Taenia solium’s Neurological Effect on Epilepsy in Developing Countries

Background

By [Joy Head]

Neurocysticercosis is the leading cause of seizures and epilepsy in developing countries and the most common parasitic disease of the CNS [1]. Although it millions of people have this parasitic infection, it is very much so preventable. In industrialized countries, it is usually seen in immigrants due to humans being intermediate hosts carrying it from areas of endemic disease. In the United States, neurocysticercosis is most prevalent in California, Texas, and New Mexico and a significant factor of morbidity in the Hispanic community. However, there have been cases where natives have gotten the disease due to their food being handled by a carrier of Taeniasis or T. solium[2].

Neurocysticercosis is endemic in Central and South America, China, Africa, and Asia, with the except of Japan, Israel, and Muslim countries, due to the lack of control in domestic pig-raising and improved sanitation. Pigs are usually killed clandestinely to preserve commercial value. Because only a few cuts are usually made the inspection of the carcass is overlooked, often missing signs of mild infections. Even though cysticercosis reduces the commercial value of pigs and cattle, the system pressures farmers to slaughter pigs illegally and ignore the distribution of infected meat[3].Developed countries like the United States have for the most part eradicated cysticercosis by controlling domestic pig-raising and having strict sanitation rules. Due to lack of socioeconomic growth in endemic, intervention methods for controlling and eradicating the transmission of T. solium in pigs is needed. My question is to investigate what has made this infection a neglected parasite infection in the USA but also the leading cause of onset epilepsy worldwide by looking at developing countries.

Pathophysiology

T. solium has been found to be endemic in Latin America, India, China due to poor sanitation and living conditions. This allowed for pigs to come into contact with human faeces and increased the risk of human cysticercosis in these areas. In addition, the disease was spread quickly by migration from the countryside to urban slums[4].

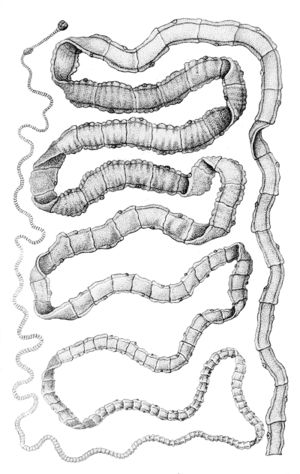

T. solium is a member of the Taeniidae family that is grouped with cyclophyllid cestodes. Because it’s found anywhere where pork is eaten, the tapeworm is found all over the world. It is more prevalent in developing countries with poor sanitary conditions of pig-raising. The adult pork tapeworm is white in color and has a flat, ribbon-like body that is 2 to 3 meters long. In some cases, it can get up to 8 m long and can be found in humans. The head, a scolex, is 1 mm in diameter and composed of suckers and a rostellum that are used for attachment on the host’s intestinal wall. The rostellum has two rows of spiny hooks similar to chitin. The strobila, the main body, consists of 800 to 900 proglottides that are each reproduce units (hermaphrodite). Tegument covers the entire body with an absorptive layer of microtriches. Figure 1 displays the 22 to 32 rotelllar hooks that can be differentiated into short (130-µm) and long (180-µm) types[5].

Pigs are the intermediate host for the Taenia solium tapeworm while humans are definitive hosts. The pork tapeworm is transmitted to pigs via human faeces or contaminated animal feed. In humans, Taenia solium is transmitted through uncooked or undercooked pork. When pigs ingest embryonated eggs or the proglottids of Taenia solium, the eggs hatch and infiltrate the intestinal wall to travel to skeletal muscle. The larvae mature over the next the next 2-3 months into encysted cysticerci. The cysticerci can survive in the tissues from months to years and repress the pig's inflammatory response.

The life cycle of Taenia solium is completed when humans accidentally ingest uncooked or undercooked pork containing cysticerci. People can develop cysticercosis much like pigs but can go years without experiencing any symptoms. There are incidences in Asia that 1-2 cm solid lumps have developed under the skin, but months or years later they become inflamed[6]. The infectious disease occurs after the embryonated eggs of the pork tapeworm T. solium are ingested due to fecal-oral contract with carriers of adult T. solium . The eggs shed in stool and contaminate food and water through poor hygiene. After ingestion and exposure to gastric acid in the stomach, the eggs lose their protective capsule layer and turn into oncospheres. Oncospheres travel across the GI tract and spread to the brain, eyes, muscle, and other structures through the vascular system. The larvae complete development at 2 months and are a translucent white with an elongated oval shape reaching 0.6 to 1.8 cm in length. 2.5 million people in the world are carrying this worm[7][8][9].

The most common location of cysticercosis is in the central nervous system, which causes the most severe type: neurocysticercosis. Once the larval cysts are in the brain, neurological symptoms can occur. Epileptic seizures are the most common neurologic syndrome in developing countries. It is estimated to cause 50% of adult-onset seizures where T. solium is endemic. The cysts suppress immune responses and can remain for years in the brain. In the brain, cysts usually form in the parenchyma. This causes seizures and sometimes headaches. Cysticerci in the brain are between 5-20 mm in diameter and can cause lesions as large as 6 cm in diameter in subarachnoid space and fissures. This is what leads to a severe headache, blindness, convulsions, and epileptic seizures, and sometimes death[10]. Cysts localized in the ventricles of the brain have the risk of blocking the outflow of cerebrospinal fluid and display symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Symptoms of ICP consist of headaches, vomiting (without nausea), ocular palsies, a lower level of consciousness, back pain, and papilledema. If papilledema becomes chronic, it can cause visual disturbances, optic atrophy, and eventually lead to blindness. Cysts in the subarachnoid space, racemose neurocysticercosis, can grow into lobulated masses that's size can inflict pressure on surrounding structures. Neurocysticercosis associated with the spinal cord results in back pain and radiculopathy[11]

Diagnosis

Rarely do patients with cysticercosis carry the tapeworm, so stool studies are not done for diagnosis. Diagnosis requires a biopsy of the infected tissue or advanced instruments. Cysticercosis is usually diagnosed by parasite eggs in the faeces; however, for the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis, the epidemiology, symptoms, serological analysis, neuroimaging, and pathology must be taken into account. Most patients have lived in endemic areas of Taenia solium for extended periods of time. For patients from non-endemic areas, a different method of diagnosis is pursued as well as an investigation of the source. These patients could have been exposed by short-term travel to endemic areas or had their food handled by carriers of T. solium. A biopsy of skin nodules might also be used in addition to these tests[12].

Signs of neurocysticercosis are often unspecific compared to other diseases. Common symptoms are seizures, headache, focal findings, and intracranial hypertension. Seizures are usually focal with the generalization of manifestation. Most are a result of the degenerating cysts or calcified granulomas. Focal findings are uncommon and a result of lesions and mechanisms. Headaches are often common but nonspecific and accompanied by seizures. Often neurocysticercosis has the complication of hydrocephalus and intracranial hypertension and can appear as headache, nausea, vomiting, loss of consciousness, and a variety of other findings such as dementia[13].

Neuroimaging is essential to the diagnosis of NCC. The most useful CNS imaging are CT and MRI. MRI is superior to displaying intraventricular or subarachnoid cysts and inflammation. Although MRI is a more advanced at imaging brain structure and anatomy, CT scans without contrast can identify calcified and uncalcified cysts and can distinguish active cysts from inactive cysts. When cysts are active they are asymptomatic. They appear as a round, hypodense area on a CT scan. Both scans show the existence of an eccentric mural nodule, which is pathognomonic of neurocysticercosis. When the cyst degenerates, it enhances the contrast of the hypodense appearance on the CT. The MRI struggles to show these degenerating cysts going through a transitional stage. After the cyst completes its life cycle and dies, it will either disappear or become an inactive calcified nodule of homogenous high density on a CT and be of low intensity on proton weighted MRI[14].

Serological analysis, has a number of tests measuring antibodies to Taenia solium. The best documented serological test is the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot assay (EITB), which has sensitivity and specificity of more than 98% than any other test for cysticercosis[15]. Patients with intracranial lesions and calcified cysts could be seronegative, so the CDC’S immunoblot assay can be used to react with structural glycoprotein antigens of the larval cysts, but not an available resource for most clinical practices and nearly impossible to get in resource limited settings, such as endemic regions[16].

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ "The causal relationship between neurocysticercosis infection and the development of epilepsy - a systematic review" Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2017 6:31

- ↑ "Neurocysticercosis" Medscape 2016

- ↑ "Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy in developing countries" Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2000

- ↑ "Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy in developing countries" Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2000

- ↑ "Taenia solium" Wikipedia 2017

- ↑ "Cysticercosis" Wikipedia 2017

- ↑ "Taeniasis/cysticercosis" World Health Organization 2017

- ↑ "Cysticercosis" Wikipedia 2017

- ↑ "Neurocysticercosis" Medscape 2016

- ↑ "Taeniasis/cysticercosis" World Health Organization 2017

- ↑ "Intracranial pressure" Wikipedia 2017

- ↑ [https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cysticercosis/health_professionals/ " Parasites - Cysticercosis" Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2014]

- ↑ "Diagnosis and Treatment of Neurocysticercosis" National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine 2011

- ↑ "Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy in developing countries" Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2000

- ↑ "Taenia solium "Neurocysticercosis" The New England Journal of Medicine 2007

- ↑ "Cysticercosis" Wikipedia 2017

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.

- ↑ [DeGiorgio, C., Medina, M., Duron, R., Zee, C. and Escueta, S. (2004). "Neurocysticercosis". Epilepsy Currents, 4(3), pp.107-111.]

- ↑ [En.wikipedia.org. (2017). Taenia solium. [online] Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taenia_solium.]

- ↑ [García, H., Gonzalez, A., Evans, C. and Gilman, R. (2003). Taenia solium cysticercosis. The Lancet, 362(9383), pp.547-556.]

- ↑ [Pal, D. (2000). Neurocysticercosis and epilepsy in developing countries. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 68(2), pp.137-143.]

- ↑ [Rajshekhar, V., Joshi, D., Doanh, N., van De, N. and Xiaonong, Z. (2003). Taenia solium taeniosis/cysticercosis in Asia: epidemiology, impact and issues. Acta Tropica, 87(1), pp.53-60.]