Reptile-Exotic-Pet-Associated-Salmonellosis

By Tomas Grant

Introduction

Introduce the topic of your paper. What microorganisms are of interest? Habitat? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Salmonella spp. are rod-shaped, flagellated, and facultative anaerobic bacteria which belong to the family Enterobacteriaceae, and as apart of the phylum Proteobacteria are Gram-negative. The genus Salmonella consists of two species S. enterica and S. bongori , the majority of the diversity lies within the more than 2,600 servovars of the species S. enterica . The three main servers within this species are (1) S. typhi, the cause of systemic infections and typhoid fever, (2) S. Enteritidis, a major food cause of food poisoning associated with poultry farming, and (3) S. typhimurium, which is not fatal in humans, but may cause gastroenteritis, but also more serious cases including septicemia, meningitis, and subnormal empyema. (Rabsch et, al, “The Zoonotic agent Salmonellosis).

Salmonellosis is one of the most common foodbourne diseases and can be caused by the various serovars of the species S. enterica , and is found worldwide, causing 93.8 million cases of gastroenteritis and over 155,00 deaths annually worldwide (Noellie et el 2014). Understanding the pathology of foodbourne Salmonellosis is important however, there is an increasing concern for Reptile-Exotic-Pet-Associated-Salmonellosis (REPAS ), in which Salmonella serovars act as major zoonotic agents of infection through direct or indirect animal contact in people’s homes, veterinary clinics, farms, zoological gardens, and other professional, public and private settings. (Rabsch et, al, “The Zoonotic agent Salmonellosis) . There are a number of reports that describe the prevalence of Salmonella spp. in reptiles ranging from lizards, snakes, and turtles, and multiple serovars have been identified and shown to be associated with each of these organisms (Sylvester et al, 2014). Reptiles have been shown to be asymptomatic carriers of Salmonella and have been shown to have a natural interaction with the bacteria, with these bacteria being natural inhabitants of reptile gut microflora, shredded at various rates throughout the reptile’s lifecycle. (INSERT) Figure showing prevalence of Salmonella by Species

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki. The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Classification

Higher order taxa:

Kingdom:Bacteria

Phylum: Proteobacteria

Order: Gammaproteobacteria

Suborder: Enterobacteriales

Family: Enterobacteriaceae

Genus: Salmonella

Species:

Salmonella enterica subsp. I serovar Typhimurium (S. typhimurium LT2), S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi (S. typhi CT18), S. enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhi Ty2 (S. typhi Ty2)

NCBI: Taxonomy Genome: S. typhi CT18 S. typhi Ty2 S. typhimurium|}

Epidemiology

Transmission of Salmonella

The main pathway of transmission for Salmonella spp. is via the fecal-oral route usually beginning with the ingestion of contaminated food or water so that the bacterium can reach the intestinal epithelium, spreading throughout the gastrointestinal tract causing gastroenteritis. Humans typically acquire the organisms through direct transmission through handling of a reptile, and via indirect transmission by contact with an object contaminated by a reptile. Other sources of transmission include aquariums, terrariums, cages, as well as the water that most reptiles like turtles and amphibians live in. Clothing that has come into direct contact with reptiles has been associated as a source of transmission, and also bites and claw scratches have been shown to be effective at transmitting Salmonella spp.

Salmonella has been shown to be able to survive for long periods of time in the environment and especially in those environments where it is wet and warm, and has been isolated for prolonged periods from surfaces contaminated by reptile feces (Centers for Disease Control, Jan 2013). It is of important note to highlight the fact that the CDC found that Salmonella has been reported to “survive 89 days in tap water, 115 days in pond water, within dried reptile feces from cages 6 months after removal of the reptile, and from aquarium water 6 weeks after removal of a turtle (CDC, Jan 2013). These findings alone show the danger associated with such a long living organism and help demonstrate the prevalence of the disease Salmonellosis and the dangers associated with Salmonella as a world-wide issue.

Pathology and Immune Response

Clinical Signs of Infection

Patients infected by Salmonella typically present a multitude of symptoms including an acute onset of fever, cramping, abdominal pain, diarrhea with or without blood associated with inflammation of the large bowel, as well as nausea and vomiting, but there is a wide spectrum of severity of the illness which may be indicated by only a few or a multitude of symptoms (Fabrega and Vila, 2013). The disease usually manifests after the ingestion of >50,000 bacteria in contaminated food, water, or other sources of infection and non-typhoidal, self-limiting, Salmonella gastroenteritis requires an incubation period ranging from 6 to 72 hours depending on susceptibility and inoculum (CDC Jan 2013). Whether or not Salmonella remains within the intestine or disseminates to other major organs depends on host immune response as well as the virulence of the strain.

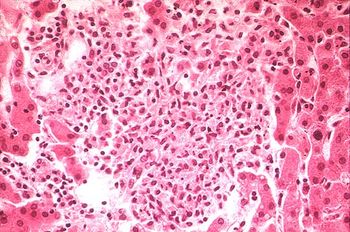

Pathogenesis of Salmonella serovar S. Typhimurium

The pathogenesis triggered by the Salmonella serovar S. Typhimurium has been studied extensively and knowledge about its multitude of virulence mechanisms for successfully invading host tissue cells has been compiled. These organisms have a large armamentarium of virulence factors all regulated by an extremely complicated regulatory network, responsible for coordinating and synchronizing all the elements involved. This regulatory mechanism is important because it guarantees the expression of each individual virulence element, but it also facilitates a cross talk between all of the determinants, ensuring the bacteria responds appropriately at all stages in a temporal hierarchal method. These elements include Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPI’s), as well as other virulence determinants, such as those encoding with the pSLT virulence plasmid, adhesions, flagella, and biofilm-related proteins which all contribute to several stages of the disease (Fabrega and Vila, 2013).

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Antibiotic Resistance and Treatment

Risks Associated With S. enterica infections

Risk Factors

Disease Prevention Measures

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

References

[1] Fàbrega, Anna, and Jordi Vila. "Salmonella Enterica Serovar Typhimurium Skills to Succeed in the Host: Virulence and Regulation." Clinical microbiology reviews 26.2 (2013): 308-41.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2015, Kenyon College.