Zoonosis: Brucellosis in Animals and Humans

Introduction

By Hannah Wedig

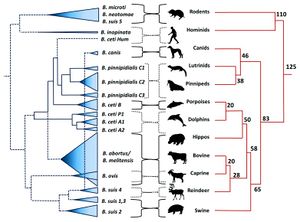

Brucellosis is among the most common and highly contagious zoonoses. Zoonoses are diseases which can be transmitted from animals to humans. [1] In the case of brucellosis, mammals – domestic, wild, terrestrial, and marine – are capable of transmitting the disease. [1] [2] Brucellosis is caused by certain species of bacteria in the genus Brucella, the most common and virulent of which are B. melitensis, B. suis, and B. abortus (Figure 1). [3] [4] The genus Brucella is within the class α-Proteobacteria, which includes many bacterial parasites of both plants and animals. [5]

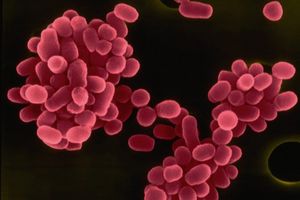

All Brucella are miniscule (≈ 0.5µm-1.5µm in diameter), sessile, Gram-negative coccobacilli, and are facultative intracellular pathogens (Figure 2). [7] [3] When cultured, Brucella colonies appear either smooth or rough. Smooth colonies are more common in the virulent species of Brucella (e.g. B. melitensis, suis, and abortus), and rough colonies are associated with non-virulent species. The rough morphotype is attributed to a lipopolysaccharide molecule that elicits strong immune responses in animals, which may explain why it is associated with the non-virulent species. [8]

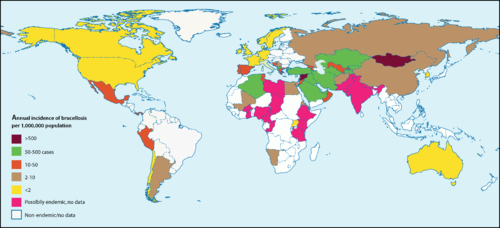

Brucella are capable of surviving, but rarely reproduce, in external environments for well over a year given the appropriate conditions. [11] They fare best in environments with a pH greater than 5.5, high humidity, and, most especially, freezing temperatures [11] [12] In animals, Brucella can be found all over the globe, with notably high occurrences in the Mediterranean, Middle East, Latin America, and Africa.[11] The highest incidences of Brucella in humans are recorded in Syria and Mongolia (Figure 3) [13]

The first concrete documentation of brucellosis symptoms in humans occurred in the 1850’s when a British Army surgeon, Dr. Jeffrey Marston, described a fever he had, the symptoms of which differed from any other known fever at the time. [6] [15] In 1887, the first species of Brucella (B. melitensis) was isolated from the spleens of Maltese soldiers who had come down with what was then called Malta fever (the earliest name for brucellosis). [6] [16] For a couple of decades, the transmission of this disease was a mystery, and people generally attributed it to “bad air” and poor public sanitation systems. A couple of decades later, a Maltese physician named Themistocles Zammit cleared the mystery by performing a series of ethically questionable experiments on goats. He fed his goats cultures of Brucella, observed their symptoms, and tested their urine, blood, and milk for presence of the bacteria. [15] Based on the results, he concluded that the disease’s causative agent was transmittable to humans through the ingestion of contaminated goat milk [17] A decade later, the abortive effects of Brucella in animals were discovered. [6]

Transmission, Signs, and Symptoms

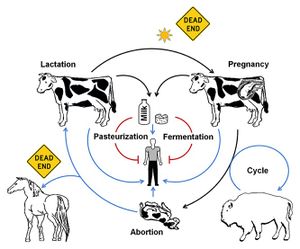

Themistocles Zammit had discovered the most common means of Brucella infection: ingestion of contaminated animal products (such as dairy products for humans, and aborted fetuses or placenta for animals). However, Brucella can also enter via the respiratory tract, broken skin, or any mucous membranes that come into contact with infected fluids or tissues (such as feces, urine, milk, fetal fluids, vaginal discharge, semen, placenta, aborted fetuses, etc.). [11]

In humans, Brucella primarily inhabit parts of the phagocytic system including lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow. The incubation period can range from one to three weeks, during which the cells remain in the phagocytic system and replicate.[6] Because of this, symptoms may be entirely absent up to several months after infection. The symptoms, once they arise, have been described as so bad “‘it often makes a patient wish he were dead”.[1] Human brucellosis caused by B. melitensis was first known as Malta fever (though it has an abundance of other names, such as Mediterranean fever, Corps disease, undulant fever, Cyprus fever, to name a few), an illness characterized by fatigue and back pain in addition to elevated body temperatures.[11] [6] Other species of Brucella can cause a range of complications including anorexia, myalgia, encephalitis, meningitis, endocarditis, and various forms of arthritis [18] [1] Although rarely fatal, if left untreated, brucellosis can become a chronic, debilitating disease. [19] It is also not uncommon for infected individuals to have a relapse as early as several months after recovering from the initial infection. [20]

In animals, Brucella can inhabit an array of organs, including the aforementioned ones in phagocytic system but also the kidneys and reproductive organs. If a pregnant female is infected, the bacteria can cause premature birth or spontaneous abortion of the fetus – this can also occur in female humans, but is much less common.[21] Most infected female animals will only abort once but, if untreated, their placenta can retain the bacteria and cause complications in subsequent birthings.[1]

Brucella have also been isolated from a range of arthropods including ticks, bedbugs, lice, and mites. Though these paratenic hosts do not support Brucella reproduction, they can function as brucellosis vectors.[11]

As previously mentioned, Brucella fare best in cooler conditions and are extremely susceptible to heat – a mere hour or two of exposure to direct sunlight will kill the bacteria.[6] [12] In addition to sunlight exposure, mammals that are resistant to the bacteria and or mammals (such as humans) that rarely pass on the bacteria are considered “dead ends” in terms of bacterial transmission (Figure 4).[6]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: PHIL_1181_lores.jpg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [22]

[23]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Major Brucella Species

Terrestrial

B. melitensis

Among the ten known species of Brucella, B. melitensis is the most common and most pathogenic for humans. [1] [7] [16] Sheep and goats are the predominant natural hosts of B. melitensis, but it has been isolated from a vast array of other mammals including humans, cattle, deer, squirrels, guinea pigs, mice, hedgehogs, fox, dogs, cats, chickens, and frogs.[11] [24] B. melitensis is aerobic, and does not require supplementary CO2 to grow (see B. abortus).[11]

B. suis

B. suis is most commonly found in domestic pigs and wild boars, but can also inhabit humans, peccary, cattle, moose, horses, bears, fox, voles, ravens, and turkeys. Like B. melitensis, B. suis is aerobic and does not rely on increased levels of CO2 for growth. [25] Unlike B. melitensis, certain subspecies of B. suis produce H2S during growth. The pathogenicity of B. suis is variable, but is typically less virulent than B. melitensis and more virulent than B. abortus.[25] [26]

B. abortus

B. abortus typically infects cattle, bison, yaks, buffalo, and sheep, but has also been discovered in humans, deer, horses, coyotes, fox, badgers, raccoons, and opossums.

Section 2

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Seleem, M. N., Boyle, S. M., Sriranganathan, N. 2010. Brucellosis: A re-emerging zoonosis. Veterinary Microbiology 140:392–398.

- ↑ Taleski, V., Zerva, L., Kantardijev, T., Cvetnic, Z., Erski-Biljic, M. et al. 2002. An overview of the epidemiology and epizootiology of brucellosis in selected countries of Central and Southeast Europe. Veterinary Microbiology 90:147–155.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hagan, W. A., Bruner, W. D. Hagan and Bruner’s Microbiology and Infectious Diseases of Domestic Animals: With Reference to Etiology, Epizootiology, Pathogenesis, Immunity, Diagnosis, and Antimicrobial Susceptibility. Ithaca: Comstock Publ., 1992. Print.

- ↑ Young, E. J., M.D. “Brucella species (Brucellosis).” Infectious Disease and Antimicrobial Agents. Antimicrobe, 2014 Web.

- ↑ Moreno, E. and Moriyon, I. 2002. Brucella melitensis: A nasty bug with hidden credentials for virulence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:1–3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Moreno, E. 2014. Retrospective and prospective perspectives on zoonotic brucellosis. Front Microbiol., 5:1–18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. 2013. Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 32:27–42.

- ↑ Schurig, G. G., Sriranganathan, N., Corbel, M. J. 2002. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future. Veterinary Microbiology, 90:479–496.

- ↑ "Brucella Melitensis." Database of Bacterial Food Pathogen. Birla Institute of Scientific Research, 2015.

- ↑ Brucellosis in terrestrial wildlife. 2013. Godfroid, J., Garin-Bastuji, B., Saegerman, C., Blasco, J. M. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz. 32 (1): 27-42

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7

Bourne, D. “Brucella melitensis.” Brucella melitensis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content Cite error: Invalid<ref>tag; name "BM" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 12.0 12.1 Bourne, D. “Brucella abortus.” Brucella abortus (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n.d. Web.

- ↑ Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D., Corbel, M. J., Falagas, M. E., et al. 2007. Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations. PLoS Med 4(12):317.

- ↑ Ariza, J., Bosilkovski, M., Cascio, A., Colmenero, J. D. et al. "Perspectives for the Treatment of Brucellosis in the 21st Century: The Ioannina Recommendations." 2008. PLoS Med 4(12): e317

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wyatt, H. V. 2013. Lessons from the history of brucellosis. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 32:17–25.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Nicoletti, P. 2002. A short history of brucellosis. Veterinary Microbiology 90:5–9.

- ↑ Wyatt, H. V. 2005. How Themistocles Zammit found Malta Fever (brucellosis) to be transmitted by the milk of goats. J. R. Soc. Med. 98:451–454.

- ↑ Wong, K. “Brucella melitensis.” MicrobeWiki. Kenyon College. 7 July 2011. Web.

- ↑ Corbel, M. J. Brucellosis in Humans and Animals. World Health Organization. 2006. Print.

- ↑ Al Dahouk, S., Sprague, L. D., Neubauer, H. 2013 New developments in the diagnostic procedures for zoonotic brucellosis in humans. Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 32:177–188.

- ↑ Corbel, M. J. Brucellosis in Humans and Animals. World Health Organization. 2006. Print.

- ↑ Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

- ↑ Bartlett et al.: Oncolytic viruses as therapeutic cancer vaccines. Molecular Cancer 2013 12:103.

- ↑ “Zoonoses.” Health Concerns to be Aware of When Working With Wildlife. Wildlife Rehab Info. n.d. Web.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bourne, D. “Brucella suis.” Brucella suis (Bacterial Type). Twycross Zoo, n. d. Web.

- ↑ Galinska, E. M., Zagorski, J. 2013 Brucellosis in humans – etiology, diagnostics, clinical forms. Annals of Agri. Env. Med. 20:233–238.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.