R. gnavus: Difference between revisions

| (40 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | {{Uncurated}} | ||

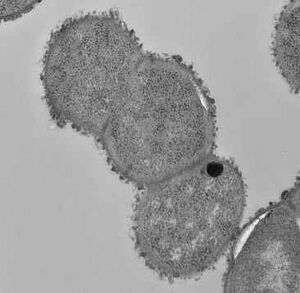

[[Image: | [[Image:R.gnavus1.jpg|thumb|300px|right| (<i>Ruminococcus gnavus imaging via microscope</i>). Image credit: National Institutes of Health.]] | ||

==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

Bacteria (Domain); Bacillota (Phylum); Clostridia (Class); Eubacteriales (Order); Lachnospiraceae (Family); Mediterraneibacter (Genus) | Bacteria (Domain); Bacillota (Phylum); Clostridia (Class); Eubacteriales (Order); Lachnospiraceae (Family); Mediterraneibacter (Genus) | ||

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=33038 | |||

===Species=== | ===Species=== | ||

| Line 10: | Line 12: | ||

| height="10" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | | | height="10" bgcolor="#FFFFFF" | | ||

''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' | ''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' | ||

==Description and Significance== | ==Description and Significance== | ||

''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' is a Gram-positive obligate anaerobe bacterium discovered first in the human gastrointestinal tract. Despite its name it is actually a part of the genus Mediterraneibacter, although retaining its Ruminococcus name for study purposes. | Discovered in 1974,''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' is a Gram-positive obligate anaerobe bacterium discovered first in the human gastrointestinal tract. Despite its name it is actually a part of the genus Mediterraneibacter, although retaining its Ruminococcus name for study purposes. | ||

''<i>R.gnavus</i>'' is considered a part of the normal human gut microbiome in children and adults. It has been suggested that it has a role in priming the gut microbiota in association with standard weight gain velocity in infants. | ''<i>R.gnavus</i>'' is considered a part of the normal human gut microbiome in children and adults. It has been suggested that it has a role in priming the gut microbiota in association with standard weight gain velocity in infants. ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' has also been linked to disease, as an overabundance of "<i>R. gnavus</i>" in the gut is associated with the exacerbation of symptoms of Crohn’s disease such as abdominal pain and diarrhea (4). | ||

''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' is one of few | ''<i>Ruminococcus gnavus</i>'' is one of few microbiota bacterium that persists at a consistent level from infancy to throughout adulthood. Studies have shown that ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' is a key biomarker of health and diseases with certain immune/metabolic properties, making it an important bacterium to understand. | ||

==Genome Structure== | ==Genome Structure== | ||

''Ruminococcus gnavus'' contains circular chromosomes containing 77 RNA coding genes, 3345 protein coding genes, and 3549191 nucleotides. | ''Ruminococcus gnavus'' contains circular chromosomes containing 77 RNA coding genes, 3345 protein coding genes, and 3549191 nucleotides. | ||

''R.gnavus'' was found to have a mean genome size of 3.46±0.34 Mbp, with a mean G+C conctent of 42.73±0.33 mol%. | ''R.gnavus'' was found to have a mean genome size of 3.46±0.34 Mbp, with a mean G+C conctent of 42.73±0.33 mol%. ''R.gnavus''' pan-core genome analysis revealed a predicted 28,072 genes, with the core genes making up 3.74% (1051) of that. Strain ATCC 29149 of ''R. gnavus'' was used for initial classification of this species into the Ruminococcus genus. The genome of strain ATCC 29149 consists of 43% G:C, which is similar to that of other species within the genus Ruminococcus (2). The genome size of strain ATCC 29149 was 3.62 Mb (1). | ||

''R.gnavus''' pan-core genome analysis revealed a predicted 28,072 genes, with the core genes making up 3.74% (1051) of that. | |||

Strain ATCC 29149 of ''R. gnavus'' was used for initial classification of this species into the Ruminococcus genus. The genome of strain ATCC 29149 consists of 43% G:C, which is similar to that of other species within the genus Ruminococcus ( | |||

==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ==Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life Cycle== | ||

[[Image:R.gnavus2.webp|thumb|300px|right| (<i>Ruminococcus gnavus cluster via microscope</i>). Image credit: The Quadrum Institute.]] | |||

Ruminococcus are coccoid shaped and have not been found to produce spores ( | Ruminococcus are coccoid shaped and have not been found to produce spores (1). They can be motile or nonmotile and possess one to three flagella (2). Visually, the cells are elongated with ends that taper off. The usual dimensions of the cell are 0.9 to 1.1 picometers by 1.1 to 1.4 picometers (2). | ||

''R. gnavus'' was initially classified into the Ruminococcus genus due to its high levels of growth on fermentable carbohydrates. The microbe is now considered to be anaerobic, experimentally demonstrating little tolerance to oxygen after exposure ( | ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' was initially classified into the Ruminococcus genus due to its high levels of growth on fermentable carbohydrates. The microbe is now considered to be anaerobic, experimentally demonstrating little tolerance to oxygen after exposure (5). ''<i>R. gnavus</i>''uses fermentation to produce energy, acetate, and formate (3). Other metabolites of ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' include ethanol and lactate. The ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' strain ATCC 29149 breaks down mucin glycan, a carbohydrate component of the mucus lining of the gut, along with glycans that come from dietary sources (3). Studies have also shown that ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'' can use substances produced by ''<i>R. bromii</i>'', such as glucose and malto-oligosaccharides, as food and energy sources (6). Secondary metabolites of ''<i>R. gnavus</i>'', including tryptophan decarboxylase, have also been identified in mice models (3). | ||

==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ==Ecology and Pathogenesis== | ||

There are a multitude of studies that show a large positive association between Crohn's disease and ''Ruminococcus gnavus'' populations. ''R. gnavus'' populations skyrocket during flare ups in Crohn's disease patients. ''R. gnavus'' produces an inflammatory glucorhamnan polysaccharide that triggers the production of inflammatory cytokines. | There are a multitude of studies that show a large positive association between Crohn's disease and ''Ruminococcus gnavus'' populations. ''R. gnavus'' populations skyrocket during flare ups in Crohn's disease patients. ''R. gnavus'' produces an inflammatory glucorhamnan polysaccharide that triggers the production of inflammatory cytokines. ''R. gnavus'' may increase oxidative stress, which is often present in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (8). | ||

Patients experiencing Crohn's disease and an increase in ''R. gnavus'' experience symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. Patients experiencing extreme symptoms may face inflammation of the eyes, skin, and spine. | Patients experiencing Crohn's disease and an increase in ''R. gnavus'' experience symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. Patients experiencing extreme symptoms may face inflammation of the eyes, skin, and spine. Penicillin, meropenem, tetracycline, metronidazole and clindamycin are antibiotics that can work against ''R. gnavus'', as demonstrated in vivo (7). | ||

In order to survive and thrive within the human gut, ''R.gnavus'' evolved mechanisms to adapt to their environment. These are labeled "microbial colonization factors". ''Ruminococcus gnavus'' produce antimicrobial peptides called bacteriocins to inhibit the growth of other potential competitors. It has also evolved to produce a range of carbohydrate-active enzymes, allowing them to metabolize complex carbohydrates. | In order to survive and thrive within the human gut, ''R.gnavus'' evolved mechanisms to adapt to their environment. These are labeled "microbial colonization factors". ''Ruminococcus gnavus'' produce antimicrobial peptides called bacteriocins to inhibit the growth of other potential competitors. It has also evolved to produce a range of carbohydrate-active enzymes, allowing them to metabolize complex carbohydrates. | ||

''R. gnavus'' has positive and negative associations with human diseases, both intestinally and extraintestinally. These diseases range from inflammatory bowel disease to neurological diseases (3). ''R. gnavus'' blooms as symptoms of Crohn’s disease worsen. Inflammatory cytokines produced by ''R. gnavus'' may contribute to this relationship (4). Tryptamine, a product of R. gnavus secondary metabolism, assists in the release of serotonin in the brain (3). Thus, an increase of R. gnavus may positively influence serotonin production (11). Serotonin is implicated in several psychiatric and neurological conditions, rendering its metabolism an important area for research on R. gnavus (11). | |||

''R. gnavus'' has positive and negative associations with human diseases, both intestinally and extraintestinally. These diseases range from inflammatory bowel disease to neurological diseases ( | |||

[[Image:GutMicrobiome.jpg|thumb|200px|bottom| (<i>Gut Microbiome Illustration: Home of Ruminococcus gnavus and millions of microbes</i>). Image credit: Norgen Biotek Corporation.]] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

( | (1) Togo, A. H., Diop, A., Bittar, F., Maraninchi, M., Valero, R., Armstrong, N., Dubourg, G., Labas, N., Richez, M., Delerce, J., Levasseur, A., Fournier, P., Raoult, D., & Million, M. (2018). Description of mediterraneibacter massiliensis, gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus isolated from the gut microbiota of an obese patient and reclassification of ruminococcus faecis, ruminococcus lactaris, ruminococcus torques, ruminococcus gnavus and clostridium glycyrrhizinilyticum as mediterraneibacter faecis comb. nov., mediterraneibacter lactaris comb. nov., mediterraneibacter torques comb. nov., mediterraneibacter gnavus comb. nov. and mediterraneibacter glycyrrhizinilyticus comb. nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 111(11), 2107-2128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-018-1104-y | ||

( | (2) Moore, W. E, Johnson, J. L., & Holdeman, L. V. (1976). Emendation of Bacteroidaceae and butyrivibrio and descriptions of Desulfomonas gen. nov. and ten new species in the genera Desulfomonas, Butyrivibrio, Eubacterium, Clostridium, and ruminococcus. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 26(2), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-26-2-238 | ||

( | (3) Crost, E. H., Coletto, E., Bell, A., & Juge, N. (2023). Ruminococcus gnavus: friend or foe for human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 47(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuad014 | ||

( | (4) Henke, M. T., Kenny, D. J., Cassilly, C. D., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R. J., & Clardy, J. (2019). Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn's disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116(26),12672-12677. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904099116 | ||

( | (5) Zhai, L., Huang, C., Ning, Z., Zhang Y., Zhuang, M., Yang, W., Wang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, L., Xiao, H., Zhao, L., Asthana, P., Lam, Y. Y., Willis Chow, C. F., Huang, J., Yuan, S., Chan, K. M., Yuan, C., Lau, J. Y., Wong, H. L. X., & Bian, Z. (2023). Ruminococcus gnavus plays a pathogenic role in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by increasing serotonin biosynthesis. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(1), 33-44.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2022.11.006 | ||

( | (6) Crost E. H., Le Gall, G., Laverde-Gomez, J. A., Mukhopadhya, I., Flint, H. J., & Juge, N. (2018). Mechanistic Insights Into the Cross-Feeding of Ruminococcus gnavus and Ruminococcus bromii on Host and Dietary Carbohydrates. Front Microbiol, 9, 2558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02558 | ||

( | (7) Gren, C., Spiegelhauer, M. R., Rotbain, E. C., Ehmsen, B. K., Kampmann, P., & Andersen, L. P. (2019) Ruminococcus gnavus bacteraemia in a patient with multiple haematological malignancies. Access Microbiology, 1(8). https://doi.org/10.1099/acmi.0.000048 | ||

( | (8) Hall, A. B., Yassour, M., Sauk, J., Garner, A., Jiang, X., Arthur, T., Lagoudas, G. K., Vatanen, T., Fornelos, N., Wilson, R., Bertha, M., Cohen, M., Garber, J., Khalili, H., Gevers, D., Ananthakrishnan, A. N., Kugathasan, S., Lander, E. S., Blainey, P., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R. J., & Huttenhower, C. (2017). A novel Ruminococcus gnavus clade enriched in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Genome Med, 9, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-017-0490-5 | ||

( | (9) Abdugheni, R., Liu, C., Liu, F.-L., Zhou, N., Jiang, C.-Y., Liu, Y., Li, L., Li, W.-J., & Liu, S.-J. (2023, July 24). Comparative genomics reveals extensive intra-species genetic divergence of the prevalent gut commensal Ruminococcus Gnavus. microbiologyresearch.org. https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.001071 | ||

( | (10)Kegg Genome: Ruminococcus Gnavus. (2020). https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_organism?org=T06719 | ||

( | (11) Coletto, E., Latousakis, D., Pontifex, M. G., Crost, E. H., Vaux, L., Perez Santamarina, E., Goldson, A., Brion, A., Hajihosseini, M. K., Vauzour, D., Savva, G. M., & Juge, N. (2022). The role of the mucin-glycan foraging Ruminococcus gnavus in the communication between the gut and the brain. Gut microbes, 14(1), 2073784. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2073784 | ||

==Author== | ==Author== | ||

Page authored by Chris Blackwell, student of Prof. Bradley Tolar at UNC Wilmington. | Page authored by Chris Blackwell, student of Prof. Bradley Tolar at UNC Wilmington. | ||

Latest revision as of 16:49, 12 December 2023

Classification

Bacteria (Domain); Bacillota (Phylum); Clostridia (Class); Eubacteriales (Order); Lachnospiraceae (Family); Mediterraneibacter (Genus)

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=33038

Species

|

Ruminococcus gnavus Description and SignificanceDiscovered in 1974,Ruminococcus gnavus is a Gram-positive obligate anaerobe bacterium discovered first in the human gastrointestinal tract. Despite its name it is actually a part of the genus Mediterraneibacter, although retaining its Ruminococcus name for study purposes. R.gnavus is considered a part of the normal human gut microbiome in children and adults. It has been suggested that it has a role in priming the gut microbiota in association with standard weight gain velocity in infants. R. gnavus has also been linked to disease, as an overabundance of "R. gnavus" in the gut is associated with the exacerbation of symptoms of Crohn’s disease such as abdominal pain and diarrhea (4). Ruminococcus gnavus is one of few microbiota bacterium that persists at a consistent level from infancy to throughout adulthood. Studies have shown that R. gnavus is a key biomarker of health and diseases with certain immune/metabolic properties, making it an important bacterium to understand. Genome StructureRuminococcus gnavus contains circular chromosomes containing 77 RNA coding genes, 3345 protein coding genes, and 3549191 nucleotides. R.gnavus was found to have a mean genome size of 3.46±0.34 Mbp, with a mean G+C conctent of 42.73±0.33 mol%. R.gnavus' pan-core genome analysis revealed a predicted 28,072 genes, with the core genes making up 3.74% (1051) of that. Strain ATCC 29149 of R. gnavus was used for initial classification of this species into the Ruminococcus genus. The genome of strain ATCC 29149 consists of 43% G:C, which is similar to that of other species within the genus Ruminococcus (2). The genome size of strain ATCC 29149 was 3.62 Mb (1). Cell Structure, Metabolism and Life CycleRuminococcus are coccoid shaped and have not been found to produce spores (1). They can be motile or nonmotile and possess one to three flagella (2). Visually, the cells are elongated with ends that taper off. The usual dimensions of the cell are 0.9 to 1.1 picometers by 1.1 to 1.4 picometers (2).

Ecology and PathogenesisThere are a multitude of studies that show a large positive association between Crohn's disease and Ruminococcus gnavus populations. R. gnavus populations skyrocket during flare ups in Crohn's disease patients. R. gnavus produces an inflammatory glucorhamnan polysaccharide that triggers the production of inflammatory cytokines. R. gnavus may increase oxidative stress, which is often present in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (8). Patients experiencing Crohn's disease and an increase in R. gnavus experience symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. Patients experiencing extreme symptoms may face inflammation of the eyes, skin, and spine. Penicillin, meropenem, tetracycline, metronidazole and clindamycin are antibiotics that can work against R. gnavus, as demonstrated in vivo (7). In order to survive and thrive within the human gut, R.gnavus evolved mechanisms to adapt to their environment. These are labeled "microbial colonization factors". Ruminococcus gnavus produce antimicrobial peptides called bacteriocins to inhibit the growth of other potential competitors. It has also evolved to produce a range of carbohydrate-active enzymes, allowing them to metabolize complex carbohydrates. R. gnavus has positive and negative associations with human diseases, both intestinally and extraintestinally. These diseases range from inflammatory bowel disease to neurological diseases (3). R. gnavus blooms as symptoms of Crohn’s disease worsen. Inflammatory cytokines produced by R. gnavus may contribute to this relationship (4). Tryptamine, a product of R. gnavus secondary metabolism, assists in the release of serotonin in the brain (3). Thus, an increase of R. gnavus may positively influence serotonin production (11). Serotonin is implicated in several psychiatric and neurological conditions, rendering its metabolism an important area for research on R. gnavus (11). References(1) Togo, A. H., Diop, A., Bittar, F., Maraninchi, M., Valero, R., Armstrong, N., Dubourg, G., Labas, N., Richez, M., Delerce, J., Levasseur, A., Fournier, P., Raoult, D., & Million, M. (2018). Description of mediterraneibacter massiliensis, gen. nov., sp. nov., a new genus isolated from the gut microbiota of an obese patient and reclassification of ruminococcus faecis, ruminococcus lactaris, ruminococcus torques, ruminococcus gnavus and clostridium glycyrrhizinilyticum as mediterraneibacter faecis comb. nov., mediterraneibacter lactaris comb. nov., mediterraneibacter torques comb. nov., mediterraneibacter gnavus comb. nov. and mediterraneibacter glycyrrhizinilyticus comb. nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek, 111(11), 2107-2128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10482-018-1104-y (2) Moore, W. E, Johnson, J. L., & Holdeman, L. V. (1976). Emendation of Bacteroidaceae and butyrivibrio and descriptions of Desulfomonas gen. nov. and ten new species in the genera Desulfomonas, Butyrivibrio, Eubacterium, Clostridium, and ruminococcus. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 26(2), 238–252. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-26-2-238 (3) Crost, E. H., Coletto, E., Bell, A., & Juge, N. (2023). Ruminococcus gnavus: friend or foe for human health. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 47(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/femsre/fuad014 (4) Henke, M. T., Kenny, D. J., Cassilly, C. D., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R. J., & Clardy, J. (2019). Ruminococcus gnavus, a member of the human gut microbiome associated with Crohn's disease, produces an inflammatory polysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 116(26),12672-12677. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1904099116 (5) Zhai, L., Huang, C., Ning, Z., Zhang Y., Zhuang, M., Yang, W., Wang, X., Wang, J., Zhang, L., Xiao, H., Zhao, L., Asthana, P., Lam, Y. Y., Willis Chow, C. F., Huang, J., Yuan, S., Chan, K. M., Yuan, C., Lau, J. Y., Wong, H. L. X., & Bian, Z. (2023). Ruminococcus gnavus plays a pathogenic role in diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome by increasing serotonin biosynthesis. Cell Host & Microbe, 31(1), 33-44.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2022.11.006 (6) Crost E. H., Le Gall, G., Laverde-Gomez, J. A., Mukhopadhya, I., Flint, H. J., & Juge, N. (2018). Mechanistic Insights Into the Cross-Feeding of Ruminococcus gnavus and Ruminococcus bromii on Host and Dietary Carbohydrates. Front Microbiol, 9, 2558. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02558 (7) Gren, C., Spiegelhauer, M. R., Rotbain, E. C., Ehmsen, B. K., Kampmann, P., & Andersen, L. P. (2019) Ruminococcus gnavus bacteraemia in a patient with multiple haematological malignancies. Access Microbiology, 1(8). https://doi.org/10.1099/acmi.0.000048 (8) Hall, A. B., Yassour, M., Sauk, J., Garner, A., Jiang, X., Arthur, T., Lagoudas, G. K., Vatanen, T., Fornelos, N., Wilson, R., Bertha, M., Cohen, M., Garber, J., Khalili, H., Gevers, D., Ananthakrishnan, A. N., Kugathasan, S., Lander, E. S., Blainey, P., Vlamakis, H., Xavier, R. J., & Huttenhower, C. (2017). A novel Ruminococcus gnavus clade enriched in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Genome Med, 9, 103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-017-0490-5 (9) Abdugheni, R., Liu, C., Liu, F.-L., Zhou, N., Jiang, C.-Y., Liu, Y., Li, L., Li, W.-J., & Liu, S.-J. (2023, July 24). Comparative genomics reveals extensive intra-species genetic divergence of the prevalent gut commensal Ruminococcus Gnavus. microbiologyresearch.org. https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/mgen/10.1099/mgen.0.001071 (10)Kegg Genome: Ruminococcus Gnavus. (2020). https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_organism?org=T06719 (11) Coletto, E., Latousakis, D., Pontifex, M. G., Crost, E. H., Vaux, L., Perez Santamarina, E., Goldson, A., Brion, A., Hajihosseini, M. K., Vauzour, D., Savva, G. M., & Juge, N. (2022). The role of the mucin-glycan foraging Ruminococcus gnavus in the communication between the gut and the brain. Gut microbes, 14(1), 2073784. https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2022.2073784 AuthorPage authored by Chris Blackwell, student of Prof. Bradley Tolar at UNC Wilmington. |