User:Synthetic Biology: Synthesizing Petroleum Replica Fuel

Introduction

The field of synthetic biology combines hierarchical design strategies derived from electrical and mechanical engineering with genetic manipulations of microorganisms to generate artificial enzymatic pathways[1]. Strategies begin with an initial examination of the basic set of biological building blocks needed to develop systems of increasing complexity to enhance specific cellular outputs[2]. Researchers can design and implement unique synthetic pathways, selecting from an expansive array of microbial enzymes[1]. Synthetic fuels must share similar chemical components as retail transport fuels which are composed of hydrocarbons (n-alkanes) of variable length, branched hydrocarbons (iso-alkanes), and unsaturated hydrocarbons (n-alkenes)[3]. Designing and generating a microbial system aimed at synthesizing components of identical composition to petroleum fuel, eliminates several restricting factors limiting the success of alternative biofuels[3]. [1] [2] [3].

Current Species

There are three officially recognized Ignicoccus species: Ignicoccus hospitalis , Ignicoccus pacificus and Ignicoccus islandicus . The three species were initially identified by 16S rRNA gene analysis from the hydrothermal vent samples obtained from Kolbeinsey Ridge and the coast of Mexico[1] . All three species have been characterized as hyperthermophiles that are also obligate anaerobes which explains the presence of Ignicoccus species near hydrothermal vents[1] . None of the members of the Ignicoccus genus have been found to be [1] pathogenic to humans. [1] [2 [3] .

Morphology

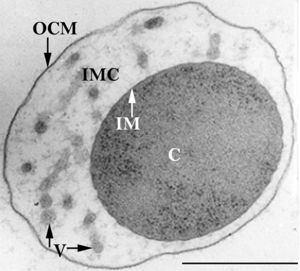

The members of the Ignicoccus genus are motile irregular coccoid cells that range in diameter from 1 to 3 µm. The motility observed is due to the presence of flagella, but unfortunately the polarity of the flagella is not yet fully elucidated. They are known to have an outer-membrane but no S-layer. This is a novel characteristic for these Archaea becauseIgnicoccus are the only known Archaea that have been shown to possess an outer-membrane[2] [10] .

Outer-Membrane

The outer-membrane of Ignicoccus species was found to be composed of various derivatives of the typical lipid archaeol, including the derivative known as caldarchaeol [5] . The outer-membrane is dominated by a pore composed of the Imp1227 protein (Ignicoccus outer membrane protein 1227). The Imp1227 protein forms a large nonamer ring with a predicted pore size of 2nm[7] .

Metabolism

Ignicoccus species are chemolithoautotrophs that use molecular hydrogen as the inorganic electron donor and elemental sulphur as the inorganic terminal electron acceptor[1] . The reduction of the elemental sulphur results in the production of hydrogen sulphide gas.

Ignicoccus are autotrophs in that they fix their own carbon dioxide into organic molecules. The carbon dioxide fixation process they use is a novel process called a dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon assimilation cycle that involves 14 different enzymes[8] .

Members of the Ignicoccus genus are able to use ammonium as a nitrogen source.

Growth Conditions

Because members of the Ignicoccus genus are hyperthermophiles and obligate anaerobes, it is not surprising that their growth conditions are very complex. They are grown in a liquid medium known as ½ SME Ignicoccus which is a solution of synthetic sea water which is then made anaerobic.

Grown in this media at their optimal growth temperature of 90C, the members of the Ignicoccus genus typically reach a cell density of ~4x107cells/mL[1] .

The addition of yeast extract to the ½ SME media has been shown to stimulate the growth and increase maximum cell density achieved. The mechanism by which this is achieved is not known[1] .

Symbiosis

Ignicoccus hospitalis is the only member of the genus Ignicoccus that has been shown to have an extensive symbiotic relationship with another organism.

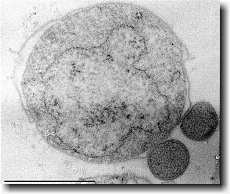

Ignicoccus hospitalis has been shown to engage in symbiosis with Nanoarchaeum equitans . Nanoarchaeum equitans is a very small coccoid species with a cell diameter of 0.4 µm[9] . Genome analysis has provided much of the known information about this species.

To further complicate the symbiotic relationship between both species, it’s been observed that the presence of Nanoarchaeum equitans on the surface of Ignicoccus hospitalis somehow inhibits the cell replication of Ignicoccus hospitalis . How or why this occurs has not yet been elucidated[3] .

Nanoarchaeum equitans

Nanoarchaeum equitans has the smallest non-viral genome ever sequenced at 491kb[9] . Analysis of the genome sequence indicates that 95% of the predicted proteins and stable RNA molecules are somehow involved in repair and replication of the cell and its genome[3] .

Analysis of the genome also showed that Nanoarchaeum equitans lacks nearly all genes known to be required in amino acid, nucleotide, cofactor and lipid metabolism. This is partially supported by the evidence that Nanoarchaeum equitans has been shown to derive its cell membrane from its host Ignicoccus hospitalis cell membrane. The direct contact observed between Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis is hypothesized to form a pore between the two organisms in order to exchange metabolites or substrates (likely from Ignicoccus hospitalis towards Nanoarchaeum equitans due to the parasitic relationship). The exchange of periplasmic vesicles is not thought to be involved in metabolite or substrate exchange despite the presence of vesicles in the periplasm of Ignicoccus hospitalis .

These analyses of the Nanoarchaeum equitans genome support the fact of the extensive symbiotic relationship between Nanoarchaeum equitans and Ignicoccus hospitalis. However, it has not yet been proven that it is a strictly parasitic relationship and further research may prove that there is a commensal relationship between the two species.

References

(1) Chiarabelli C, Stano P, Anella F, Carrara P, Luisi PL. Approaches to chemical synthetic biology. FEBS Letters. 2012

(2) Pleiss J. The promise of synthetic biology. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2006;73:735-739.

(3) Howard, T. P., Aves, S. J., Love, J., Middelhaufe, S., Moore, K., Edner, C., Smirnoff, N. (2013). Synthesis of customized petroleum-replica fuel molecules by targeted modification of free fatty acid pools in escherichia coli. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America,110(19), 7636.

(4) Lessard JC. Molecular cloning. Methods in enzymology. 2013;529:85.

(5) Tefferi A. Genomics Basics: DNA Structure, Gene Expression, Cloning, Genetic Mapping, and Molecular Tests. Seminars in Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia. 2006;10:282-290.

(6) Das D, Eser BE, Han J, Sciore A, Marsh ENG (2011) Oxygen-independent decarbonylation of aldehydes by cyanobacterial aldehyde decarbonylase: A new reaction of diiron enzymes. Angew Chem Int Ed 50:7148–7152

(7) Winson MK, Swift S, Hill PJ, et al. Engineering the luxCDABE genes from Photorhabdus luminescens to provide a bioluminescent reporter for constitutive and promoter probe plasmids and mini-Tn5 constructs. FEMS microbiology letters. 1998;163:193-202.

(8) Choi KH, Heath RJ, Rock CO (2000) β-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase III (FabH) is a determining factor in branched-chain fatty acid biosynthesis.J Bacteriol 182(2):365–370.

(9) Namba Y, Yoshizawa K, Ejima A, Hayashi T, Kaneda T. Coenzyme A- and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent branched chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase. I. Purification and properties of the enzyme from Bacillus subtilis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1969;244:4437.

(10) International Energy Agency (2011) Key World Statistics (Paris, France).

(11) Yuksel F, Yuksel B (2004) The use of ethanol-gasoline blend as a fuel in an SI engine. Renew Energy 29:1181–1191.

(12) National Renewable Energy Laboratory (2009) Biodiesel Handling and User Guide (Oak Ridge, TN: US Department of Commerce), 4th Ed.