West Nile Virus in Birds: Difference between revisions

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

==Host Factors | ==Host Factors== | ||

There is little evidence about why bird species are affected by West Nile Viruses differently. Some speculation and study points to life-style differences, such as breeding systems and geographic spread. Other differences may arise from immune-response capabilities and genetics. | |||

====Geography==== | ====Geography==== | ||

==== | [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phylogenetics Phylogenetically] related, geographically divergent species have been shown to be differently affected by West Nile Virus infection. Thus, their geographic spread is thought to influence their susceptibility. More southern-living species may acquire [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cross-reactivity cross-reactive] immunologic protection because they are more frequently exposed to mosquito born Flaviviridae infections. [xiiii] | ||

====Breeding Systems==== | |||

====Immunity/Genetics==== | ====Immunity/Genetics==== | ||

Chickens! | Chickens! | ||

Revision as of 04:07, 11 March 2014

West Nile Virus, of the family Flaviviridae, is a zoonotic disease that infects many species, including humans, throughout the world. Birds are the virus’s primary natural reservoir, where they act as an amplifier host. However, their host competency (their ability to perpetuate the virus' development and spread) and response to infection varies between species; they can have diverging viral loads, viremia, viral shedding, clinical signs, and morbidity. Many factors may affect a particular organism and/or species’ susceptibility and response to infection, including their immune-response capabilities, previous immunities, breeding systems, genetics, geographic spread, and stress levels. Overall, birds vary widely in how they are affected by West Nile Virus.

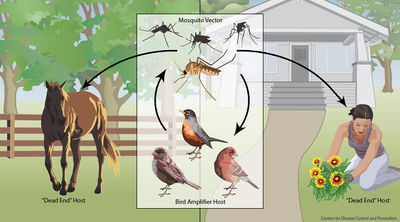

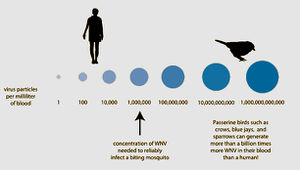

Most mammals, including horses and humans, are “dead-end” hosts for West Nile Virus, as, after infection, the virus does highly concentrate enough in the blood to then be spread to insect vectors. Many bird species, however, are important “amplification-hosts” for the spread of West Nile Virus, as the virus multiplies to exorbitant numbers within them. Some species can generate the highest levels of virus particles in their blood presently known for any viral infection; they can have millions of times more viral particles in their blood than similarly infected mammals. [2 for now]

Initial Infection

Birds may become infected with West Nile Virus in multiple ways. The most common occurrence is through a mosquito vector. However, studies have shown that they may contract the infection through ingestion of infected organisms or direct contact with infected materials.

Insect Vectors

Over 40 species of mosquitoes have been found to carry West Nile Virus. The most important for spread is the genus Culex, which mainly feed on birds. If a mosquito feeds off an infected host with high enough viral load (approximately one million virus particles per milliliter of blood), it will take up the virus into its gut. The virus will then multiply and spread to the rest of the mosquito’s body, including its salivary glands. The vector may then feed off another animal and transmit the virus to a new host.

Other blood sucking insects, such as ticks, have been found to be able to transmit the virus, though they are not as important for spread[2 again].

Oral Transmission

Birds may become infected by West Nile Virus through consuming infected prey items such as insects, small mammals, and other birds. After ingesting infected organisms, viremia usually occurs identically to that of mosquito-borne transmission [xx].

Contact Transmission

Contact Transmission: Research has found that it is possible for birds to transmit the virus to one another as a result of emitting particles in oral or cloacal secretions. These secretions may contaminate water and food, or may directly contact another susceptible organism. In captivity this process is rare, and it is unknown how common it occurs in nature. It is hypothesized that this contact transmission route a factor in spread of the virus in communal populations and during breeding seasons. [1I think]

Species Susceptibilities and Competence

| Table of West Nile Virus host competency of 24 species of birds [1x for now]. | |

| Species | Reservoir Competence Index |

|---|---|

| Blue Jay | 2.55 |

| Common Grackle | 2.04 |

| House Finch | 1.76 |

| American Crow | 1.62 |

| House Sparrow | 1.59 |

| Ring-billed Gull | 1.26 |

| Black-billed Magpie | 1.08 |

| American Robin | 1.08 |

| Red-winged Blackbird | 0.99 |

| American Kestrel | 0.93 |

| Great Horned Owl | 0.88 |

| Killdeer | 0.87 |

| Fish Crow | 0.73 |

| Mallard | 0.48 |

| European Starling | 0.22 |

| Mourning Dove | 0.19 |

| Northern Flicker | 0.06 |

| Canada Goose | 0.03 |

| Rock Dove | 0 |

| American Coot | 0 |

| Japanese Quail | 0 |

| Ring-necked Pheasant | 0 |

| Monk Parakeet | 0 |

Over 300 species of birds have been found infected with West Nile Virus. Passerine birds (of the order Passeriformes, such as flycatchers, robins, wrens, mockingbirds, and finches), charadiiform birds (of the order Charadriiformes, such as gulls, plovers, and stilts), and many raptors have been found to be competent hosts for viral infection and spread. In particular, Corvids (species of the family Corviade, including crows, ravens, magpies, and jays), as well as a few other sensitive species, such as American Kestrels and Great Horned Owls, are competent and highly susceptible. Birds of the orders Anseriformes (ducks, geese), Columbiformes (pigeons), Galliformes (chickens, turkeys), Gruiformes (rails, coots), Piciformes (woodpeckers, toucans), and Psittaciformes (parrots) are generally less competent.

The table to the left shows analyzed viremia data from mosquito-exposed birds. Data was compiled on these species and used to calculate each of their "competence index" numbers. Species with higher reservoir competence have higher concentrations of infection virus particles in their blood in combination with a long duration of an infectious level of viremia. Thus, they are better “amplifying hosts” for the disease, and are more likely to spread the disease. [1x]

Occurrence of mortality due to infection increases with species competence. In early studies of WNV in the United States, up to 100% mortality was observed in American Crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) and Blue Jays (Cyanocitta cristata) experimentally inoculated with the virus. It is suspected that WNV infection may require underlying illnesses or immune suppression in particular species to result in death. [1x]

It has been found that some species, such as American Crows, may contain a high enough viremia level that they are still able to transmit viral particles post-mortem to vector hosts that feed on their remains. [2]

Infection Symptoms

The majority of individual birds infected with West Nile Virus do not get sick or show symptoms. However, if they do become sick, clinical signs may include uncoordinated walking, lethargy, ataxia, weakness, tremors, inability to fly, anorexia followed by rapid weight loss, green waste products, blindness, lack of awareness, head droop, and abnormal body posture. They usually die within 24 to 48 hours of showing symptoms. In the final phase of infection preceding death, there birds may have severe tremors or seizures. These symptoms reflect virus infection and inflammation of the brain and spinal cord, as well as damage to other tissues, such as the heart, lungs, liver, etc. [xi, xii]

Through bird necropsies, organs found to be most frequently infected with virus particles are the spleen, kidney, skin, and eye. Usually, the virus first appears in the spleen, then rapidly spreads to other organs, and reaches the central nervous system later. Tissue distribution occurs earlier in more susceptible of the bird species. Histologic lesions, such as mild to severe encephalitis, necrosis, inflammation, and hemorrhages, have been found in multiple tissues, including the brain, spinal cord, eye, peripheral nervous system, heart, spleen, liver, kidney, lung, gastrointestinal tract, endocrine system, gonads, skeletal muscle, skin, and bone marrow. The speed of viral distribution and host death may affect the development of lesions, as hosts with higher susceptibility may die before lesions become observable. Macroscopic changes due to infection include emaciation, dehydration, multi-organ hemorrhages, and congestion. [xixix, xiii]

Host Factors

There is little evidence about why bird species are affected by West Nile Viruses differently. Some speculation and study points to life-style differences, such as breeding systems and geographic spread. Other differences may arise from immune-response capabilities and genetics.

Geography

Phylogenetically related, geographically divergent species have been shown to be differently affected by West Nile Virus infection. Thus, their geographic spread is thought to influence their susceptibility. More southern-living species may acquire cross-reactive immunologic protection because they are more frequently exposed to mosquito born Flaviviridae infections. [xiiii]

Breeding Systems

Immunity/Genetics

Chickens!

Virus Effect on Bird Populations

Eagles! Endandered?? Crows decline come back. Allows other species to spread?

Further Reading

[Sample link] Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Special Pathogens Branch

References

1x. Komar, N., S. Langevin, S. Hinten, N. Nemeth, E. Edwards, D. Hettler, B. Davis, R. Bowen, and M. Bunning. 2003. Experimental Infection of North American Birds with the New York 1999 Strain of West Nile Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 9(3): 311-322.

2. Greene, S. E., and A. Reid. (2013). FAQ: West Nile Virus, July 2013. American Society For Microbiology.

Xii "West Nile Virus." Seattle Audubon Society. Web. 9 Mar. 2014. <http://www.seattleaudubon.org/sas/LearnAboutBirds/SeasonalFacts/WestNileVirus.aspx>.

Xi "Frequently Asked Questions about West Nile Virus and Wildlife." USGS National Wildlife Health Center. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Mar. 2014. <http://www.nwhc.usgs.gov/disease_information/west_nile_virus/frequently_asked_questions.jsp>.

Xiii Gamino, Virginia, and Ursula Höfle. "Pathology and tissue tropism of natural West Nile virus infection in birds: a review." Veterinary Research 44.1 (2013): 39. Print

Xixixi Nemeth, Nicole, Daniel Gould, Richard Bowen, and Nicholas Komar. "Natural And Experimental West Nile Virus Infection In Five Raptor Species." Journal of Wildlife Diseases 42.1 (2006): 1-13. Print.

xxi. Taylar, Ingrid. Crows. 2012. Seattle, WA. flickr. Web. 9 Mar. 2014. <http://www.flickr.com/photos/taylar/8516674909/>.

xx: Nemeth, Nicole, Daniel Gould, Richard Bowen, and Nicholas Komar. "Natural And Experimental West Nile Virus Infection In Five Raptor Species." Journal of Wildlife Diseases 42.1 (2006): 1-13.

Edited by Leah Pomerantz, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.