Type III CRISPR Systems

Introduction

By Amir Brivanlou, 21'

Clustered Regularly Spaced Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) are DNA sequences found throughout prokaryotes and archaea that, in conjunction with a variety of Cas enzymes, are responsible for anti-phage defense mechanisms[1]. Generally, foreign bacteriophage DNA is recognized by the enzymes Cas1 and Cas2 and incorporated into the CRISPR array within the host organisms’ genome. These portions of bacteriophage DNA are known as spacers. These spacers can then be transcribed into RNA and used as guides to direct the cleavage of future phage invaders [2].

There exists a tremendous diversity of CRISPR systems, there are two distinct classes of CRISPR systems each with three types of CRISPR/Cas systems containing their own specialized Cas enzymes and modes of action [3]. The type II CRISPR system, encoding a Cas9 endonuclease, is the best characterized of the CRISPR systems due to its prevalence as a gene-editing tool. The discovery and subsequent characterization of type II CRISPR systems and their use in gene editing recently resulted in the Nobel prize being awarded to Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier [4].

While most CRISPR systems target DNA, type III CRISPR-Cas immunity has been shown to target both DNA and RNA, making them of special interest [5]. Additionally, type III systems are thought to be the most ancient of the CRISPR systems as Cas10, the signature endonuclease of type III systems, was likely the original effector in bacteria and archaea [6]. Type III CRISPR systems are thought to be the most complex of the CRISPR types, and in the following article I hope to highlight the current knowledge on spacer acquisition, biogenesis, and interference in type III CRISPR systems.

Class I and Class II CRISPR systems

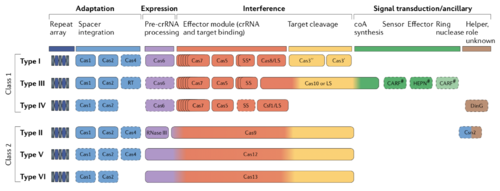

There exist two distinct classes of CRISPR systems in bacteria and archaea. The first class contains types I, III, and IV, while the second includes types II, V, and VI. The key differences between these classes lie in the organization of the effector module. Type I systems possess a multi-protein crRNA-binding complex that functions together to target and cleave phage DNA. This heterogeneous effector complex in class I systems is functionally analogous to the Cas9, Cas12, or Cas13 effector modules in Class 2 systems which bind crRNAs, target phage DNA, and cleave it.

All CRISPR/Cas systems, however, must possess proteins that can execute the following four functions. The first fundamental function is spacer adaptation, or the process by which DNA sequences derived from cleaved prophage are incorporated into the CRISPR array. These genes usually encode an integrase, while Type III systems also often include an RT and integrase. The second function all CRISPR systems must possess is expression, which refers to the processing of the guide crRNAs, which are transcribed sequences of prophage DNA used to target future phage invaders. These crRNAs require extensive processing before they can be loaded into a nuclease and direct cleavage. Cas6 is the primary crRNA processor in Class I systems, while RNAse III or the endonuclease itself processes crRNAs in Class II systems. The third function of CRISPR systems is interference. Interference is the directed cleavage of prophage DNA. As previously stated, interference is executed by a single endonuclease in Class II systems, while several enzymes mediate class I system interference. Finally, the fourth function is loosely defined as signal transduction, these are helper proteins that are loosely linked to CRISPR immunity which are involved in metabolic regulation and general bacterial function. Despite common fundamental functions, there is tremendous diversity in how different CRISPR/Cas types guard the cell against phage. This article will focus on how Type III CRISPR systems execute these fundamental functions in unique ways.

Type III Adaptation

Bacteria and prophage are often engaged in a heated arms race. Sequences of the invading phage genome are incorporated into CRISPR arrays through a process known as adaptation. While these sequences may protect the host for several generations, mutation of phage DNA coupled with natural selection forces bacteria to continuously acquire and incorporate novel spacers (Barrangou et al., 2007).

Most CRISPR systems utilize the tandem pair of Cas1/Cas2 enzymes to bind and integrate prophage DNA, usually having been processed by restriction enzymes (CITE), although plasmid derived spacers and even spacers derived from the host’s genome have been detected (Nuñez et al., 2015; Stern et al., 2010). Both Cas1 and Cas2 have been shown to associate with Type III systems in vivo; however, direct evidence of Cas1/Cas2 mediated spacer integration has yet to be seen. Additionally, spacers in type I and type II systems always begin with proto-spacer adjacent motifs (PAM) sequences which, canonically, is 5'-NGG-3 (Mojica et al., 2009); however, acquisition of spacers in Type III systems does not seem to be dependent on PAM motifs, indicating that acquisition may be random (Artamonova et al., 2020).

Type III systems also uniquely encode a Cas1-RT fusion protein which can integrate RNA sequences into the CRISPR array. This Cas1-RT fusion is encoded by a very rare Type III-D system found in the marine bacterium Marinomonas mediterranea (Silas et al., 2016). Type III adaptation was first characterized in this system, and it remains the only example of detection of in vivo type III adaptation (Peyson et al., 2016). Marinomonas mediterranea is gram-negative bacteria initially isolated from the Mediterranean. This study showed that when the RT-Cas1 fusion was overexpressed in Marinomonas mediterranea, spacer acquisition was detected by gel electrophoresis.Additionally, these spacers were derived from phage DNA rather than from highly transcribed regions of the host genome. The authors showed, through mutagenesis, that when the RT domain was knocked out, the association between highly transcribed sequences and spacer acquisition was abolished. The Type III CRISPR system from Marimonas was then placed onto a plasmid and ectopically expressed in E.Coli cells to further investigate the mechanism of spacer acquisition. When the cells were supplied with synthetic oligos, both RNA and, strikingly, DNA was shown to be incorporated into the plasmid-bound Type-III CRISPR array. RNA spacer integration was dependent on the RT domain, while DNA spacer acquisition was not. The RNA was incorporated in both the sense and antisense directions, meaning that some 50% of spacers may be completely useless. These results provide a framework for RNA spacer integration in type III systems. As we will explain, Type III systems target actively transcribed DNA, so the incorporation of RNA spacers allows for the targeting of genes that are actively transcribed. Crucially, these results were obtained by overexpressing type III systems, and none of the spacers were incorporated from invading phage DNA.

Additionally, only a tiny subset of bacterium (~8%)(Sontheimer and Marraffini et al., 2016) contain this Cas1-RT fusion, so integration of DNA spacers is the far more common form of adaptive immunity in type III systems across prokaryotes. We can see the overall view of both RNA and DNA spacer acquisition in figure X. More work clearly needs to be done to identify the mechanisms of DNA spacer acquisition in vivo.

Type III crRNA Biogenesis

In order to confer immunity, the CRISPR array must be transcribed and processed to allow for spacer integration and targeting of Cas endonucleases. Once transcribed, spacers are referred to as CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs). In type III CRISPR systems, the entire CRISPR array is transcribed into a single long pre-RNA (Marraffini et al., 2016). Cas6, the same endonuclease involved in type II crRNA biogenesis, recognizes stem loops formed by the palindromic sequences which flank the spacers. Cas6 cleaves 8nt upstream of the spacer sequences interrupting the upstream stem-loop structures while retaining the downstream and freeing the nascent crRNA (Carte et al. 2008) (Figure X). Crucially, these stem loops are necessary for proper recognition and processing of the pre-crRNA by Cas6 to eliminate the stem-loop structures resulting in nonfunctional crRNAs (Hatoum-Aslan et al. 2011). The intermediate crRNA is then delivered to the Cas10 complex by the endonuclease Cas6 (Sokolowski et al., 2014). Cas6 proteins fail to co-purify with any of the other Cas enzymes; therefore, their function is thought to be entirely independent (Charpentier et al., 2015). Once loaded into the Cas 10 complex, the crRNAs are furthest processed, and a non-Cas6 endonuclease trims the stem-loops on the 3’ end. Additionally, Cas10 complexes have frequently been purified with crRNA which differ in size. These crRNAs vary by lengths of 6, indicating that trimming of a series of 6nt from the 3’ end of the crRNAs occurs, hypothetically (Charpetier et al., 2015) to increase spacer diversity and lower the homology burden to the invading phage’s genome. Mature crRNAs are usually approximately 50nt in length. Once processed, the crRNA/Cas10 complex can target ssRNA in Type III-A systems and ssRNA and ssDNA type III-B systems. Additionally, the Csm2 and Csm5 proteins are necessary for crRNA maturation in Type III-A systems; however, their exact roles in said maturation remain unknown (Hatoum-Aslan et al., 2011).

Type III Effector Complex Structure

Type III interference was a long-standing conundrum as Type III-A systems, initially identified in Staphylococcus aureus, were thought to exclusively target DNA while Type III-B systems, originally identified in the hyperthermophilic archaea Pyrococcus furiosus, exclusively target RNA. Recently, it has been shown that all type III CRISPR systems are RNases and target RNA-activated DNA nucleases (Tamulatis et al., 2017). The exact mechanism of this unique RNAse and DNase activity will be explored in this section.

Type III interference is mediated by a multi-subunit protein complex made up of at least five Cas proteins bound to a guide crRNA (Marraffini et al., 2016). Type III-A/D possesses a “Csm” effector complex, and Type III-B/C systems possess a “Cmr” effector complex that differs in their protein subunits. These Csm/Cmr complexes are the effectors of CRISPR/Cas immunity, possessing the targeting and nuclease activities of the type III system. The signature Cas10 nuclease associates with is a part of these complexes. While each subtype's subunits differ, the two complexes share distinctly similar overall structures (Figure X), stoichiometry, and general function (Peyson et al., 2016). The 5’ end of the complex is where the nuclease Cas10 associates with the Cas5-family proteins Csm4 or Cmr4. These Cas5 family proteins bind a region of the crRNA to know as the 5’ handle. This handle is made up of an 8nt stretch remaining from the palindromic sequence of the CRISPR array; it is believed to be involved in autoimmune avoidance; however, the exact mechanism of this avoidance remains to be elucidated (Kazlauskian et al., 2016). The major filaments are the backbones of the complexes (Tamulatis et al. 2017) and are formed by a single Csm4/Cmr3 and a variable number of Csm3/Cmr4 proteins depending on the length of the mature crRNA. The minor filaments are composed of small Csm2/Cmr5 proteins along with the C-terminal D4 domain of Cas10 (Figure X). The major filament is largely responsible for crRNA binding while the minor filament binds the target strand, which is to be degraded (Samai et al., 2015). The presence of a target RNA causes the Csm2/Cmr5 proteins to reveal the crRNA sequence and allow it to make complementary base pairs with its target (Taylor et al., 2015). As one would expect, sequence homology between the crRNA and target RNA is necessary for degradation to occur. While the Csm2/Cmr5 proteins facilitate binding to the target RNA, the Csm3/Cmr4 peptides cleave the target RNA after binding into 6nt fragments, rendering it non-functional.

Type III DNA/RNA Interference

As previously mentioned, the mechanism and types of substrates of type III substrates were puzzling for a long time. It was proposed that Csm effectors targeted DNA while Cmr targeted RNA exclusively. This model had to be rejected after studies in the archaeal Sulfolobus islandicus showed that that type III-B Cmr effectors are capable of transcriptionally dependent DNA degradation, meaning that active transcription was required for DNA degradation (Deng et al., 2013). This striking co-transcriptional degradation of target RNA and DNA is unique to all type III CRISPR systems. Furthermore, other studies showed that mutations in bacteriophage promoters that inactivate the crRNA targets transcription are immune to type III systems. This study also showed that crRNAs must be complementary to the target, and therefore the non-template DNA strand to confer immunity (Goldberg et al., 2014). A final set of studies showed that while homology between the crRNA and target RNA was necessary, binding of the effector to its target transcript triggered the degradation of ssDNA at the transcription bubble regardless of DNA homology (Estrella et al., 2016). Cas10 was also shown to be the source of this ssDNA cleavage; however, the exact Cas10 domain that performs this activity has yet to be identified. This series of studies led to the formulation of a unified mechanism for type III interference, reviewed here (Peyson et al., 2016; Tamulatis et al., 2017).

Type III interference begins with a mature Cmr/Csm effector complex bound to a processed crRNA. Transcription of a phage gene homologous to the crRNA in the effector complex triggers Cmr/Csm localization to the transcription complex. The Type III effector complex, bound to the nascent phage RNA transcript, has both its DNA and RNA nuclease functions activated, and the ssDNA at the transcription site is a prime location for cleavage by Cas10. The nascent RNA, as well, is cleaved by the Csm3/Cmr4 units of the effector complex. Type III immunity, however, leaves open the possibility for autoimmune degradation of host DNA as the DNAse activity conferred by Cas10 is not sequence-specific. While cleavage of the crRNA bound target RNA is thought to protect against this autoimmunity (Estrella et al., 2016), there are other fail-safe mechanisms in place to stop the host from attacking its own genome.

Protections against Autoimmunity

Consequences of Type III Immunity

References

- ↑ https://science.sciencemag.org/content/315/5819/1709/tab-pdf RODOLPHE BARRANGOU, CHRISTOPHE FREMAUX, HÉLÈNE DEVEAU, MELISSA RICHARDS, PATRICK BOYAVAL, SYLVAIN MOINEAU, DENNIS A. ROMERO, PHILIPPE HORVATH. "CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes" (2007) Science, 1709-1712]

- ↑ Jackson, Simon A. McKenzie Rebecca E. Fagerlund, Robert D. Kieper, Sebastian N. Fineran, Peter C. Brouns, Stan J. J. “CRISPR-Cas: Adapting to change” 2017, 10.1126/science.aal5056.

- ↑ [https://www.nature.com/articles/s41579-019-0299 Makarova, K.S., Wolf, Y.I., Iranzo, J. et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat Rev Microbiol 18, 67–83 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-019-0299-x

- ↑

- ↑ Poulami Samai, Nora Pyenson, Wenyan Jiang, Gregory W. Goldberg, Asma Hatoum-Aslan, Luciano A. Marraffini “Co-transcriptional DNA and RNA Cleavage during Type III CRISPR-Cas Immunity”, 2015, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.027.

- ↑ Mohanraju, Prarthana. Makarova, Kira S. Zetsche, Bernd. Zhang, Feng. Koonin, Eugene V. van der Oost, John “Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems”, 2016, 10.1126/science.aad5147