West Nile Virus in Birds

West Nile Virus, of the family Flaviviridae, is a zoonotic disease that infects many species, including humans, throughout the world. Birds are the virus’s primary natural reservoir, where they act as the amplifier host. but their host competency (their ability to perpetuate the virus' development and spread) and response to infection varies between species; they can have diverging viral loads, viremia, viral shedding, clinical signs, and morbidity. Many factors may affect a particular organism and/or species’ susceptibility and response to infection, based on their life histories, immune-response capabilities, previous immunities, breeding systems, genetics, and stress levels. Birds vary widely in how they are affected by West Nile Virus.

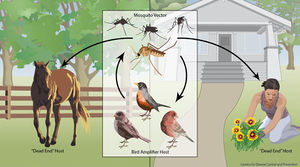

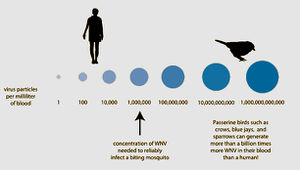

Most mammals, including horses and humans, are “dead-end” hosts for West Nile Virus, as, after infection, the virus does not become in high enough concentration in the blood to then be spread to insect vectors. Many bird species, however, are important “amplification-hosts” for the spread of West Nile Virus, as the virus multiplies to exorbitant numbers within them. Some species can generate the highest levels of virus particles in their blood presently known for any viral infection; they can have millions of times more viral particles in their blood than similarly infected mammals. [2 for now]

Initial Infection

Birds may become infected with West Nile Virus in multiple ways. The most common occurrence is through a mosquito vector. However, studies have shown that they may contract the infection through ingestion of infected organisms or direct contact with infected materials.

Insect Vectors

Over 40 species of mosquitos have been found to carry West Nile Virus. The most important for spread is the genus Culex, which mainly feed on birds. If a mosquito feeds off an infected host with high enough viral load (approximately one million virus particles per milliliter of blood), it will take up the virus into its gut. The virus will then multiply and spread to the rest of the mosquito’s body, including its salivary glands. The vector may then feed off another animal and transmit the virus to a new host.

Other blood sucking insects, such as ticks, have been found to be able to transmit the virus, though they are not as important for spread.

Oral Transmission

By ingesting infected mice or other birds, a carnivorous bird may present viremia.

Contact Transmission

Studies have shown transmission of infection between animals feces.

Species Susceptibilities and Competence

Corvids and stuff. lots of virus. competent for spread. boom.

The table is under me.

| Table 1. West Nile Virus Host Competency of 25 Species of Birds [1 for now]. | |

| Species | Reservoir Competence Index* |

|---|---|

| Blue Jay | 2.55 |

| Common Grackle | 2.04 |

| House Finch | 1.76 |

| American Crow | 1.62 |

| House Sparrow | 1.59 |

| Ring-billed Gull | 1.26 |

| Black-billed Magpie | 1.08 |

| American Robin | 1.08 |

| Red-winged Blackbird | 0.99 |

| American Kestrel | 0.93 |

| Great Horned Owl | 0.88 |

| Killdeer | 0.87 |

| Fish Crow | 0.73 |

| Mallard | 0.48 |

| European Starling | 0.22 |

| Mourning Dove | 0.19 |

| Northern Flicker | 0.06 |

| Canada Goose | 0.03 |

| Rock Dove | 0 |

| American Coot | 0 |

| Japanese Quail | 0 |

| Northern Bobwhite | 0 |

| Ring-necked Pheasant | 0 |

| Monk Parakeet | 0 |

| *based on susceptibility, mean infectiousness and duration (days) | |

Birds.

birds yep.

wow such a large table I wish I knew how to collapse it

Infection Responses and Symptoms

Lots of things.

Host Factors for Susceptibility and Competence

Geography

Life Style

Immunity/Genetics

Chickens!

Effect on bird populations

Eagles! Endandered?? Crows decline come back. Allows other species to spread?

Further Reading

[Sample link] Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Special Pathogens Branch

References

1. Komar, N., S. Langevin, S. Hinten, N. Nemeth, E. Edwards, D. Hettler, B. Davis, R. Bowen, and M. Bunning. 2003. Experimental Infection of North American Birds with the New York 1999 Strain of West Nile Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 9(3): 311-322.

2. Greene, S. E., and A. Reid. (2013). FAQ: West Nile Virus, July 2013. American Society For Microbiology.

Edited by Leah Pomerantz, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.