Zoonosis: Brucellosis in Animals and Humans: Difference between revisions

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

<br>By Hannah Wedig<br><br> | <br>By Hannah Wedig<br><br> | ||

Brucellosis is among the most common and highly contagious zoonoses. Zoonoses are diseases which can be transmitted from animals to humans. <ref name = “Seleem”>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113509003058. Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 140:392–398.]</ref> In the case of brucellosis, mammals – domestic, wild, terrestrial, and marine – are capable of transmitting the disease. <ref name = “Seleem”>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113509003058. Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 140:392–398.]</ref> <ref name = "Taleski">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037811350200250X. Taleski, V., Zerva, L., Kantardijev, T., Cvetnic, Z., Erski-Biljic, M. et al. 2002. An overview of the epidemiology and epizootiology of brucellosis in selected countries of Central and Southeast Europe. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 90:147–155.]</ref> Brucellosis is caused by certain species of bacteria in the genus <i>Brucella</i>, the most common and virulent of which are <i>B. melitensis, B. suis,</i> and <i>B. abortus</i> (Figure 1). <ref name = "Hagan">Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. <i>Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility</i>. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.</ref> <ref name = "Young">[http://www.antimicrobe.org/new/b87.asp. Young, E. J., M.D. “Brucella species (Brucellosis).” Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. Antimicrobe, 2014 Web.]</ref> The genus <i>Brucella</i> is within the class <i>α-Proteobacteria</i>, which includes many bacterial parasites of both plants and animals. <ref name = "Moreno and Moriyon">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC117501/. Moreno, E. and Moriyon, I. 2002. <i>Brucella melitensis</i>: A nasty bug with hidden credentials for virulence. <i>Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA.</i> 99:1–3.]</ref> <br><br>All <i>Brucella</i> are miniscule (≈ 0.5µm-1.5µm in diameter), sessile, Gram-negative coccobacilli, and are facultative intracellular pathogens (Figure 2). <ref name = "Godfroid">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23837363. Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. 2013. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. <i>Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz.</i>, 32:27–42.]</ref> <ref name = "Hagan">Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. <i>Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility</i>. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.</ref> When cultured, <i>Brucella</i> colonies appear either smooth or rough. Smooth colonies are more common in the virulent species of <i>Brucella</i> (e.g. <i>B. melitensis, suis</i>, and <i>abortus</i>), and rough colonies are associated with non-virulent species. The rough morphotype is attributed to a lipopolysaccharide molecule that elicits strong immune responses in animals, which may explain why it is associated with the non-virulent species. <ref name = "Schurig">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113502002559. Schurig, G. G., Sriranganathan, N., Corbel, M. J. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i>, 90:479–496.]</ref> <br><br><i>Brucella</i> are capable of surviving, but rarely reproduce, in external environments for well over a year given the appropriate conditions. <ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” <i>Brucella melitensis</i> (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> They fare best in environments with a pH greater than 5.5, high humidity, and, most especially, freezing temperatures <ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> <ref name = "BA">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_abortus.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella abortus.” <i>Brucella abortus</i> (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> In animals, Brucella can be found all over the globe, with notably high occurrences in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Latin America, and Africa.<ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> The highest incidences of Brucella in humans are recorded in Syria and Mongolia (Figure 3) <ref name = "Ariza">[http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040317#pmed-0040317-g001. Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D., Corbel, M. J., Falagas, M. E., <i>et al.</i> 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations. <i>PLoS Med</i> 4(12):317.]</ref> <br><br>The first concrete documentation of brucellosis symptoms in humans occurred in the 1850’s when a British Army surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Marston, described a fever he had, the symptoms of which differed from any other known fever at the time <ref | Brucellosis is among the most common and highly contagious zoonoses. Zoonoses are diseases which can be transmitted from animals to humans. <ref name = “Seleem”>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113509003058. Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 140:392–398.]</ref> In the case of brucellosis, mammals – domestic, wild, terrestrial, and marine – are capable of transmitting the disease. <ref name = “Seleem”>[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113509003058. Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 140:392–398.]</ref> <ref name = "Taleski">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037811350200250X. Taleski, V., Zerva, L., Kantardijev, T., Cvetnic, Z., Erski-Biljic, M. et al. 2002. An overview of the epidemiology and epizootiology of brucellosis in selected countries of Central and Southeast Europe. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i> 90:147–155.]</ref> Brucellosis is caused by certain species of bacteria in the genus <i>Brucella</i>, the most common and virulent of which are <i>B. melitensis, B. suis,</i> and <i>B. abortus</i> (Figure 1). <ref name = "Hagan">Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. <i>Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility</i>. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.</ref> <ref name = "Young">[http://www.antimicrobe.org/new/b87.asp. Young, E. J., M.D. “Brucella species (Brucellosis).” Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. Antimicrobe, 2014 Web.]</ref> The genus <i>Brucella</i> is within the class <i>α-Proteobacteria</i>, which includes many bacterial parasites of both plants and animals. <ref name = "Moreno and Moriyon">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC117501/. Moreno, E. and Moriyon, I. 2002. <i>Brucella melitensis</i>: A nasty bug with hidden credentials for virulence. <i>Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA.</i> 99:1–3.]</ref> <br><br>All <i>Brucella</i> are miniscule (≈ 0.5µm-1.5µm in diameter), sessile, Gram-negative coccobacilli, and are facultative intracellular pathogens (Figure 2). <ref name = "Godfroid">[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23837363. Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. 2013. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. <i>Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz.</i>, 32:27–42.]</ref> <ref name = "Hagan">Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. <i>Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility</i>. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.</ref> When cultured, <i>Brucella</i> colonies appear either smooth or rough. Smooth colonies are more common in the virulent species of <i>Brucella</i> (e.g. <i>B. melitensis, suis</i>, and <i>abortus</i>), and rough colonies are associated with non-virulent species. The rough morphotype is attributed to a lipopolysaccharide molecule that elicits strong immune responses in animals, which may explain why it is associated with the non-virulent species. <ref name = "Schurig">[http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378113502002559. Schurig, G. G., Sriranganathan, N., Corbel, M. J. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. <i>Veterinary Microbiology</i>, 90:479–496.]</ref> <br><br><i>Brucella</i> are capable of surviving, but rarely reproduce, in external environments for well over a year given the appropriate conditions. <ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” <i>Brucella melitensis</i> (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> They fare best in environments with a pH greater than 5.5, high humidity, and, most especially, freezing temperatures <ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> <ref name = "BA">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_abortus.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella abortus.” <i>Brucella abortus</i> (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> In animals, Brucella can be found all over the globe, with notably high occurrences in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Latin America, and Africa.<ref name = "BM">[http://wildpro.twycrosszoo.org/S/0zM_Gracilicutes/Brucella/Brucella_melitensis.htm. Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.]</ref> The highest incidences of Brucella in humans are recorded in Syria and Mongolia (Figure 3) <ref name = "Ariza">[http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.0040317#pmed-0040317-g001. Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D., Corbel, M. J., Falagas, M. E., <i>et al.</i> 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations. <i>PLoS Med</i> 4(12):317.]</ref> <br><br>The first concrete documentation of brucellosis symptoms in humans occurred in the 1850’s when a British Army surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Marston, described a fever he had, the symptoms of which differed from any other known fever at the time <ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4026726/. Moreno, E. 2014. Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. <i>Front Microbiol.</i>, 5:1–18.]</ref> <ref>[https://www.oie.int/doc/ged/D12396.PDF. Wyatt, H. V. 2013. Lessons from the history of brucellosis. <i>Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz.</i>, 32:17–25.]</ref> | ||

Revision as of 20:27, 27 April 2017

Introduction

By Hannah Wedig

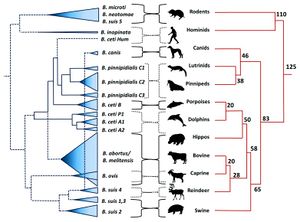

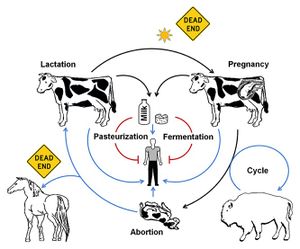

Brucellosis is among the most common and highly contagious zoonoses. Zoonoses are diseases which can be transmitted from animals to humans. [1] In the case of brucellosis, mammals – domestic, wild, terrestrial, and marine – are capable of transmitting the disease. [1] [2] Brucellosis is caused by certain species of bacteria in the genus Brucella, the most common and virulent of which are B. melitensis, B. suis, and B. abortus (Figure 1). [3] [4] The genus Brucella is within the class α-Proteobacteria, which includes many bacterial parasites of both plants and animals. [5]

All Brucella are miniscule (≈ 0.5µm-1.5µm in diameter), sessile, Gram-negative coccobacilli, and are facultative intracellular pathogens (Figure 2). [6] [3] When cultured, Brucella colonies appear either smooth or rough. Smooth colonies are more common in the virulent species of Brucella (e.g. B. melitensis, suis, and abortus), and rough colonies are associated with non-virulent species. The rough morphotype is attributed to a lipopolysaccharide molecule that elicits strong immune responses in animals, which may explain why it is associated with the non-virulent species. [7]

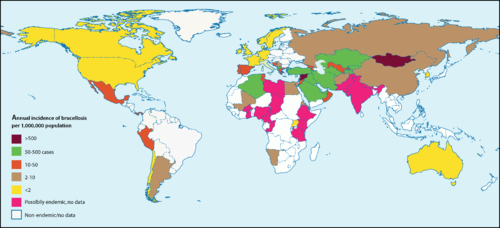

Brucella are capable of surviving, but rarely reproduce, in external environments for well over a year given the appropriate conditions. [8] They fare best in environments with a pH greater than 5.5, high humidity, and, most especially, freezing temperatures [8] [9] In animals, Brucella can be found all over the globe, with notably high occurrences in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Latin America, and Africa.[8] The highest incidences of Brucella in humans are recorded in Syria and Mongolia (Figure 3) [10]

The first concrete documentation of brucellosis symptoms in humans occurred in the 1850’s when a British Army surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Marston, described a fever he had, the symptoms of which differed from any other known fever at the time [11] [12]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [19]

[20]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Section 1

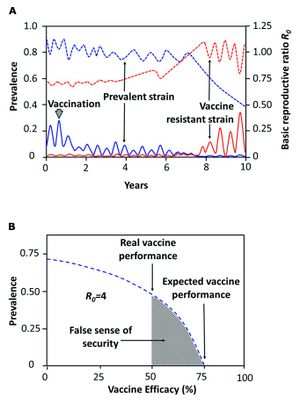

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above.

Section 2

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. Veterinary Microbiology 140:392–398.

- ↑ Taleski, V., Zerva, L., Kantardijev, T., Cvetnic, Z., Erski-Biljic, M. et al. 2002. An overview of the epidemiology and epizootiology of brucellosis in selected countries of Central and Southeast Europe. Veterinary Microbiology 90:147–155.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.

- ↑ Young, E. J., M.D. “Brucella species (Brucellosis).” Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. Antimicrobe, 2014 Web.

- ↑ Moreno, E. and Moriyon, I. 2002. Brucella melitensis: A nasty bug with hidden credentials for virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:1–3.

- ↑ Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. 2013. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 32:27–42.

- ↑ Schurig, G. G., Sriranganathan, N., Corbel, M. J. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. Veterinary Microbiology, 90:479–496.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Bourne, D. “Brucella abortus.” Brucella abortus (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.

- ↑ Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D., Corbel, M. J., Falagas, M. E., et al. 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations. PLoS Med 4(12):317.

- ↑ Moreno, E. 2014. Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. Front Microbiol., 5:1–18.

- ↑ Wyatt, H. V. 2013. Lessons from the history of brucellosis. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 32:17–25.

- ↑ Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. 2014. Moreno, E. Front Microbiol. 5: 213.

- ↑ "Brucella Melitensis." Database of Bacterial Food Pathogen. Birla Institute of Scientific Research, 2015.

- ↑ Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. 2013. Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 32 (1): 27-42

- ↑ Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D. et al. "Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations." 2008. PLoS Med 4(12): e317

- ↑ Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. 2014. Moreno, E. Front Microbiol. 5: 213.

- ↑ Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. 2014. Moreno, E. Front Microbiol. 5: 213.

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.