Microbes in Agricultural Soil: Difference between revisions

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

[[Image:Microbial interactions.webp|thumb| | [[Image:Microbial interactions.webp|thumb|600px|right|Microbial interactions across different soil compartments. There is a large amount of microbial diversity in the rhizosphere, yet when compared to bulk soil the interactions are relatively simple. In nodules, the portion of the plant involved in symbiosis, the microbial network complexity declined, bu the correlation among the bacteria increased. See “Variation in rhizosphere microbial communities and its association with the symbiotic efficiency of rhizobia in soybean” from Han et al. for more information. Photo credit: <ref name= han> [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41396-020-0648-9/ Han et al. “Variation in rhizosphere microbial communities and its association with the symbiotic efficiency of rhizobia in soybean.” 2020. <i> The ISME journal</i> 14(8):1915-1928.] </ref>]] | ||

===Mycorrhizal fungi=== | ===Mycorrhizal fungi=== | ||

Latest revision as of 02:23, 15 April 2024

Microbes within Agricultural Soils

By Claire Epperson

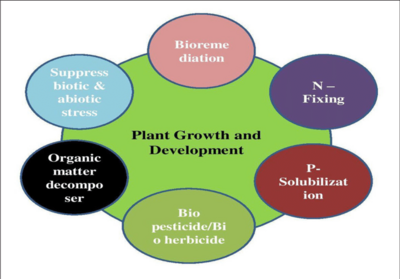

Microbes can be found across a variety of environments, including in the soils. In fact, it has been said that there are more microbes in a teaspoon of soil than there are people on Earth [2]. These microbes serve a multitude of ecosystem functions. Soil microbes are beneficial in determining the nutrient content of food, and this is often done through the transformation of degradable organic compounds to an inorganic, readily available form for crops [3]. Some examples of these microbes include Bacillus, Azotobacter, Microbacterium, Erwinia, Beijerinckia, Enterobacter, Flavobacterium, Pseudomonas, and Rhizobium bacteria, which are all examples of phosphate solubilizers [3]. A phosphate solubilizer turns phosphate, a crucial nutrient, from an inaccessible form to one that is easily taken in and stored by plants. Some other examples include cyanobacteria (Anabaena, Nostoc, Calothrix), Azotobacter, Azospirillum, and Gluconacetobacter, which are nitrogen-fixing endophytes, a type of symbiote [3]. Similar to phosphate solubilizers, nitrogen-fixers convert nitrogen to a form more easily accessible to plants. Many farmers have even turned to the application of microbes to promote and maintain soil health [3]. In addition to microorganisms, earthworms also play a role in soil health. Both microorganisms and earthworms leave castings, the end product of digestion, and residuals that serve to increase plant nutrients [4]. When compared to soil devoid of these, soil that had been shaped by microorganism and earthworm activity showed a significant increase in nutrient levels [4]. The presence and activity of such organisms is crucial not just for plant health but also human and animal health.

The abundance and diversity of species as well as their activity vary drastically depending on the soil environment. The optimal environment for soil organisms is that of a natural and healthy soil, in which the biomass of microbes can amount to 4 to 5 tonnes per hectare [4]. However, soil health and fertility is declining in places as a result of increasing fertilizer use, tillage, and crop protectants [4]. As a result of the soil disruption, populations of soil organisms are subject to decline. Many farmers have begun utilizing sustainable farming techniques that limit fertilizer and soil disruption as well as actively introducing healthy microbes to the soil.

Soil organic Matter

One of the most nutrient rich portions of soil is the soil organic matter (SOM). Not only is SOM beneficial for microbes, but it also acts as a buffer for high acidity and increases water availability within the soil, acting as a sponge and releasing it for plant use [5]. Furthermore, SOM helps decompose excess pesticides and acts as a carbon sink, sequestering atmospheric carbon [6],[5] . SOM is composed of organic substances (those with carbon) in the soil. This includes plants, algae, microorganisms, and decomposing matter left from both plants and microorganisms [2].

The three main components of the SOM are the “living” (microorganisms), the “dead” (fresh residue) and the “very dead” (humus- long decomposed plant and animal substances) [2],[5] . These components are then broken down into further classification. The SOM is composed of active (35%) and passive (65%) [2]. Active SOM consists of the “living” and “dead” plant and animal materials. These are composed of easily digested sugars and proteins, acting and food for the microbes within the soil [2]. The active layer contains the microbes that convert nutrients into a form more readily available for plants The passive SOM is unable to be decomposed by microbes and is higher in lignin [2]. Passive SOM is the portion that acts as a carbon sink.

Symbiosis

Many of the benefits of soil microbes, including the conversion of nutrients into a readily available form, are a result of a symbiotic relationship. One example is the relationship between the hyphae of soil fungus and plants. The fungi possess a root-like structure, hyphae, that forms a network of structure that helps soil particles bind together, thereby improving both the stability and the structure of the soil for plants [4]. This is not the only example of symbiotic relationship within the soil, many of which involve essential soil microbes.

Mycorrhizal fungi

Another example of a symbiotic relationship within the soil results in nitrogen fixation. Nitrogen fixation is a crucial process that is essential for life and is carried out primarily by nitrogen-fixing bacteria and archaea within the soil [7]. However, this process would not be possible within the symbiotic relationship between soil microbes and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi are also beneficial in getting nutrients to plants. Nitrogen fixing-bacteria and phosphate-solubilizing bacteria work with the mycorrhizal fungi to increase nutrient availability for plants. The bacteria fix the nitrogen, converting it from molecular form to a usable form like ammonia, as well as solubilize phosphorus ions, making them more soluble for plant uptake [3]. Finally, the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which are spread through the soil, transport these nutrients directly to the plants [3]. Without this symbiotic relationship, plant nutrient uptake would not be as successful

Rhizosphere

Similar to the SOM, the rhizosphere is a crucial component of the soil, serving as the nutrient-rich portion surrounding the plant roots. A variety of symbiotic relationships within this portion of the soil aids in plant health. In fact, the aforementioned mycorrhizal fungi extended from within the rhizosphere and throughout the bulk soil. Microbial activity within the rhizosphere performs a number of activities including nitrogen-fixation, nutrient solubilization, suppression of pests and pathogens, tolerance of plant stress, decomposition of organic residue, and the recycling of soil nutrients [8]. Microbes in the rhizosphere establish a number of symbiotic relationships with host plants, including beneficial (like arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi), neutral, and detrimental [3], [8]. The symbiotic relationship between rhizobia and legumes is a mutualistic form of symbiosis, benefitting both [7]. Rhizobia, a type of nitrogen-fixing bacteria, can live in the soil on decaying matter or on the root nodules of their host legumes as a symbiont [7]. The rhizobia fix atmospheric nitrogen for their host, converting it to a usable form, while the host supplies rhizobia with the carbon from photosynthesis [7]. Though this is one example of many, the microbes within the soil are crucial components in promoting plant growth. Unfortunately, the microbes are susceptible to disturbance in response to aggressive environmental conditions and farming practices.

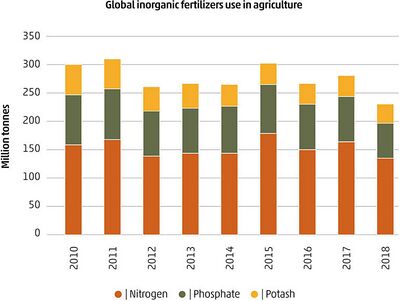

Pollution in Agricultural Soils

One of the threats to a healthy soil microbiome is the multitude of contaminates that are being introduced to the soil. The main sources of pollution to agricultural soils are pesticides, mineral fertilizers, organic fertilizers (manure and sewer sludge), wastewater, plastic material (greenhouses and irrigation tubes), and rural waste [9] . A side effect of these pollutants is a build up of heavy metals. One such metal is cadmium. Cadmium accumulation is widespread as a result of advanced technology, particularly rapid increases in development during the industrial revolution [10]. Cadmium is very mobile in the soil and results in high toxicity, inhibiting the positive side effects of microbes within the soil [10]. This includes inhibiting microbial growth and metabolic processes, a similar side effect to lead accumulation [10]. In addition to heavy metals, one of the most widespread and debilitating sources of pollution in agricultural soils is the overapplication of fertilizers. Overuse of nitrogen fertilizer results in nitrogen loss from the soil through volatilization, denitrification, leaching into groundwater, and through surface runoff and erosion [9]. Furthermore, microbial activity transforms nitrogen into nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas responsible for global warming; excess nitrogen in the soil results in excess nitrous oxide being emitted [9]. Organic fertilizer can also cause detrimental impacts when used in excess. While biosolids have been tested as approved for use as fertilizers, septic sludge, containing potential harmful microbes, has not [9]. Following the use of organic fertilizers, whether from human or animal origin, there is the possibility of an increase in antimicrobials and antimicrobial resistant organisms [9]. Antimicrobials are often used in agriculture on a routine basis in the hopes of preventing disease and promoting growth. Unfortunately, it is reported that between 75% to 90% of administered antimicrobials are not completely metabolized, meaning these antimicrobials can accumulate in wastewater, manure, and biosolids [9]. When these are used as organic fertilizers, antimicrobials can be directly placed in agricultural soils. Antimicrobials, even at low levels, can result in the spread of antimicrobial-resistant microbes and the spread of antimicrobial resistant genes (ARGs) throughout the microbes within the soil [9]. Overall, pollution within agricultural soil acts as a threat not only to plant health and growth, but can also pose harm for human health. Fortunately, innovations have emerged that seek to control the microbial community within the soil.

Sustainable Farming

When farming, not only is it important to consider plant health but also soil health. Natural soil processes regenerate soil over time, but the rate of formation is slow [11]. In order to best conserve soil, many have begun to consider it a nonrenewable resource. As a result, there is been a movement for sustainable agriculture, a method that provides the most beneficial services for agroecosystems and emphasizes the long-term, rather than short term and often detrimental, production of food supplies [11]. A number of farming methods have been encouraged that not only conserve soil, but regenerate it, reintroducing the microbes and nutrients within.

Sustainable Practices

Many agricultural practices following the industrial revolution become extractive, drawing out nutrients without replenishing them. Agricultural processes of planting and harvesting alter nutrient cycling within the soil. Generally, SOM, the nutrient rich portion of soil and vital for bacterial and plant health, is highest in areas where disturbance to soil is minimized [5]. Intensive cultivation and crop harvesting for humans and animals mine soil nutrients away from plants [11]. As a result, soil amendments are being used to maintain fertility and crop yields. Unfortunately, some amendments are used in excess and instead serve the opposite of their intended function. For example, using 80kg/ha of nitrogen fertilizer can reduce soil microbial populations by 25%, and phosphorus rich fertilizers can reduce the positive effects of mycorrhizal fungi [4]. Furthermore, high nitrogen levels can also reduce humus levels, the substance in the passive portion of the SOM responsible for increasing water holding capacity. One study found that “for every 1kg of excess Nitrogen applied, 100kg of soil humus is destroyed” [4]. One way to offset the negative consequences of overuse of fertilizers and pesticides is to use bio alternatives.

Microbial Management

Microbial bioalternatives have been used in sustainable agriculture, including biofertilizers, biopesticides, bioherbicides, and bioinsecticides among others [3]. Biofertilizers, for example, improve aquatic holding capacity, carbon storage, root growth, availability and cycling of essential nutrients, as well as filtering pollutants [3]. The use of microbial management is a growing field, taking care not just of crops but of soil and the microbes within.

Microbial Addition

The goal of microbial addition is to increase the overall number of beneficial microbes in the soil, introduce specific microbes to aid a specific crop, or introduce specific microbes that can increase nutrient ability [12]. Increasing nutrient availability can be done via biofertilizers and biostimulants, pest suppression can be achieved via biopesticides, and the stimulation of plant growth can be achieved via hormone signaling through the use of plant growth promoters or biostimulants [3],[12]. Using commercial products can add microbes targeted for specific functions, [12]. One such commercial product seeks to enhance the aforementioned symbiotic relationships, inoculation with rhizobia being the most common and well-researched [12]. There are also products that increase symbiosis via the inoculation of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. These products typically contain the species Glomus [12]. Microbial addition can also be done with on-farm microbial mixtures for a less targeted approach. These mixtures, often compost or manure, generally contain microbes that are unknown to the farmer. The mixture can contain the beneficial microbes, acting as biofertilizers and biopesticides, but they might also contain pathogens that might not be beneficial to the soil or crop [12]. Microbes get into soils constantly and naturally via dust, animals, and rain, but when microbial communities become too harmful to the soil or plants, some farmers opt to rid the soil of them entirely.

Microbial Suppression

When pathogenic microbes within the soil become rampant and harmful, outcompeting the beneficial microbes and posing threats to crops and human health, some farmers mitigate the consequences the blanket approaches that reset the microbial communities within the soil. Certain microbial pathogens can result in total crop failure, and the aforementioned approaches seek to rid the soil not only of these microbes but also neutral and beneficial ones as well [12]. Non sustainable agriculture might approach blanket eradication through the use of chemical pesticides or even soil fumigation [12]. Another, more organic form of suppression is called anaerobic soil disinfestation (ASD). This method uses large quantities of organic matter covered in a tarp, forming anaerobic conditions and allowing the microorganisms to degrade [13]. As previously mentioned, the use of pesticides harms the ability of soils to retain not only microbes but also important nutrients [4]. However, microbes that were killed off release resources that are quickly taken up by incoming microbes, such as those brought in naturally via dust, rain, or animals [12]. Microbes can quickly repopulate the now cleared soil within days or weeks. One such microbe is Bacillus, using location to quickly travel through soil that is sufficiently saturated [12]. Due to the aggressive nature of the treatment, some farmers follow microbial suppression with microbial addition, using compost or other sources of beneficial bacteria. Once these beneficial microbes are established, they are better able to outcompete the more harmful, pathogenic ones, as they have already taken available space and resources [12]. Once the beneficial microbes return, the associated benefits quickly follow.

Soil Health and Human Health

Microbes serve a number of functions beneficial not only to soil health, but also to human health. They are essential for processes including “crop fertility, purifying the environment from pollutants, regulating carbon storage stocks and production and consumption of many significant green house gasses, such as methane and nitrous oxide” [6] . One such benefit is the purification of the environment.

Reduction of Pathogens and Pollutants

Bacteria are the most abundant type of organism in the soil, being found in every soil on Earth [14]. Though most organisms in the soil do not pose a threat to humans, soil provides a home to organisms that can be pathogenic. One such organism is a protozoa, a single-celled eukaryote. While most in the soil feed on bacteria and algae, some can cause human parasitic disease such as diarrhea and dysentery [14]. One of the ways pathogenic viruses can enter soil is through human septic and sewage waste [14]. Soil contamination does not just occur in rural areas, occurring in both farming and urban areas. This contamination contains a mixture of organic chemicals, metals, and microorganisms caused by municipal and domestic septic system waste, farm animal waste, and other biowastes [14]. This can lead to the previously mentioned spread of ARGs, which have the potential for further spread and pose a threat to human health [9]. However, one of the benefits of soil microbes is the ability to filter potential pollutants. Both minerals and microbes can “filter, buffer, degrade, immobilize, and detoxify organic and inorganic materials,” and this includes the aforementioned industrial and municipal by-products as well as deposits from the atmosphere [15]. Microbes not only serve to benefit plant health but also mitigate some of the contaminates that pose threats to human health.

Crop Fertility and Nutrients

In regards to agricultural benefits, microorganisms can aid in crop fertility. Exogenous phytase addition has been used to enhance mineral bioavailability, and phytase-producing microbes in general have provided the possibility for the nutritional application for human food and animal feed [3]. Microbes play a role in the hopes of meeting projected food needs and diminishing food insecurity. Food production and quality include not only the production of food (tied closely with healthy agricultural soils) but also adequate nutrient content within the food products and the exclusion of toxic compounds [14]. Soil is important in meeting all the previously mentioned requirements. Soils that provide adequate nutrients for plants result in crops with more nutrient-rich tissues that, when consumed, contain the elements needed for human life [14].

Implications for the Future

Microbes are incredibly important for soil productivity, but there is still much left unknown about microbial soil communities and their functions. Unfortunately, this means that concrete predictions are hard to assume for microbes in the face of climate change. Not only are microorganisms influenced by the changing climate, but they can also play a part in mitigation, as they perform carbon and nutrient cycling [16],[17],[18]. The future of microbial activity rests largely in how resilience microbes are to stress conditions following climate change.

Climate change

One of the biggest threats following climate change is a rising temperature. The impact of rising temperatures have been studied across different environments, but some of the most susceptible areas are those in colder climates. In regards to the permafrost located at the poles, roughly 5-15% of the carbon within is susceptible to microbial decomposition, resulting in carbon dioxide emissions and further climate degradation [16] . In terms of agricultural ecosystems, grasslands have been used for cultivation and grazing, comprise about 26% of land areas (70% of agricultural area) and store an estimated 20% of the carbon stock [16]. Vulnerability of these ecosystems is closely linked to the symbiotic interactions within the rhizosphere [16]. One of the consequences of climate change and rising temperature is drought. These conditions threaten plant carbohydrate exchange and nutrient uptake in the rhizosphere by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, as AMF cannot colonize under drought conditions [18]]. In order to counteract the negative side effects of drought, plant stress tolerance needs to improve to allow production of crops under limited water availability [17],[18]. Plant growth promoting (PCP) bacteria and the fungi within the rhizosphere might counteract the consequences of drought by optimizing plant growth following stressful conditions [16],[10]. Increasing plant growth and development also helps reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide by increasing carbon sequestration [3],[7],[10]. This is not the only benefit soil microbes have on mitigating the negative effects of climate change, particularly drought. Some soil bacteria can produce extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) which creates hydrophobic biofilms that provide plants protection against water loss [10]. EPS not only protects plants from water loss, but can also retain water in the soil, making it more accessible for roots [17],[18],[10].. In combination with EPS, species of Bacillus in the rhizosphere produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), which can stimulate root development [10]. The increase in root biomass and length aid both in water retention and uptake, reducing stress and even having the potential to create soil organic matter [10]. Despite the potentially devastating impact of a changing climate, microbes within the soil have the potential to mitigate consequences, making crops within agricultural soils more resilient.

Conclusion

Microbes within the soil are vital contributors to ecosystem functions, contributing to nutrient cycling, plant growth, and mitigating pathogenic spread among many other benefits. In agricultural soils specifically, the number of symbiotic relationships between plants and bacteria increases plant productivity and helps meet current food demands. Unfortunately, pollution from multiple sources poses threats to human health and crop production. The microbes within the soil mitigate not just threats to flora but also to humans. Sustainable agricultural methods seek to not only produce nutrient-rich foods but also nutrient rich soils, and methods have emerged that seek to farm microbes along with the crops. In the near future, climate change poses an unknown threat to microbes in the soil. Evidence suggests that microbes have a level of resiliency to change, something that is enhanced and shared through symbiotic interactions with plants and crops.

References

- ↑ [https://agsolutions.com.au/soil-microbes-sustainability/ “Soil Microbes For Sustainable Farming” AgSolutions

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Hoorman, J and Islam, R. "Understanding Soil Microbes and Nutrient Recycling." 2010. Agriculture and Natural Resources.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Suman et al. “Microbiome as a key player in sustainable agriculture and human health.” 2022. Frontiers in Soil Science 2:821589.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 “Soil Microbes For Sustainable Farming” AgSolutions

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 [https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/sites/default/files/2022-10/Soil%20Organic%20Matter.pdf “Soil Organic Matter” (2014) Natural Resources Conservation Service

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 “Why do soil microbes matter?” UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Han et al. “Variation in rhizosphere microbial communities and its association with the symbiotic efficiency of rhizobia in soybean.” 2020. The ISME journal 14(8):1915-1928.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 “What are Soil Microbes? And Why Do They Matter in Agriculture?” Locus Agriculture

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 “Sources of soil pollution and major contaminants in agricultural areas” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Kumari et al. “Soil microbes: a natural solution for mitigating the impact of climate change” (2023) Environ Monit Assess 195:1436

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Parikh, S. J. & James, B. R. “Soil: The Foundation of Agriculture” (2012) Nature Education Knowledge 3(10):2

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 Isbell et al. “Management of Soil Microbes on Organic Farms” (2021) eOrganic

- ↑ [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780444525123001777 Lazarovits, G., A. Turnbull, and D. Johnston-Monje. "Plant health management: biological control of plant pathogens." (2014): Encyclopedia of Agriculture and Food Systems 388-399.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Brevik, E. C. and Burgess, L. C. “The Influence of Soils on Human Health” (2014) Nature Education Knowledge 5(12):1

- ↑ [https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/conservation-basics/natural-resource-concerns/soils/soil-health “Soil Health” Natural Resources Conservation Service

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Jansson, J.K. and Hofmockel, K.S“Soil microbiomes and climate change”. (2020) Nat Rev Microbiol 18:35–46

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Dubey et al. “Soil microbiome: a key player for conservation of soil health under changing climate.” (2019) Biodivers Conserv 28:2405–2429

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 [doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.899464. Afridi et al. “New opportunities in plant microbiome engineering for increasing agricultural sustainability under stressful conditions.” (2022) Front Plant Sci. 13:899464]

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski,at Kenyon College,2024