The Human Gut Microbiome and Depression and Anxiety

Introduction

By Hailey Moss

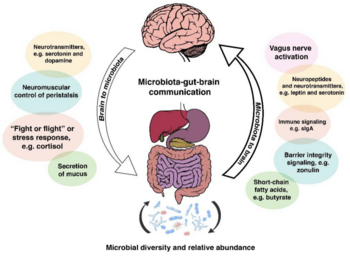

Humans exist in a microbial world. Microbes have inhabited the Earth for hundreds of millions of years, and humans have always coexisted with bacteria internally in the human body and externally in the environment.[1] Human physiology and the inhabiting gut bacteria once studied and thought to be separate mechanisms has recently been researched to a greater degree due to the discovery of the strong converse relationship between the microscopic residents' and human’s health and physiology. The trillions of microorganisms living mostly symbiotically within and on the human body are most commonly referred to as the microbiota, the ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, archaea and fungi within the host's central nervous system (CNS).[2] These symbionts are very important regulators of the microbiota-gut-brain axis, which is the interaction of the brain and gut through the body’s biochemical signaling pathways: the immune system, tryptophan metabolism, the vagus nerve and the enteric nervous system, including microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, branched chain amino acids, and peptidoglycans.[1] The gut-brain axis influences cognitive functioning and mood via these neural, hormonal, metabolic, and immune-mediated mechanisms.[2]

The gut microbiota has been found to have a powerful correlation with many psychological disorders, including depression and anxiety.[2] Depression and anxiety are debilitating and ubiquitous psychiatric conditions estimated to affect 10% of the world's population according to The World Health Organization.[2] The two comorbid conditions are seen to dually affect approximately 60% of those experiencing either anxiety or depression. [4] It is reportedly twice as likely for girls to develop clinical depression and anxiety starting around age 13 to 15 opposed to boys, although these psychiatric conditions become more co-current in males and females approaching adulthood. [3] Similar to many other psychological disorders, depression and anxiety are conditions that exhibit an extensive range of symptoms and severity, and the conditions manifest differently in each person affected by the disorders.

Depression and Anxiety

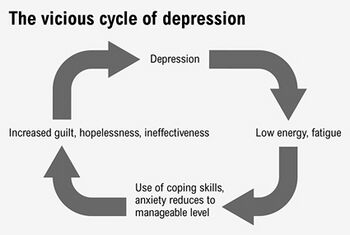

Depression is identified by long-term sadness and a constant negative mood affecting everyday function, activities, and normal behaviors. Depression is estimated to affect 1 of every 6 adults at some point in their life in The United States.[5] Some common symptoms are feeling sad or anxious often; feeling irritable‚ easily frustrated‚ or restless; abnormal sleep schedule and eating patterns; experiencing aches, pains, headaches, or stomach problems that do not improve with treatment; having trouble concentrating and making decisions; feeling guilty, worthless, or helpless; experiencing thoughts of self harm, and more.[5] The broad range of symptoms and severity of the condition can lead to a wide variety of functionality from person to person. Some cases of the disorder are moderate and lifestyle changes are minimal. Other cases can be debilitating. Severity of depressive disorders vary and the more critical cases include major depressive disorder, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder, each of which causes significant impairments of functionality in everyday life.[6]

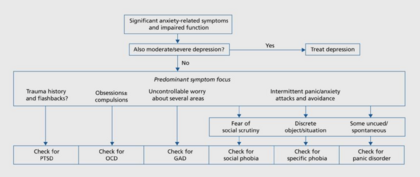

A low level of anxiety on the other hand is a common part of life, however, clinical anxiety disorders are caused from high levels of anxiousness and fear. People with anxiety disorders experience frequent intense, excessive worry and fear about everyday situations. The anxiety can be accompanied by episodes of sudden feelings of intense worry and fear or terror that heightens to a peak within minutes, known as a panic attack.[7] Common side effects are nervousness, a sense of impending danger or doom, increased heart rate and breathing, trembling, gastrointestinal issues, trouble sleeping, and more. Some of the most frequent anxiety disorders are agoraphobia, panic disorder, separation anxiety, social anxiety, and many specific phobias pertaining to a specific object or situation.[7] Anxiety can be caused from a wide array of factors stressor related and mood related, and in many cases coincides with many other physiological disorders some being depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[8]

Treatments

Throughout history there have been many evolutions of treatment for both depression and anxiety. Firstly, exploring family history and identifying any possible genetically heritable disorders, such as major depression and bipolar disorder, has been a useful tool in diagnosing patients.[9] Along with physical inspections of the health state of the human body, questionnaires are also a prevalent source for physiological symptoms opposed to physical symptoms.[9] A drug based development of treatment became a popular tactic to treat anxiety and depression targeting serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the brain. This treatment direction is supported by the major theory of depression known as the monoamine-deficiency hypothesis, which can also be related to a comorbid psychiatric condition like anxiety.[9] Three common types of drugs use biologically targeted agents such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), dual-action agents which inhibit the body’s reuptake of serotonin and norepinephrine, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) that increase concentrations of neurotransmitters by inhibiting their degradation. Other drug therapies consist of mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, antipsychotics and atypical antipsychotics.[9] There have also been many successful treatments by nonpharmacologic therapies such as psychotherapy, electroconvulsive therapy, and monitoring and educating the patient. These treatments involve reshaping human behaviors and actions through cognitive shaping and building therapy.[9] Although these treatment techniques have proven to be beneficial for most patients, some psychological disorders are related to other conditions of the body that can expand alternative treatment options upon biological exploration.

Anxiety and Depression’s Correlation with the Gut-Brain Axis

The human gut microbiome consists of thousands of species of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites.[9] The human gut is made up of 12 different phyla, and 90% of the gut consists of Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. [14] Most of which have a necessary role in regulating the homeostasis of the human body, however, when the microbial environment is interrupted and made dysfunctional due to stress, diet, antibiotics, or infection, dysbiosis occurs.[9] Dysbiosis is the lack of normal interaction between the coexisting microbes and its host resulting in host susceptibility to mental, emotional, and physical diseases.[9] The dysregulation of the gut microbiome has been closely associated with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression. Stress, specifically early life stress (ELS), and dietary patterns are two leading causes of a misregulated gut microbiome found to worsen, if not cause, symptoms of anxiety and depression.[10][11]

Stress and the HPA Axis

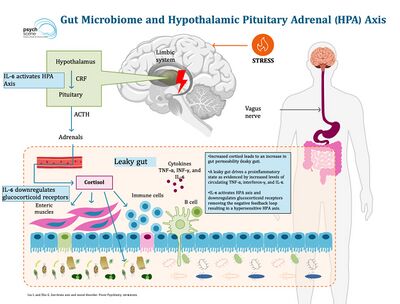

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) is a neurological pathway and mechanism that regulates and communicates stress signals and responses throughout the human body by chemical feedback.[12] Stress,the state of disturbed homeostasis that occurs in case of a real or perceived threat, activates the release and secretion of epinephrine from adrenal glands, and the surge of epinephrine triggers the HPA axis beginning the cascade of events of corticotropin-release factor (CRF) secretion and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) synthesis and release.[12][13] The synthesized biochemical molecules further stimulate the synthesis and release of hormone that plays a key role in maintaining homeostasis in response to stress known as glucocorticoid hormone cortisol.[#References|[12]]] The multilevel stress response mechanism can be highly affected and representative of the gut microbiome condition and state of health.[#References|[13]]] Gut microbiota can cause hyperactivity of the HPA axis through several mediators, such as antigens, cytokines and prostaglandins, crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and by affecting the ileal corticosterone production.[#References|[13]]] The gastrointestinal barrier regulates gut permeability and autoimmunity, and is found to induce intestinal membrane permeability (leaky gut syndrome) and increase autoimmunity upon high exposure of stress and HPA axis activity. Intestinal microbiota determine the integrity of the BBB and can cause impairment leading to abnormal chemical membrane crossing and induced HPA axis exertion. A common stress-induced factor leading alterations of the gut microbiota and dysfunction of the gut barrier has been found to be caused by early-life stress events primarily examined in the context of physical and emotion abuse and neglect, sexual abuse, as well as childhood adversity such as dysfunctional family, school, and neighborhood environments and economic strain.[#References|[12]]][#References|[13]]] The further stimulation of the HPA axis leading to hyperactive exertion of the neural pathway and increased anxiety is both a cause and result of a dysfunctional gut microbiome ecosystem.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

[1] Cryan, J. F., O’Riordan, K. J., Cowan, C. S. M., Sandhu, K. V., Bastiaanssen, T. F. S., Boehme, M., Codagnone, M. G., Cussotto, S., Fulling, C., Golubeva, A. V., Guzzetta, K. E., Jaggar, M., Long-Smith, C. M., Lyte, J. M., Martin, J. A., Molinero-Perez, A., Moloney, G., Morelli, E., Morillas, E., … Dinan, T. G. (2019). The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiological Reviews, 99(4), 1877–2013. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00018.2018

[2] Simpson, C. A., Diaz-Arteche, C., Eliby, D., Schwartz, O. S., Simmons, J. G., & Cowan, C. S. M. (2021). The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression – A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943

[3] Chaplin, T. M., Gillham, J. E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2009). Gender, anxiety, and depressive symptoms. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29(2), 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608320125

[4] The comorbidity of anxiety and depression | nami: National alliance on mental illness. (n.d.). Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.nami.org/blogs/nami-blog/january-2018/the-comorbidity-of-anxiety-and-depression

[5] CDCTobaccoFree. (2022, September 14). Depression and anxiety. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/campaign/tips/diseases/Depression is more than just feeling down or having a bad day. When a sad mood lasts for a long time and interferes with normal, everyday functioning, you may be depressed.

[6] Penny M Kris-Etherton, Kristina S Petersen, Joseph R Hibbeln, Daniel Hurley, Valerie Kolick, Sevetra Peoples, Nancy Rodriguez, Gail Woodward-Lopez, Nutrition and behavioral health disorders: depression and anxiety, Nutrition Reviews, Volume 79, Issue 3, March 2021, Pages 247–260, https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa025

[7] Anxiety disorders—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 13, 2023, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anxiety/symptoms-causes/syc-20350961

[8] Goodwin, G. M. (2015). The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(3), 249–260. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4610610/

[9] McCarter, T. (2008). Depression overview. American Health & Drug Benefits, 1(3), 44–51. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4115320/

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2023, Kenyon College