon at Indiana University]] | ||

Latest revision as of 12:01, 25 April 2024

Classification

Archaea (Domain); TACK group "Crenarchaeota" (Superphylum); Thermoproteota (Phylum); Thermoprotei (Class); Sulfolobales (Order); Sulfolobaceae (Family); Metallosphaera (Genus)

Species

|

NCBI: [1] |

Description and Significance

This is a coccus-shaped chemolithoautotrophic archaea isolated from the hot springs of Yellowstone National Park (Kozubal et. al, 2008). M. yellowstonensis exists in Fe(II)-oxidizing microbial mats. Thermophilic chemolithoautotrophic acidophiles such as M. yellowstonensis have implications for understanding the evolutionary history of Earth, as well as insights into unique metabolic pathways existing in such extreme environments (Jennings et. al, 2014). The ability to survive in Fe (II)-oxidizing mats with minimal nutrient requirements other than inorganic compounds suggests an important role as a primary producer in these extreme environments (Kozubal et.al, 2008).

Images of confocal microscopy of Fe microbial mats (Kozubal et. al, 2013). (a) Thermoproteota-specific 16s rRNA FISH. (b) Mat stained with SYBR gold.

Genome Structure

The genome of M. yellowstonensis is circular and large. In fact, it is the largest genome in the known Mettallosphaera genus at 2.82 Mb. Throughout the Mettallosphaera genus GC contents ranges from 42.0-50.4%. (Wang et.al, 2020). Most genes throughout the genome average around 1kbp in length. Additionally, these genes tend to be adjacent to neighboring genes and separated by less than 200bp resulting in high density coding regions with minimal noncoding regions (Agustín, 2001).

From a genome annotation that was performed on M. yellowstonensis MK1 strain, 3,309 genes were identified in the genome, of these 2,907 were identified as encoding for protein, 48 as tRNA, 3 as rRNA [16s,23s, and 5s], and 349 genes as being pseudogenes (Gene, 2024).

The prevalence of transposons in M. yellowstonensis, ~283 transposon sequences per genome, likely provides extra functionality via horizontal gene transfer lending protection from the challenges of the hot spring environment. (Wang et.al, 2020)

Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle

M. yellowstonesis can utilize different sulfur compounds (sulfide, elemental sulfur, thiosulfate) derived from hot springs and continental solfataras as an energy source. Additionally, M. yellowstonesis is capable of iron oxidation (fox genes), and also posses an abundant amount of carbohydrate active enzymes that encode for: glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, archaeal pentose phosphate pathway, an atypical TCA cycle, and complete non-phosphative and semi phosphorylative entner doudoroff pathways (Wang et.al, 2020).

Additionally, M. yellowstonesis has putative type I carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. M. yellowstonesis can also perform assimilatory nitrate reduction, with genes for nitrate and nitrite reductases. Unique from the rest of the genus, M. yellowstonensis MK1 also possesses an operon encoding for dissimilatory nitrate reductase (Wang et.al, 2020).

Scanning electron micrographs of sulfur deposits from Yellow Stone hot spring (R. E. Macur et. al, 2004)

Ecology

M. yellowstonensis is found in microbial mats (acidic ferric iron mats), which are highly diverse communities that can provide an extreme environment with low pH, high temperatures, nearly anaerobic conditions, and high concentrations of reduced iron (Kozubal et.al, 2008). Different organisms create the ribbons of color seen in the mats. In these mats millions of microbes can connect into long filaments, or thick sturdy structures coated by chemical precipitates (Thermophilic, 2020) M. yellowstonensis produces EPS, which can be utilized in biofilm formation, and adhesion generally assisting in colonization, solubilizing minerals, and increased protection from the environment. It also maintains a unique flagellum composition and mode of assembly different from that of bacteria found in the crenarchael flagellin and accessory proteins (Wang et.al, 2020).

M. yellowstonensis has the ability to survive in natural/anthropogenic metal-rich environments. Unique from its genus, yellowstonensis possesses an alkylmercury lyase, which is important for mercury detoxification (Wang et.al, 2020).

Image of microbial mat (Boswell, 2007).

References

Agustín Vioque, & Altman, S. (2001). Ribonuclease P. Elsevier EBooks, 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-008043408-7/50030-7

Gene - GCF_000243315.1. (2024). NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/gene/GCF_000243315.1/?gene_type=other

Guy, L., & Thijs J.G. Ettema. (2011). The archaeal “TACK” superphylum and the origin of eukaryotes. Trends in Microbiology (Regular Ed.), 19(12), 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.002

Jennings, R. M., Whitmore, L. M., Moran, J. J., Kreuzer, H. W., & Inskeep, W. P. (2014). Carbon Dioxide Fixation by Metallosphaera yellowstonensis and Acidothermophilic Iron-Oxidizing Microbial Communities from Yellowstone National Park. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 80(9), 2665–2671. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.03416-13

Kozubal, M., Macur, R. E., Korf, S., Taylor, W. P., Ackerman, G. G., Nagy, A., & Inskeep, W. P. (2008). Isolation and Distribution of a Novel Iron-Oxidizing Crenarchaeon from Acidic Geothermal Springs in Yellowstone National Park. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 74(4), 942–949. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01200-07

Kozubal, M. A., Mensur Dlakic, Macur, R. E., & Inskeep, W. P. (2011). Terminal Oxidase Diversity and Function in “ Metallosphaera yellowstonensis ”: Gene Expression and Protein Modeling Suggest Mechanisms of Fe(II) Oxidation in the Sulfolobales. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 77(5), 1844–1853. https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.01646-10

Macur, R. E., Langner, H. W., Kocar, B. D., & Inskeep, W. P. (2004). Linking geochemical processes with microbial community analysis: successional dynamics in an arsenic‐rich, acid‐sulphate‐chloride geothermal spring. Geobiology, 2(3), 163–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4677.2004.00032.x

Metallosphaera yellowstonensis MK1 MetMK1scaffold_10, whole genome sho - Nucleotide - NCBI. (2024). Nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/NZ_JH597761

Summary of Metallosphaera yellowstonensis MK1, version 28.0. (2022). Biocyc.org. https://biocyc.org/GCF_000243315/organism-summary

taxonomy. (2020). Taxonomy browser (Metallosphaera yellowstonensis). Nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Undef&id=1111107&lvl=3&lin=s&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock&log_op=lineage_toggle

Thermophilic Communities - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service). (2020). Nps.gov. https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/thermophilic-communities.htm

Wang, P., Liang Zhi Li, Ya Ling Qin, Zong Lin Liang, Xiu Tong Li, Hua Qun Yin, Li Jun Liu, Liu, S.-J., & Jiang, C.-Y. (2020). Comparative Genomic Analysis Reveals the Metabolism and Evolution of the Thermophilic Archaeal Genus Metallosphaera. Frontiers in Microbiology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01192

Boswell, Evelyn (2007). New bacterium found in microbial mats of Yellowstone. MSU news service. https://www.montana.edu/news/4997

Author

Page authored by Hannah Markley and Anna Tieman, students of Prof. Jay Lennon at IndianaUniversity.