The Human Gut

Overview

By Mia Tran

The human gut, also known as the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, consisting of all the organs that allow for humans to consume, digest, and expel food, and is highly populated by a diverse range of microbiota that serves many crucial processes in maintaining human health, such as digestion, fighting infection, and production of key vitamins and antioxidants.[1] The microbes occupying the gut ranges to the order of 1017[2] and consists primarily of bacteria, but also includes a variety of protozoa, archaea, prokaryotes, and viruses.[3]

Detailed Environmental Description

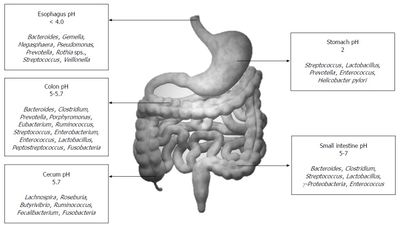

The physical environment of the GI tract consists of an interface ranging from 250-400 square meters in an adult human.[4] The distribution of microbiota within this interface depends greatly on various gradients existing in the gut, such as nutrient and chemical gradients.[4] Microbes tend to sit either in the lumen or mucosa, and very rarely penetrates the bowel wall, as most microbes that achieve this tend to be pathogenic.[1]

The biogeochemical landscape of the gut various from organ to organ. The small intestine, the first organ in the tract following the stomach, is characterized by low pH, high oxygen, and an abundance of antimicrobials.[4] These conditions allow for limiting microbe growth, just so facultative anaerobes begin to settle to the mucus lining of the intestine, making way for an environment conducive for obligate anaerobes.[4] In the colon, or large intestine, there is a much more densely populated and diverse microbiota.[4] Communities of bacteroides, streptococci, and clostridia can outnumber facultative anaerobes up to a ratio of 1000:1.[1] The pH gradient and corresponding microbial communities are summarized in the figure to the left.[5]

Leading up to the formal study of the gut microbiota, breakthroughs in culturing anaerobes in 1944[6] and using a faecal transplant to treat a Clostridioides difficile infection in 1958[7] were some first breakthroughs in the field. The study of microflora in the human gut formally began in 1960s, where much of the initial research began with experiments using germ-free animals,[8] and studying the composition and count of microbes. At the time, most of the work being done focused on strains that could be cultured. Since then, research exploded during the 2000s and 2010s due to the development of sequencing technologies that allowed scientists to learn about communities that could not be cultured in the lab.

Overview of Microbial Ecology as it is known

(To be added)

Acquisition of the Gut Microbiome at Birth and Infancy

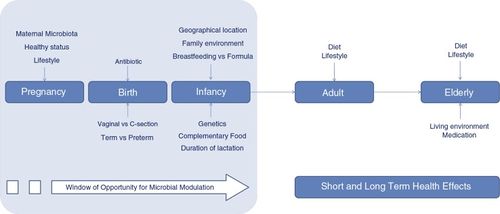

Ones gut microbiome is acquired at birth, not before. Babies are sterile within the womb, but at the moment of birth are exposed to bacteria from placenta tissue, umbilical blood, amniotic fluid, skin, and other membranes. Natural and cesarean births can have different impacts on the acquired microbiome of the babies.

After birth, the composition of microbiota is quickly changing and developing. The infant's diet of breastmilk or formula, as well as various environmental factors can shift the communities in its gut for its first few years of life. It is common for there to be initially low diversity, as the Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria phyla dominate. As the child matures, usually after the first year, the gut experiences higher diversity dominated by the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes.

Factors Changing the Composition of Gut Microbiota During Adulthood

(To be added)

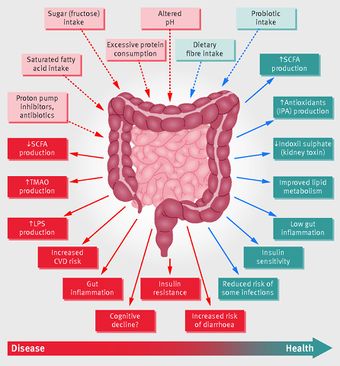

Dysbiosis: Health Impacts of Disrupted Microflora

(To be added)

Key Microbial Players

As mentioned before, the majority of the microbes in the human gut are bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes, then the Bacteroidetes phyla. A majority of the bacteria cannot be cultured, which is why the development of technologies such as 16s RNA sequencing has allowed the scientific community to unlock more about the composition of the gut microflora.

Within the gut, these bacteria are able to perform a variety of functions crucial to the human body. Enterohepatic circulation is mediated by these communities, which moves substances from the liver to bile, to the small intestine for absorption, then back to the liver; this overall serves the purpose of aiding digestion and absorption of substances like drugs and important acids.

These bacteria are also responsible for the breaking down of fiber, a very complex molecule that can be difficult even past the stomach. Some key molecules, such as vitamins, can be secreted by certain strains of bacteria.

Additionally, low levels of more harmful bacteria, such as Clostridium difficile can serve as a defense mechanism against foreign pathogens entering the GI tract, preventing infections.

Conclusion

(To be added)

References

(To be added)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Gorbach SL. "Microbiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract." In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 95.

- ↑ Sender R., Fuchs S., and Milo R. "Revised Estimates for the Number of Human and Bacteria Cells in the Body." PLOS Biology 14(8): e1002533. 2016

- ↑ Kho Zhi Y., Lal Sunil K. "The Human Gut Microbiome – A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease." Frontiers in Microbiology, Vol.9. 2018

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Thursby, E., and Juge, N. "Introduction to the human gut microbiota" Biochemical Journal, Vol.474(11),1823-1836. 2017

- ↑ Jandhyala, S.M., Talukdar, R., Subramanyam, C., Vuyyuru, H., Sasikala, M., and Reddy, D.N. "Role of the normal gut microbiota" World Journal of Gastroenterology : WJG, Vol.21(29),8787-8803. 2015

- ↑ Clark, H. "Culturing anaerobes." Nature Research. 2019

- ↑ Stone, L. "Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridioides difficile infection." Nature Research. 2019

- ↑ Brunello, L. "Gut microbiota transfer experiments in germ-free animals." Nature Research. 2019

Authored for Earth 373 Microbial Ecology, taught by Magdalena Osburn, 2020, NU Earth Page.