The Human Gut Microbiome and Depression and Anxiety: Difference between revisions

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

===Stress and the HPA Axis=== | ===Stress and the HPA Axis=== | ||

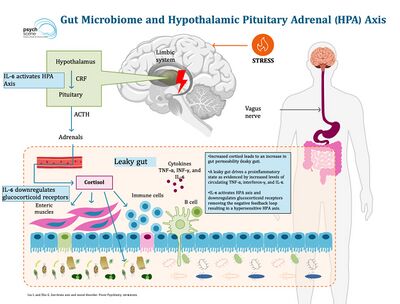

<br> The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is a bidirectionally oriented neurological pathway and mechanism that regulates and communicates stress signals and responses throughout the human body by chemical feedback.[[#References|[12]]] Stress, the state of disturbed homeostasis that occurs in case of a real or perceived threat which is a major symptom of anxiety, activates the release and secretion of epinephrine from adrenal glands, and the surge of epinephrine triggers the HPA axis beginning the cascade of events of corticotropin-release factor (CRF) secretion and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) synthesis and release.[[#References|[12]]][[#References|[13]]] The synthesized biochemical molecules further stimulate the synthesis and release of hormones that play a key role in maintaining homeostasis in response to stress known as glucocorticoid hormone cortisol.[[#References|[12]]] The multilevel stress response mechanism can be highly affected and representative of the gut microbiome condition and state of health.[[#References|[13]]] Gut microbiota can cause hyperactivity of the HPA axis through several mediators, such as antigens, cytokines, and prostaglandins, crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and by affecting the ileal corticosterone production.[[#References|[13]]] The gastrointestinal barrier regulates gut permeability and autoimmunity and is found to induce intestinal membrane permeability (leaky gut syndrome) and increase autoimmunity upon high exposure to stress and HPA axis activity. Intestinal microbiota determines the integrity of the BBB and can cause impairment leading to abnormal chemical membrane crossing and induced HPA axis exertion. Although many types of stress exist, a common stress-induced factor leading to alterations of the gut microbiota and dysfunction of the gut barrier has been found to be caused by early-life stress events primarily examined in the context of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, as well as childhood adversity such as dysfunctional family, school, and neighborhood environments and economic strain.[[#References|[12]]][[#References|[13]]] The further stimulation of the HPA axis leading to hyperactive exertion of the neural pathway and increased anxiety is both a cause and result of a dysfunctional gut microbiome ecosystem. | <br> The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is a bidirectionally oriented neurological pathway and mechanism that regulates and communicates stress signals and responses throughout the human body by chemical feedback.[[#References|[12]]] Stress, the state of disturbed homeostasis that occurs in case of a real or perceived threat which is a major symptom of anxiety, activates the release and secretion of epinephrine from adrenal glands, and the surge of epinephrine triggers the HPA axis beginning the cascade of events of corticotropin-release factor (CRF) secretion and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) synthesis and release.[[#References|[12]]][[#References|[13]]] The synthesized biochemical molecules further stimulate the synthesis and release of hormones that play a key role in maintaining homeostasis in response to stress known as glucocorticoid hormone cortisol.[[#References|[12]]] The multilevel stress response mechanism can be highly affected and representative of the gut microbiome condition and state of health.[[#References|[13]]] Gut microbiota can cause hyperactivity of the HPA axis through several mediators, such as antigens, cytokines, and prostaglandins, crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and by affecting the ileal corticosterone production.[[#References|[13]]] The gastrointestinal barrier regulates gut permeability and autoimmunity and is found to induce intestinal membrane permeability (leaky gut syndrome) and increase autoimmunity upon high exposure to stress and HPA axis activity. Intestinal microbiota determines the integrity of the BBB and can cause impairment leading to abnormal chemical membrane crossing and induced HPA axis exertion. Although many types of stress exist, a common stress-induced factor leading to alterations of the gut microbiota and dysfunction of the gut barrier has been found to be caused by early-life stress events primarily examined in the context of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, as well as childhood adversity such as dysfunctional family, school, and neighborhood environments and economic strain.[[#References|[12]]][[#References|[13]]] The further stimulation of the HPA axis leading to hyperactive exertion of the neural pathway and increased anxiety is both a cause and result of a dysfunctional gut microbiome ecosystem. | ||

===Diet Quality Effects=== | ===Diet Quality Effects=== | ||

Latest revision as of 19:40, 14 April 2024

Introduction

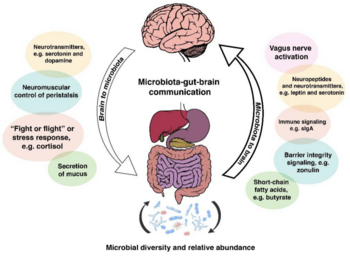

By Hailey Moss

Humans exist in a microbial world. Microbes have inhabited the Earth for hundreds of millions of years, and humans have always coexisted with bacteria internally in the human body and externally in the environment.[1] Human physiology and the inhabiting gut bacteria once studied and thought to be separate mechanisms have recently been researched to a greater degree due to the discovery of the strong converse relationship between the microscopic residents' and human’s health and physiology. The trillions of microorganisms living mostly symbiotically within and on the human body are most commonly referred to as the microbiota, the ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, archaea, and fungi within the host's central nervous system (CNS).[2] These symbionts are very important regulators of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, which is the interaction of the brain and gut through the body’s biochemical signaling pathways: the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, the vagus nerve and the enteric nervous system, including microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, branched-chain amino acids, and peptidoglycans.[1] The gut-brain axis influences cognitive functioning and mood via these neural, hormonal, metabolic, and immune-mediated mechanisms.[2]

The gut microbiota has been found to have a powerful correlation with many psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety.[2] Depression and anxiety are debilitating and ubiquitous psychiatric conditions estimated to affect 10% of the world's population according to The World Health Organization.[2] The two comorbid conditions are seen to dually affect approximately 60% of those experiencing either anxiety or depression. [4] It is reportedly twice as likely for girls to develop clinical depression and anxiety starting around age 13 to 15 as opposed to boys, although these psychiatric conditions become more co-current in males and females approaching adulthood. [3] Similar to many other psychological disorders, depression, and anxiety are conditions that exhibit an extensive range of symptoms and severity, and the conditions manifest differently in each person affected by the disorders.

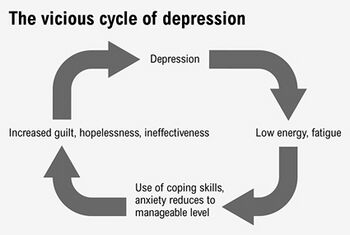

Depression and Anxiety

Depression is identified by long-term sadness and a constantly negative mood affecting everyday function, activities, and normal behaviors. Depression is estimated to affect 1 in every 6 adults at some point in their life in The United States.[5] Some common symptoms are feeling sad or anxious often; feeling irritable‚ easily frustrated‚ or restless; abnormal sleep schedule and eating patterns; experiencing aches, pains, headaches, or stomach problems that do not improve with treatment; having trouble concentrating and making decisions; feeling guilty, worthless, or helpless; experiencing thoughts of self-harm, and more.[5] The broad range of symptoms and severity of the condition can lead to a wide variety of functionality from person to person. Some cases of the disorder are moderate and lifestyle changes are minimal. Other cases can be debilitating. The severity of depressive disorders varies and the more critical cases include major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder, each of which causes significant impairments of functionality in everyday life.[6]

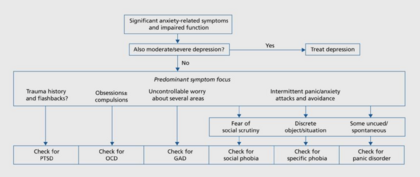

A low level of anxiety on the other hand is a common part of life, however, clinical anxiety disorders are caused by high levels of anxiousness and fear. People with anxiety disorders experience frequent intense, excessive worry and fear about everyday situations. The anxiety can be accompanied by episodes of sudden feelings of intense worry and fear or terror that heightens to a peak within minutes, known as a panic attack.[7] Common side effects are nervousness, a sense of impending danger or doom, increased heart rate and breathing, trembling, gastrointestinal issues, trouble sleeping, and more. Some of the most frequent anxiety disorders are agoraphobia, panic disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety, and many specific phobias pertaining to a specific object or situation.[7] Anxiety can be caused by a wide array of factors stressor related and mood-related, and in many cases coincides with many other physiological disorders some being depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[8]

Treatments

Throughout history, there have been many evolutions of treatment for both depression and anxiety. Firstly, exploring family history and identifying any possible genetically heritable disorders, such as major depression and bipolar disorder, has been a useful tool in diagnosing patients.[9] Along with physical inspections of the health state of the human body, questionnaires are also a prevalent source for physiological symptoms opposed to physical symptoms.[9] A drug-based development of treatment became a popular tactic to treat anxiety and depression targeting serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the brain. This treatment direction is supported by the major theory of depression known as the monoamine-deficiency hypothesis, which can also be related to a comorbid psychiatric condition like anxiety.[9] Three common types of drugs use biologically targeted agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), dual-action agents which inhibit the body’s reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) that increase concentrations of neurotransmitters by inhibiting their degradation. Other drug therapies include mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics, and atypical antipsychotics.[9] There have also been many successful treatments by nonpharmacologic therapies such as psychotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy, and monitoring and educating the patient. These treatments involve reshaping human behaviors and actions through cognitive shaping and building therapy.[9] Although these treatment techniques have proven to be beneficial for most patients, some psychological disorders are related to other conditions of the body that can expand alternative treatment options upon biological exploration.

Anxiety and Depression’s Correlation with the Gut-Brain Axis

The human gut microbiome consists of thousands of species of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites.[9] The human gut is made up of 12 different phyla, and 90% of the gut consists of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. [14] Most of which have a necessary role in regulating the homeostasis of the human body, however, when the microbial environment is interrupted and made dysfunctional due to stress, diet, antibiotics, or infection, dysbiosis occurs.[9] Dysbiosis is the lack of normal interaction between the coexisting microbes and their host resulting in host susceptibility to mental, emotional, and physical diseases.[9] Abnormal levels of the common commensal bacteria found in patients with a major depressive disorder are increased levels of phyla Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, and Actinobacteria, and reduced amounts of Firmicutes.[19] The dysregulation of the gut microbiome has been closely associated with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression. Stress, specifically early life stress (ELS), and dietary patterns are two leading causes of a misregulated gut microbiome found to worsen, if not cause, symptoms of anxiety and depression.[10][11]

Stress and the HPA Axis

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is a bidirectionally oriented neurological pathway and mechanism that regulates and communicates stress signals and responses throughout the human body by chemical feedback.[12] Stress, the state of disturbed homeostasis that occurs in case of a real or perceived threat which is a major symptom of anxiety, activates the release and secretion of epinephrine from adrenal glands, and the surge of epinephrine triggers the HPA axis beginning the cascade of events of corticotropin-release factor (CRF) secretion and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) synthesis and release.[12][13] The synthesized biochemical molecules further stimulate the synthesis and release of hormones that play a key role in maintaining homeostasis in response to stress known as glucocorticoid hormone cortisol.[12] The multilevel stress response mechanism can be highly affected and representative of the gut microbiome condition and state of health.[13] Gut microbiota can cause hyperactivity of the HPA axis through several mediators, such as antigens, cytokines, and prostaglandins, crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and by affecting the ileal corticosterone production.[13] The gastrointestinal barrier regulates gut permeability and autoimmunity and is found to induce intestinal membrane permeability (leaky gut syndrome) and increase autoimmunity upon high exposure to stress and HPA axis activity. Intestinal microbiota determines the integrity of the BBB and can cause impairment leading to abnormal chemical membrane crossing and induced HPA axis exertion. Although many types of stress exist, a common stress-induced factor leading to alterations of the gut microbiota and dysfunction of the gut barrier has been found to be caused by early-life stress events primarily examined in the context of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, as well as childhood adversity such as dysfunctional family, school, and neighborhood environments and economic strain.[12][13] The further stimulation of the HPA axis leading to hyperactive exertion of the neural pathway and increased anxiety is both a cause and result of a dysfunctional gut microbiome ecosystem.

Diet Quality Effects

Nutrition plays a very vital role in the integrity and strength of the gut microbiome which closely correlates to conditions such as behavioral health disorders. It has been found that nutrients, including tryptophan, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, folic acid (folate), phenylalanine, tyrosine, histidine, choline, and glutamic acid are imperative for the production of many neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, which are involved in the regulation of mood, appetite, and cognition.[11] It has also been found that dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotransmission, when steadily regulated by a healthy level of marine-derived omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, can decrease symptoms of many behavioral disorders, primarily anxiety and depression.[11] Dieting and mental health have a bidirectional relationship. On one hand, a poor diet could be the cause and/or result of a mental health disorder producing a vicious negative feedback loop that potentially expedites the worsening condition of both one’s nutritional and mental health. On the other hand, mental well-being couples with healthy lifestyle habits such as a healthy diet and adequate physical activity, which positively reinforces beneficial nutritional well-being.[11] Depression is a complex disorder and has no single cause, however, over the past decade, there has been a measurable parallel between increasing depressive disorders and decreasing quality of lifestyle practices including poorer diet value. Depressive symptoms are increased by deficiencies of macronutrients, such as carbohydrates, protein, and fats, and micronutrients, such as vitamin B, vitamin D, and magnesium.[11] Other research has been conducted about nutrient deficiencies causing anxiety symptoms and disorders. Scientific evidence suggests marine-derived omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, fatty fish, and micronutrients (magnesium, zinc, some vitamins), the amino acids lysine and arginine, and a multivitamin and mineral supplements are important factors in preventing and treating anxiety.[11] An example of gut microbiota and micronutrients correspondence is Bifidobacterium which synthesizes riboflavin, niacin, and folate. Low folate levels are associated with depression and anxiety disorders and folate augmentation is efficacious in depression.[13]

Depression and Anxiety Comorbidities with IBD

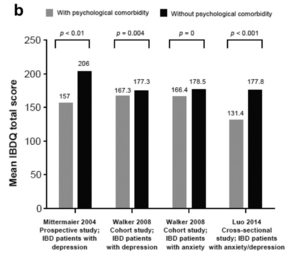

When considering anxiety or depression usually the other disorder is also tested and examined due to the high comorbidity between the two psychiatric disorders. In a study from 2011, researchers found that between 67-75% of people with a depressive disorder had a current or lifetime comorbid anxiety disorder as well. Reversely, they found that 63-81% of people with an anxiety disorder also experienced a comorbid depressive disorder.[14] More commonly in comorbid cases, anxiety disorders precede depressive disorders by approximately 40%.[14] Although most commonly related to each other, anxiety and depressive disorders have also been found to have high comorbidities with inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD), such as Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).[15] Studies found that the presence of IBD or psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression, makes contracting the other type of disorder more likely due to the comorbidity between the gut, digestive system, and the brain.[15] In a comorbid case of IBD and anxiety and depression, the remission of IBD symptoms correlated to a decrease in psychiatric symptoms. When either type of disorder went without diagnosis or treatment, the coupling, comorbid disorder, originally not the onset issue, was found to appear mirroring the unhealthy internal body state through the gut-brain connection.[15] Depressive and anxiety symptoms, in an IBD and psychiatric comorbid case, are more highly active in the period of high bowel inflammation and recede parallel to the remission of the IBD condition. A common treatment of IBD is corticosteroids which have a close association with psychiatric side effects potentially causing the appearance of a comorbid psychiatric disorder.[15] Aiming to settle active symptoms and maintain remission by reducing inflammation and promoting mucosal healing of IBD through treatment, is a large focal point of research due to the harmful psychiatric effects it can cause.[15] Other treatment paths, including antibiotics discussed later, have been used to moderate symptoms of both types of disorders along with suppressing any arising comorbid disorders as well. As discussed later, some treatments, such as antibiotics, which affect the gut composition by targeting digestive inflammation cause dysbiosis of the body’s homeostatic state further causing damage to the body’s overall condition.

Psychiatric Disorder Treatment: Microbial Therapy

Antibiotics vs Probiotics

Antibiotics decrease the diversity of gut microbiota leading to susceptibility to pathogen colonization. Although different antibiotics induce different responses in the body, most induce a stress response in the commensal gut bacteria.[13] Commensal bacteria interact with the immune system to induce protective responses to avoid pathogen infection. Many gastrointestinal side effects can arise from antibiotic treatments commonly including Clostridioides difficile infections causing diarrhea, bloating, and fever.[16] Long-term use of antibiotic remedies fosters bacterial resistance and increases resistance genes in the gut bacteria gene pool. This can lead to a deficiency in infection treatment effectiveness causing potentially untreatable lethal infections. Gut microbiota dysbiosis, along with affecting the local gut composition, globally affects the brain through the gut-brain axis making antibiotics a potentially dangerous causative of psychiatric disorders.[17] Aside from antibiotics, probiotics have more recently become an alternative and effective treatment for gastrointestinal and psychiatric disorders. Probiotics are either food that naturally contains microbiota or supplement pills that contain live active bacteria. Probiotics have proven to reduce the intensity of symptoms from pathogen infections, such as diarrhea, as well as nurture commensal gut bacteria growth and health after antibiotic damage.[9] Along with fighting dysbiosis, one study found probiotics have also been found to stabilize and strengthen the intestinal membrane barrier reducing permeability, as discussed above as leaky gut syndrome, and block bacterial translocation that occurs in cases such as IBD and depression which stimulate the HPA axis. Another study tested the effect of taking probiotics regularly over a 28-day period and found significant improvement in patient anxiety, neurophysiological anxiety, negative affect, worry, and mood regulation.[18] Gut health and psychiatric disorder treatments have more recently been treated synonymously and even more recently been treated by probiotics, so more research is still needed to comprehend the full effect and capacity of probiotic therapy.

Probiotic Treatment: Lactobacillus Trial Success

Lactobacillus is a naturally occurring bacteria inhabiting the human gut and decreases in abundance when the host experiences high levels of stress.[20][21]. It has been studied and a healthy presence of it in the gut has been found to alleviate anxiety and depression symptoms.[20] In a particular study conducted in 2021, 13 strains of Lactobacillus were examined and significant symptom relief was observed: reversing anxiety and depression symptoms caused by chronic corticosterone exposure, increasing declined serotonin levels due to chronic stress, reducing the expression and concentration of corticosterone, restoring normal behavior patterns, and improving stress-induced behavioral and cognitive impairments.[20] Patients with depressive and anxiety disorders have measurably increased activity of xanthine oxidase in the thalamus and putamen. The nervous system is negatively affected by irregular xanthine oxidase activity so its abnormal induced activity is speculated to have a correlation with depression.[20] The experiment observed xanthine oxidase activity in the presence of Lactobacillus which was projected to target neurological misregulation and alleviate psychological symptoms. Using mice as test subjects, the research results were successful and Lactobacillus treatment was successful in decreasing abnormal xanthine oxidase activity and alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms.[20] The probiotic approach to treating psychiatric disorders is relatively new and still requires further investigation. Lactobacillus is one of many probiotic success stories and demonstrates high potential for many other possible probiotic therapies.

Probiotic Limitations and Need for Future Research

It is important to understand the limitations of probiotics as a therapy method to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety. A systematic review conducted a review of many different experiments researching probiotic capabilities on the human brain in order to summarize the overall conclusions of the therapy method. The collection of data concluded that there are many varying results on the effectiveness of probiotics potentially due to differences in sample characteristics, probiotic intervention combinations, durations of trials, and outcome scales.[21] Theoretical and contextual consideration of probiotic treatment limitations are important and require both biological and social perspectives. Future research is required to collect definitive conclusions on the biological impacts all subjected humans will experience for safety purposes and increased health assurance. It is also important to consider the social repercussions of this type of treatment in order to assure continued funds for research and legal dispersal of the remedies.[21] Another area of considerable debate is the extent of effectiveness of probiotic therapy on severe psychological disorder symptoms. Further research is required to determine the effectiveness of varying severity of symptoms along with varying types of psychiatric disorders.[21] Although further exploration of probiotics is required, it is a very promising, healthy potential alternative to antibiotic treatment of psychological disorders and gut health regulation.

Conclusion

Depression and anxiety are the leading mental illnesses globally. In recent years, the firm correlation between the human gut microbiome and the brain, through the gut-brain axis, has become an essential focal point of research in hopes to remedy psychological illnesses through gut bacteria composition modification. Although future research is necessary to understand the full extent of connectivity, the gut-brain axis has been discovered to be a vital bidirectional neurological pathway with the power to significantly influence body homeostasis. There are many causative factors of depression and anxiety, a major component being dysbiosis of the human gut flora. The symptoms of the comorbid disorders resemble substantial parallels to the health and homeotic state of the gut ecosystem. There are promising therapy techniques alternative to antibiotics, which harm gut microbiota and decrease illness remediation, such as probiotic treatments coined as ‘psychobiotics’.[21] Comprehension of the connectivity between the gut microbiota and the brain is critical in the race to heal mental illness.

References

[1] Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Cowan, C. S. M., Sandhu, K. V., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Boehme, M., Codagnone, M. G., Cussotto, S., Fulling, C., Golubeva, A. V., Guzzetta, K. E., Jaggar, M., Long-Smith, C. M., Lyte, J. M., Martin, J. A., Molinero-Perez, A., Moloney, G., Morelli, E., Morillas, E., … Dinan, T. G. (2019). The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiological Reviews, 99(4), 1877–2013. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

[2] Simpson, C. A., Diaz-Arteche, C., Eliby, D., Schwartz, O. S., Simmons, J. G., & Cowan, C. S. M. (2021). The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression – A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943

[3] Chaplin, T. M., Gillham, J. E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(2), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608320125

[4] The comorbidity of anxiety and depression | nami: National alliance on mental illness. (n.d.). Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.nami.org/blogs/nami-blog/january-2018/the-comorbidity-of-anxiety-and-depression

[5] CDCTobaccoFree. (2022, September 14). Depression and anxiety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/diseases/Depression is more than just feeling down or having a bad day. When a sad mood lasts for a long time and interferes with normal, everyday functioning, you may be depressed.

[6] Penny M Kris-Etherton, Kristina S Petersen, Joseph R Hibbeln, Daniel Hurley, Valerie Kolick, Sevetra Peoples, Nancy Rodriguez, Gail Woodward-Lopez, Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: depression and anxiety, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 79, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 247–260, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa025

[7] Anxiety disorders—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

[8] Goodwin, G. M. (2015). The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(3), 249–260. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4610610/

[9] McCarter, T. (2008). Depression overview. American Health & Drug Benefits, 1(3), 44–51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4115320/

[10] Juruena, M. F., Eror, F., Cleare, A. J., & Young, A. H. (2020). The role of early life stress in hpa axis and anxiety. In Y.-K. Kim (Ed.), Anxiety Disorders: Rethinking and Understanding Recent Discoveries (pp. 141–153). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9705-0_9

[11] Penny M Kris-Etherton, Kristina S Petersen, Joseph R Hibbeln, Daniel Hurley, Valerie Kolick, Sevetra Peoples, Nancy Rodriguez, Gail Woodward-Lopez, Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: depression and anxiety, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 79, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 247–260, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa025

[12] Misiak, B., Łoniewski, I., Marlicz, W., Frydecka, D., Szulc, A., Rudzki, L., & Samochowiec, J. (2020). The HPA axis dysregulation in severe mental illness: Can we shift the blame to gut microbiota? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 102, 109951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109951

[13] Gut microbiome & depression-pathophysiology|role of pre and probiotics. (2023, March 10). Psych Scene Hub. https://psychscenehub.com/psychinsights/gut-microbiome-and-depression/

[14] Lamers, F., Oppen, P. van, Comijs, H. C., Smit, J. H., Spinhoven, P., Balkom, A. J. L. M. van, Nolen, W. A., Zitman, F. G., Beekman, A. T. F., & Penninx, B. W. J. H. (2011). Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The netherlands study of depression and anxiety(Nesda). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(3), 3397. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10m06176blu

[15] Lesley A. Graff, PhD, John R. Walker, PhD, Charles N. Bernstein, MD, Depression and Anxiety in Inflammatory Bowel Disease:A Review of Comorbidity and Management, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Volume 15, Issue 7, 1 July 2009, Pages 1105–1118, https://doi.org/10.1002/ibd.20873

[16] Maier, L., Goemans, C. V., Wirbel, J., Kuhn, M., Eberl, C., Pruteanu, M., Müller, P., Garcia-Santamarina, S., Cacace, E., Zhang, B., Gekeler, C., Banerjee, T., Anderson, E. E., Milanese, A., Löber, U., Forslund, S. K., Patil, K. R., Zimmermann, M., Stecher, B., … Typas, A. (2021). Unravelling the collateral damage of antibiotics on gut bacteria. Nature, 599(7883), 120–124. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03986-2

[17] Francino, M. P. (2016). Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: Dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Frontiers in Microbiology, 6. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01543

[18] Lee, Y., & Kim, Y.-K. (2021). Understanding the connection between the gut–brain axis and stress/anxiety disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(5), 22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01235-x

[19] Chao, L., Liu, C., Sutthawongwadee, S., Li, Y., Lv, W., Chen, W., Yu, L., Zhou, J., Guo, A., Li, Z., & Guo, S. (2020). Effects of probiotics on depressive or anxiety variables in healthy participants under stress conditions or with a depressive or anxiety diagnosis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Neurology, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2020.00421

[20] Xu, M., Tian, P., Zhu, H., Zou, R., Zhao, J., Zhang, H., Wang, G., & Chen, W. (2022). Lactobacillus paracasei ccfm1229 and lactobacillus rhamnosus ccfm1228 alleviated depression- and anxiety-related symptoms of chronic stress-induced depression in mice by regulating xanthine oxidase activity in the brain. Nutrients, 14(6), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14061294

[21] Nadeem, I., Rahman, M. Z., Ad‐Dab’bagh, Y., & Akhtar, M. (2019). Effect of probiotic interventions on depressive symptoms: A narrative review evaluating systematic reviews. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 73(4), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12804

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2023, Kenyon College