Tuberculosis in Russian Prisons: Difference between revisions

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[1] ["Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis in Russia". www.scientificamerican.com/report.cfm?id=tuberculosis-in-russia. 5 Dec. 2009] | <br>[1] ["Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis in Russia". www.scientificamerican.com/report.cfm?id=tuberculosis-in-russia. 5 Dec. 2009]<br> | ||

[2] ["Tuberculosis-can the spread of this killer disease be halted?". Microbes and Diseases Fact file 1] | <br>[2] ["Tuberculosis-can the spread of this killer disease be halted?". Microbes and Diseases Fact file 1]<br> | ||

[3] [Richard Coker, Martin McKee, Rifat Atun, Boika Dimitrova, Ekaterina Dodonova, Sergei Kuznetsov, and Francis Drobniewski | <br>[3] [Richard Coker, Martin McKee, Rifat Atun, Boika Dimitrova, Ekaterina Dodonova, Sergei Kuznetsov, and Francis Drobniewski | ||

Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis in Russia: case-control study | Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis in Russia: case-control study | ||

BMJ, Jan 2006; 332: 85 - 87. ] | BMJ, Jan 2006; 332: 85 - 87. ]<br> | ||

[4] [Adverse reactions among patients being treated for MDR-TB in Tomsk, Russia. | <br>[4] [Adverse reactions among patients being treated for MDR-TB in Tomsk, Russia. | ||

S. S. Shin, A. D. Pasechnikov, I. Y. Gelmanova, G. G. Peremitin, A. K. Strelis, S. Mishustin, A. Barnashov, Y. Karpeichik, Y. G. Andreev, V. T. Golubchikova, T. P. Tonkel, G. V. Yanova, A. Yedilbayev, M. L. Rich, J. S. Mukherjee, J. J. Furin, S. Atwood, P. E. Farmer, and S. Keshavjee | S. S. Shin, A. D. Pasechnikov, I. Y. Gelmanova, G. G. Peremitin, A. K. Strelis, S. Mishustin, A. Barnashov, Y. Karpeichik, Y. G. Andreev, V. T. Golubchikova, T. P. Tonkel, G. V. Yanova, A. Yedilbayev, M. L. Rich, J. S. Mukherjee, J. J. Furin, S. Atwood, P. E. Farmer, and S. Keshavjee | ||

Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007 December; 11(12): 1314–1320.] | Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007 December; 11(12): 1314–1320.]<br> | ||

[5] [Rates of Latent Tuberculosis in Health Care Staff in Russia | <br>[5] [Rates of Latent Tuberculosis in Health Care Staff in Russia | ||

Francis Drobniewski, Yanina Balabanova, Elena Zakamova, Vladyslav Nikolayevskyy, and Ivan Fedorin | Francis Drobniewski, Yanina Balabanova, Elena Zakamova, Vladyslav Nikolayevskyy, and Ivan Fedorin | ||

PLoS Med. 2007 February; 4(2): e55. Published online 2007 February 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040055. | PLoS Med. 2007 February; 4(2): e55. Published online 2007 February 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040055. | ||

PMCID: PMC1796908] | PMCID: PMC1796908]<br> | ||

[6]["Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance". http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/9/06-038331-ab/en/index.html. 5 Dec. 2009] | <br>[6]["Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance". http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/9/06-038331-ab/en/index.html. 5 Dec. 2009]<br> | ||

[7][Eur J Public Health. 2007 Feb;17(1):98-103. Epub 2006 Jul 12. | <br>[7][Eur J Public Health. 2007 Feb;17(1):98-103. Epub 2006 Jul 12. | ||

Reform of tuberculosis control and DOTS within Russian public health systems: an ecological study. | Reform of tuberculosis control and DOTS within Russian public health systems: an ecological study. | ||

Marx FM, Atun RA, Jakubowiak W, McKee M, Coker RJ. | Marx FM, Atun RA, Jakubowiak W, McKee M, Coker RJ. | ||

Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London, UK.] | Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London, UK.]<br> | ||

Edited by student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/BIOL191_09/BIOL_191_Global_Health_Syllabus.htm BIOL 191 Microbiology], 2009, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | Edited by student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/BIOL191_09/BIOL_191_Global_Health_Syllabus.htm BIOL 191 Microbiology], 2009, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | ||

Revision as of 21:18, 17 December 2009

Introduction

Edited by: Christopher Murphy

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is considered one of the most deadly infectious diseases. Russia has experienced a steady rise in cases beginning with the collapse of the Soviet Union. One of the most conducive breeding grounds for tuberculosis in Russia has been prisons. However, prisoners are not the only ones that need to be concerned, the tuberculosis is likely to spread to the rest of society through released prisoners and prison and hospital workers. [1] Consequently, the condition of tuberculosis is a major public health concern for not only Russia but the entire world as globalization interconnects countries. Although the current conditions in Russia are not favorable efforts are being made to reduce the gravity of tuberculosis. TB spreads person to person via aerosol transmission when an infected person sneezes, coughs or talks. The bacteria last in the air for days and travel over great distances, making the disease extremely tenacious. For a successful infection, at least 10 cells of the bacteria need to reach the lungs' alveoli. Tuberculosis is aerobic and thus the lungs provide a conducive environment for infection due to the high levels of oxygen. Over the course a year a person with tuberculosis can infect 10-15 people. There are several stages to the development of tuberculosis. Latent tuberculosis indicates the existence of bacteria in the body but the bacteria has been suppressed by the immune system. Moreover, no infection has developed. If the immune system becomes compromised active(susceptible) tuberculosis develops. If treated improperly a relatively mild case can become multi-drug resistant (MDR) and/or extensively drug resistant(XDR). Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is resistant to first line drugs. Therefore, more powerful and more expensive second line drugs are needed. Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis is essentially impossible to treat.[2]

Humans have suffered heavily from this disease throughout history. During the "White Plague" of 17th and 18th centuries, tuberculosis was responsible for 25% of adult deaths and few people escaped infection. Over time tuberculosis began to disappear with the improvement of living conditions and the development of antibiotics. Yet today roughly 33% percent of the world's population has latent tuberculosis. The advent of tuberculosis was underscored by the World Health Organization's 1993 global emergency declaration concerning tuberculosis. This was in part due to a rise in multi-drug resistant TB as well as an increased number of AIDS cases.[2]

Why Tuberculosis is so prevalent in Russia

Tuberculosis is an opportunistic infection, exploiting compromised immune systems. Large populations, inadequate nutrition, constant stress, poor living conditions, the use of intravenous drugs, alcoholism and co-infections(HIV/AIDS) all contribute to compromised immune systems. Russia and its prisons, stressful and impoverished environments, are home to these factors. Severe penal codes and lack of funds have exacerbated these conditions. An example of the severity of the penal code is a prison sentence that resulted from the theft of a cell phone. Since approximately 33% of the world has latent tuberculosis, it is likely that when the prison populations increased in the 1990s many of the new inmates were carriers. Moreover, a large amount of people were quickly crowded together in extremely uncleanly conditions, contributing to uniquely high stress levels. Many prisoners' immune systems could no longer suppress the latent infection. Little has been done to improve the conditions in prisons, due to the stigma towards prisoners. The quarantine of prisoners is less than ideal as all the infected prisoners are sometimes housed together causing re-infection. However, occasionally recovering prisoners will be separated. [1]

The recent spike in cases may be attributed to the combined effect of the collapse of infrastructure in Russia after the fall of the Soviet Union and the release of prisoners who are inadequately treated for TB back into society. As a result of the collapse of Russian infrastructure the rates of alcoholism, unemployment, crime, incarceration and movement in and out of prison all increased significantly. Furthermore, health and social services ceased to exist only exacerbating the problem at hand. Diagnostic tests could not be afforded any more as well microscopes for sputum examination. Consequently, much of the treatment was ended prematurely leading to TB rates that topped the charts as the world's highest and MDR strains of Tuberculosis.[1]

The prisoners face very high risks of contraction as TB borders the epidemic threshold mark. Prisoners are 58 times likelier to contract tuberculosis than the average Russian citizen and are 28 times likelier to die from the disease. As of 1999, the Russian prison population neared 1.1 million prisoners, in which 1 in 11 prisoners had tuberculosis. As a consequence of sporadic treatment MDR strains have arisen affecting 20,000 prisoners. Through the 1990s crime waves caused prison populations to surge every now and then. Similarly, the amount of people being released and incarcerated numbered in the millions. As a result, many released prisoners have MDR strains because of inadequate treatment and spread it to the public. Figure 1. exemplifies the conditions in Russian prisons. Prisoners, separated from nurses by iron bars, line up for inoculation.

Russian prisons are considered "epidemiological pumps" for the rest of Russian society. For instance, after being cramped inside prisons, prisoners return home to equally small apartment blocs. During the winters, these unventilated apartments serve as breeding grounds for TB. Additionally, there is the risk of prison and hospital workers will becoming infected and transmitting the disease to the rest of society. [1]

Attempts of Fighting off Tuberculosis

History

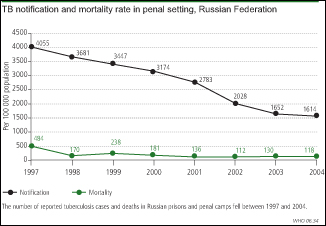

Due to the lack of funds Russia has continued to struggle with tuberculosis until recently. Russia had previously its satellites to produce antibiotics but with the collapse drugs and funding were both in short supply. The newly independent satellite republics no longer continued the barter trade with Russia for antibiotics.[1] In the late 1990s George Soros became a key benefactor to the treatment of tuberculosis. In addition, Medical Emergency Relief International and Partners in Health have done work in Russia to develop a new TB program which has alleviated some of the disease. Russia has also heavily relied on the Eli Lilly and Company Foundation and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria. The creation of the Green Light Committee, a drug procurement consortium, has been crucial to the fight against Tuberculosis. Green Light Committee is compromised of WHO, U.S. CDC, ngos and pharmaceutical firms. The effectiveness of this program is highlighted by the drop in cost of patient care. Previously, treatment cost $10,000 to $15,000 and currently runs around $3,000 to $4,000. Through this committee countries such as Russia can afford medication, including the more expensive second line drugs to treat MDR-TB. This was the direct consequence of purchase contracts and subsidies. The general condition of hospitals has improved with increased funding from organizations such as Global Fund. Improvements include new lab equipment such as airtight closets to house sputum and technology for culturing. The handling of cases has also changed for the better, those with TB are sent back to the barracks while MDR-TB prisoners are isolated in the hospitals, 6 to 8 prisoners to a room. The goal of the international organizations is to counsel, help develop an infrastructure and empower Russia to be self-reliant.[1] Figure 2 illustrates the success of treatment as the tuberculosis prevalence has decreased in prisons over time.

Unfortunately, the Health ministry has been hesitant to adopting the DOTS strategy. Partial lung surgery is the approved method of treatment in Russia despite the controversy this procedure warrants from the outside world. Some doctors have also been skeptical about DOTS and have adamantly continued their own methods. Contrary to the Health Ministry, many of the local doctors were fine with participating in the DOTS strategy, however, many of the pharmacies ran out of supplies-even first-line drugs where in short supply[1].

DOTS Strategy

The DOTS program has been implemented and is usually the strategy of choice. It is an daily procedure in which 4 antibiotics are taken orally for 6 to 9 months under the care of a health official. It was first believed in the 1940s that the drug streptomycin was the cure until it was discovered that tuberculosis mutates and that multiple drugs were necessary. The logic is based on statistics and probability, the drugs attack the tuberculosis in several different places simultaneously. Tuberculosis is slow growing, only reproducing once a day, resulting in a lengthy therapy session. One new idea of treatment is the pursue the strategy of directing more attention to MDR-TB than susceptible TB. This strategy has been adopted by Russia and many other former satellite republics that collectively form the Commonwealth of Independent States. It is hoped that this method will begin to be adopted by other countries around the world as well as help reach the 2015 goal of cutting the TB's global prevalence and mortality in half. Partners in Health developed this technique called DOTS Plus, in which all MDR-TB cases are treated, this has lead to a more extensive and intensive treatment. It is considered a bolder and more costly procedure. Local doctors were encouraged first in the prison system and then all throughout the region. This program takes up to two years and requires 6 to 8 drugs. MDR-TB and TB are similar in their capability to be lethal, the main difference is that MDR-TB is much harder to treat than TB. There is more and more agreement that MDR-TB should be the form of TB to be concentrated on because in treating MDR-TB then TB will also be treated.[1]

The most important factor in a successful recovery from tuberculosis is the treatment is completed entirely. There are two main reasons that this does not occur sometimes. Generally, during the beginning months the majority of the tuberculosis bacteria is killed and the symptoms go away. Many patients stop taking the medications falsely believing that they are cured. However, some tuberculosis survives and makes a waxy coat and buries away in the lung. [2] Of the bacteria that does survive, there are mutant strains that are resistant to the drugs. When treatment is terminated early, these strains take over causing the tuberculosis to be more virulent. Additionally, patients may object to continuing therapy is that the DOTS drugs have adverse side effects such as hallucinations, nightmares and vomiting. [1]

Tuberculosis Studies

Study 1

Some of the most convincing evidence of the general risk factors of Tuberculosis and varying importance in Russia comes from the study "Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis in Russia: case-control". The study was a case-control study in which existing cases of a medical condition are compared with a control group of the same number and similar composition. The goal of the study was to find and rank the risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis. The leading risk factors were low accumulated wealth, financial insecurity, consumption of unpasteurized milk, diabetes, living with a relative with tuberculosis, unemployment, overcrowded living conditions, illicit drug use and incarceration. Of these leading risk factors when considering the amount of exposure, consumption of unpasteurized milk and unemployment.[3]

Study 2

In the study "Rates of latent tuberculosis in health care staff in Russia" the goal was to find individuals with latent tuberculosis infections and the rates of infection to treat through chemo prophylaxis and cross-infection strategies. In a cross sectional study, risk of tb was compared between unexposed students, medical students, primary health care providers and TB hospital health providers. Results showed that the amount of exposure could be linked to the likelihood of having LTBI. Primary health care providers were more likely to have TB(39.1% or 90/230) than students (8.7% or 32/368) and TB hospital health providers (46.9% or 45/96) were more likely to have TB than the primary health care providers (29.3% or 34/115). In addition, TB laboratory workers also had high levels of tuberculosis (61.1% or 11/18). From the results it can be concluded that TB Health Care Workers are have the highest risk and precautionary measures need to be taken.[5]

Study 3

A major concern for using second line drugs to treat MDR Tuberculosis is that many of them cause adverse reactions because of their toxicity. Through a retrospective case series "Adverse Reactions among patients being treated for MDR-TB in Tomsk, Russia" explored this question. Of the 244 cases 76% were cured, 6.6 % failed, 4.9 % died and 11.5 % defaulted. 73.3% of all cases showed adverse reactions, 74.8% in patients that adhered (at minimum took 80% of prescribed doses) and 59.1% of those that did not adhere. It was found that these adverse reactions varied on the amount of drugs taken but had no effect on the outcome. [4]

Summary of Studies

Each of these studies addresses a specific concern regarding tuberculosis. The first study outlined the general risk factors for tuberculosis. In the second study, the risk of contracting tuberculosis for health care workers is examined. The third study investigates the question of whether or not second line drugs inherent qualities jeopardize the success of a patient's outcome.

Conclusion

There has been success in treating tuberculosis in Russia. The prisoner population needs to be a continued area of focus since this demographic is at a higher risk than others. With international help along with internal effort Russia will begin to be able to eradicate tuberculosis and improve its standard of living. In the mean time great care must be taken with the DOTS procedure and health care personnel exposure so that tuberculosis in Russia will remain under control.

References

[1] ["Multidrug Resistant Tuberculosis in Russia". www.scientificamerican.com/report.cfm?id=tuberculosis-in-russia. 5 Dec. 2009]

[2] ["Tuberculosis-can the spread of this killer disease be halted?". Microbes and Diseases Fact file 1]

[3] [Richard Coker, Martin McKee, Rifat Atun, Boika Dimitrova, Ekaterina Dodonova, Sergei Kuznetsov, and Francis Drobniewski

Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis in Russia: case-control study

BMJ, Jan 2006; 332: 85 - 87. ]

[4] [Adverse reactions among patients being treated for MDR-TB in Tomsk, Russia.

S. S. Shin, A. D. Pasechnikov, I. Y. Gelmanova, G. G. Peremitin, A. K. Strelis, S. Mishustin, A. Barnashov, Y. Karpeichik, Y. G. Andreev, V. T. Golubchikova, T. P. Tonkel, G. V. Yanova, A. Yedilbayev, M. L. Rich, J. S. Mukherjee, J. J. Furin, S. Atwood, P. E. Farmer, and S. Keshavjee

Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007 December; 11(12): 1314–1320.]

[5] [Rates of Latent Tuberculosis in Health Care Staff in Russia

Francis Drobniewski, Yanina Balabanova, Elena Zakamova, Vladyslav Nikolayevskyy, and Ivan Fedorin

PLoS Med. 2007 February; 4(2): e55. Published online 2007 February 13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040055.

PMCID: PMC1796908]

[6]["Barriers to successful tuberculosis treatment in Tomsk, Russian Federation: non-adherence, default and the acquisition of multidrug resistance". http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/9/06-038331-ab/en/index.html. 5 Dec. 2009]

[7][Eur J Public Health. 2007 Feb;17(1):98-103. Epub 2006 Jul 12.

Reform of tuberculosis control and DOTS within Russian public health systems: an ecological study.

Marx FM, Atun RA, Jakubowiak W, McKee M, Coker RJ.

Department of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Keppel Street, London, UK.]

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 191 Microbiology, 2009, Kenyon College.