User:Baileyk: Difference between revisions

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

<br>By [Kyle Bailey]<br> | <br>By [Kyle Bailey]<br> | ||

[[Image:geo.jpg|thumb|300px|right|http://ijs.sgmjournals.org/content/49/4/1615.full.pdf+html]] | [[Image:geo.jpg|thumb|300px|right|http://ijs.sgmjournals.org/content/49/4/1615.full.pdf+html]] | ||

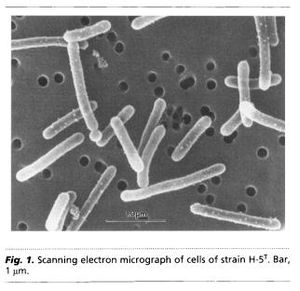

Geothrix fermentans are non-motile rod-shaped bacteria. Due to the Greek origin of its name “Geo” meaning earth and “thrix” pertaining to hair, G. fermentans are sometimes described as hair like organisms from the earth. They can occur either singly or in chain links. Their cell size is around 0.1 µm in diameter and between 2-3 µm in length (Figure 1.) (Coates et al., 1999). They are gram-negative bacteria that can be grown on and identified by MacConkey agar plates as they will appear pink in color due to a thinner peptidoglycan cell wall than in gram-positive bacteria. G . fermentans do not produce spores during their reproductive cycle. The optimal growth temperature is at 35°C and there has been no indication of growth below 25°C. Geothrix fermentans were discovered in 1999 at Hanahan, SC in the United States. By using 16S rDNA, we have determined that the closest identifiable bacterial relative of G. fermentans is Holophaga foetida with a 94.3% sequence identity (Slonczewski and Foster., 2010). | |||

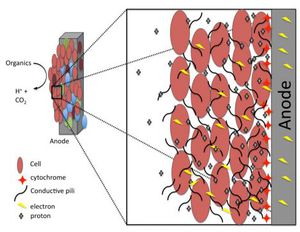

Fermentans are commonly associated with aquatic sediments such as aquifers because they are anaerobic bacterium and aquifers provide an ideal environment for them to not only survive but flourish. G.fermentans are a member of the acidobacterium phylum a rather recently devised phylum that includes several bacteria that serve an important role as contributors to many different kinds of environmental niches. Other acidobacterium similar to Geothrix fermentans include Halophaga foetida, Bryobacter aggregatus, and Acanthopleuribacter pedis. Fermentans are physiologically associated with Geobacteraceae because they both are strict anaerobes that conserve energy to support growth by oxidizing organic acids into CO₂ by using Fe (III) oxides as their primary electron acceptor; however, they are phylogenetically distinct from one another (Nevin and Lovely., 2002). Fermentans are one of only a few species of freshwater cultivable bacteria that are capable of metal respiration using the electron acceptor Fe (III) oxide. All cells that are grown using Fe (III) oxide or fumarate as an electron acceptor contain c-type cytochromes (Coates et al., 1999). | |||

As an anaerobic chemorganotroph, fermentans are well-known for their ability to use Iron oxides as well as various other elements as electron acceptors such as Mn (IV), nitrate, fumarate, and the humic acid analog 2, 6 anthraquinone disulfonate, or it can be grown fermentatively with intermediates from the citric or Calvin cycle (Nevin and Lovely, 2002). The H-5 Geothrix strain for example (the first strain discovered in 1999) is also known for its ability to use several different organic compounds as electron donors such as acetate, propionate, lactate, palmitate, succinate and fumerate; however, it should be noted that Fe (III) should be the electron acceptor in this particular case (Coales et al., 1999). When aquifers become polluted such as in petroleum-contaminated aquifers, Geothrix become an ideal organism to thrive in these environments because they can use these minerals as electron donors and acceptors to immobilize environmentally harmful radioactive metals such as uranium, technetium, and cobalt. By using minerals such as Fe (III) fermentans are able to conserve energy to support growth by coupling the oxidation of organic compounds (Coates et al., 1999). This idea has led to an increase in knowledge for a better understanding of geochemical cycling of metals within the environment. | |||

==Metal Respiration== | ==Metal Respiration== | ||

Revision as of 03:08, 25 April 2013

Introduction

By [Kyle Bailey]

Geothrix fermentans are non-motile rod-shaped bacteria. Due to the Greek origin of its name “Geo” meaning earth and “thrix” pertaining to hair, G. fermentans are sometimes described as hair like organisms from the earth. They can occur either singly or in chain links. Their cell size is around 0.1 µm in diameter and between 2-3 µm in length (Figure 1.) (Coates et al., 1999). They are gram-negative bacteria that can be grown on and identified by MacConkey agar plates as they will appear pink in color due to a thinner peptidoglycan cell wall than in gram-positive bacteria. G . fermentans do not produce spores during their reproductive cycle. The optimal growth temperature is at 35°C and there has been no indication of growth below 25°C. Geothrix fermentans were discovered in 1999 at Hanahan, SC in the United States. By using 16S rDNA, we have determined that the closest identifiable bacterial relative of G. fermentans is Holophaga foetida with a 94.3% sequence identity (Slonczewski and Foster., 2010). Fermentans are commonly associated with aquatic sediments such as aquifers because they are anaerobic bacterium and aquifers provide an ideal environment for them to not only survive but flourish. G.fermentans are a member of the acidobacterium phylum a rather recently devised phylum that includes several bacteria that serve an important role as contributors to many different kinds of environmental niches. Other acidobacterium similar to Geothrix fermentans include Halophaga foetida, Bryobacter aggregatus, and Acanthopleuribacter pedis. Fermentans are physiologically associated with Geobacteraceae because they both are strict anaerobes that conserve energy to support growth by oxidizing organic acids into CO₂ by using Fe (III) oxides as their primary electron acceptor; however, they are phylogenetically distinct from one another (Nevin and Lovely., 2002). Fermentans are one of only a few species of freshwater cultivable bacteria that are capable of metal respiration using the electron acceptor Fe (III) oxide. All cells that are grown using Fe (III) oxide or fumarate as an electron acceptor contain c-type cytochromes (Coates et al., 1999). As an anaerobic chemorganotroph, fermentans are well-known for their ability to use Iron oxides as well as various other elements as electron acceptors such as Mn (IV), nitrate, fumarate, and the humic acid analog 2, 6 anthraquinone disulfonate, or it can be grown fermentatively with intermediates from the citric or Calvin cycle (Nevin and Lovely, 2002). The H-5 Geothrix strain for example (the first strain discovered in 1999) is also known for its ability to use several different organic compounds as electron donors such as acetate, propionate, lactate, palmitate, succinate and fumerate; however, it should be noted that Fe (III) should be the electron acceptor in this particular case (Coales et al., 1999). When aquifers become polluted such as in petroleum-contaminated aquifers, Geothrix become an ideal organism to thrive in these environments because they can use these minerals as electron donors and acceptors to immobilize environmentally harmful radioactive metals such as uranium, technetium, and cobalt. By using minerals such as Fe (III) fermentans are able to conserve energy to support growth by coupling the oxidation of organic compounds (Coates et al., 1999). This idea has led to an increase in knowledge for a better understanding of geochemical cycling of metals within the environment.

Metal Respiration

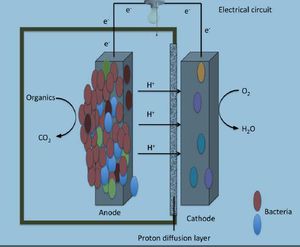

Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC)

Conclusion

Overall text length at least 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

5. [Yusoff, Mohd Zulkhairi Mohd, Anyi Hu, Cuijie Feng, Toshinari Maeda, Yoshihito Shirai, Yoshihito Shirai, et al. "Influence of pretreated activated sludge for electricity generation in microbial fuel cell application." Bioresource Technology. (2013)]

6. [Slonczewski, Joan, and John W. Foster. Microbiology an evolving science. 2nd. ed. New York: W.W Norton & Company, Inc., 2010. 1-1100.]

7. [Kyrpides, Nikos (September 23, 2011). "Geothrix fermentans DSM 14018". Doe Joint Genome Institute. Retrieved October 26, 2012]

8. [Liu, Joanne K.; Mehta-Kolte, Misha; Bond, Daniel R. "Expression and purification of GxcA, a c-type cytochrome involved in metal respiration by the bacterium Geothrix fermentans". University of Minnesota. Retrieved October 25, 2012]

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2011, Kenyon College.