Anthrax

History

Anthrax has been described since antiquity. Stories of anthrax plague appear in the Bible and the ancient Greeks described the cutaneous infection as coal-like (anthrakites) in appearance. The Roman poet Virgil also discussed the disease in domestic animals. Anthrax continued to affect domestic animals and humans in the Middle Ages and was referred as "woolsorters' disease" in England due to mill workers contracting the disease from sheep wool. Anthrax cases in the 20th century decreased significantly due to vaccination of animals. [13]

The discovery of Bacillus anthracis is credited to Pollender, Rayer and Davaine. Robert Koch proved that the anthrax bacillus caused the disease. Koch did this by removing anthrax bacilli from the spleens of mice that had died from the disease and injected the blood into healthy mice, which killed the previously healthy mice. This illustrated the disease could be passed by blood from infected animals. He also created pure cultures of the bacilli and showed that this also caused disease. [12]These experiments served as the prototype for Koch's postulates.[13]

Etiology/Bacteriology

Taxonomy

Domain: Bacteria

Phylum: Firmicutes

Class: Bacilli

Order: Bacillales

Family: Bacillaceae

Genus: Bacillus

Species: anthracis

Description

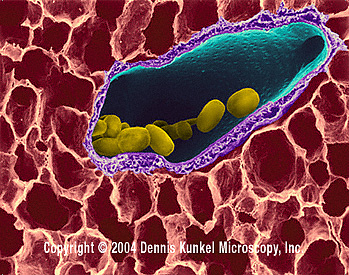

Bacillus anthracis is a Gram-positive facultative aerobic, spore-forming bacterium found in the soil. B. anthracis derived its name from the Greek word for coal because this pathogen causes black lesions on the victim's skin. The bacterium is non-motile and non-hemolytic on blood agar. B. anthracis is found mostly in spore-form in the environment, but when it has infected a host it will germinate and replicate in essentially all body tissues.[3] When anthracis is in the spore form, it is resistant to most adverse environments and can survive for many decades. [2]

Pathogenesis

B. anthracis pathogenesis begins by the spores entering a skin abrasion, lungs, or intestines. There, the spores are ingested by macrophages and brought to lymph nodes. The bacteria germinate in the lymph nodes or mediastinum, in the case of inhalation anthrax. Local production of toxins cause edema and necrosis then bacterimia and toxemia. Seeding of other organ systems occur and the infection spreads. [5]

Transmission

The most common way a human can contract anthrax is being in contact with infected animal products.[4] Herbivore grazing animals can commonly contract anthrax because anthracis lives in the soil. A person may get anthrax by inhaling the spores from animal products, such as wool, have an open abrasion on the skin be exposed to the spores, or eating undercooked meat from an animal that was infected. More than 90% of anthrax cases are cutaneous exposures. Anthrax cannot be spread person-to-person. [2]

Infectious dose, incubation, and colonization

The infectious dose of B. anthracis is not entirely clear. Some suggest 100 spores will cause infection while other analyses have shown as few as 1-3 spores can cause infection. For inhalation anthrax, the infectious dose can be 8-50,000 spores.

The incubation time also depends on what type of anthrax is contracted. For inhalation anthrax, the incubation period is 2-5 days. Cutaneous anthrax will start to manifest symptoms within 2-3 days, with some cases being as short as 12 hours. Gastrointestinal anthrax is much more rare and the incubation time isn't known.

If infected with inhalation anthrax, the spores are deposited in the alveolar spaces and then transported to mediastinal lymph nodes. After the spores germinate the vegetative bacteria will spread to the blood and lymph and cause septecimia. For ingested and cutaneous anthrax, the spores enter through a break in the skin or a break in the mucosa of the intestines. They are engulfed by macrophages, where they germinate and then extracellular replication will occur. During this replication phase, the capsule and toxin begin to be secreted which will cause symptoms and the disease. [2]

Epidemiology

Most inhalation anthrax cases have occured in the factory setting when workers are exposed to contaminated animal products, like wool. Inhalation anthrax is very rare in the United States due to vast vaccination of domesticated livestock. Gastrointestinal anthrax is the rarest form of anthrax, and in the United States there has only been two reported cases. In 2010, the Philippines had a 400 person outbreak of gastrointestinal anthrax from eating meat from a dead infected caribou. The largest epidemic to date happened in Zimbabwae between 1979-1985 when 10,000 people contracted cutaneous anthrax. [2]

Virulence factors

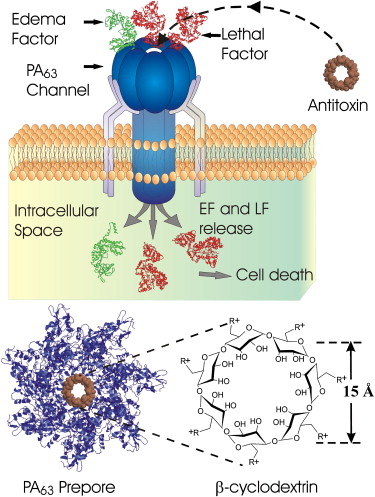

Bacillus anthracis has two components to its virulence. The toxin it secrets as well as its capsule. The capsule is composed of D-glutamyl polypeptide. Plasmid pXO2 is involved in the formation of the capsule. The capsule prevents host phagocytosis when B. anthracis is in its vegetative form. Plasmid pXO1 is responsible for the toxin released. The toxin has three proteins: the edema factor, lethal factor, and protective antigen. The protective antigen is a binding domain that allows the toxins (edema and lethal factors) to enter host cells. Lethal toxin causes immunosuppressive effects as well as damage endothelial cell function and causes cell apoptosis. Lethal factor also disrupts downstream signaling, which is important in normal cell functioning. Edema factor is a potent adenyl cyclase and works additively with lethal factor. EF causes increase cAMP production in infected cells and also has immunosuppressive effects like LF. Both plasmids for capsule formation and toxin secretion have to be present in order for B. anthracis to be virulent. [2] [7] [8]

Clinical features

Cutaneous

The first sign of a cutaneous anthrax infection is a papule that eventually forms an ulcer with a black center. These lesions are painless. Fever rarely occurs with cutaneous anthrax infections. [6]

Gastrointestinal

Gastrointenstinal anthrax presents itself initially with nausea, vomiting and anorexia, and fever. If left untreated, gastrointestinal anthrax will cause severe abdominal pain, haematemesis, bloody diarrhea, septicemia, and death. The initial symptoms our non-specific and can make it difficult to diagnose, resulting in a high mortality rate. [6]

Inhalation

If infected with inhalation anthrax, the first symptoms are flu-like and include fever, malaise, cough, and fatigue. After 48 hours, fever, tachypnoea, cyanosis, tachycardia, moist rales, and evidence of pleural effusion may be present. The pulse will be rapid and faint, the patient will become disoriented, and coma and death will soon follow. In half of the patients, meningitis will occur. Meningitis can occur from all three forms of anthrax and the mortality rate after contracting meningitis is near 100%.[6]

Diagnosis

To demonstrate that a patient is infected with B. anthracis, a methylene blue stain can be done as well as a blood agar culture. Anthrax will appear as a large Gram-positive rod after staining. A serologic diagnosis of anthrax can be made using a test specific for the protective antigen (PA) component of the toxin. [6]

Cutaneous

Cutaneous anthrax must first be distringuished from plague. The patient also has an appropriate history of being around exposed animals. A specimen may be obtained from the ulcer and cultured on sheep blood agar and then Gram-stained to demonstrate the organism.[6]

Gastrointestinal

To diagnose gastrointestinal anthax, it must be distinguished from dysentery. Obtaining a history of ingesting contaminated meat can be helpful. A stool sample negative for amebic cysts or trophs and for Shigella suggest the possibility of gastrointestinal anthrax.[6]

Inhalation

For a patient that has inhalation anthrax, hemorrhagic mediastinitis with bloody pleural effusions will be present as well as a widened mediastinum when observed under a CT scan.

[6]

Treatment

For a potential exposure to anthrax, a person should remove all contaminated clothing and wash with soap and water. Medical responders need to have appropriate protection from infection which includes gloves, splash protection, and a full-face respirator. If anthrax is confirmed, antibiotics should be administered. The CDC recommends ciprofloxacin and doxycycline. If anthrax meningitis is suspected, doxycycline shouldn't be used because it does not penetrate the central nervous system very well. Pregnant or breastfeeding women can use amoxicillin. For inhalation anthrax, it is recommended to use multi-drug therapy, such as vancomycin, with the chosen antibiotic. [6]

Prevention

Prevention methods for avoiding anthrax infection include: vaccinations, proper decontamination, and prophylactic treatments. Vaccinations exist for domestic animals and humans. Since anthrax is commonly acquired through contact with contaminated animal products, vaccination of animals is very important. Bovine anthrax vaccination is extremely effective, but usually has to be re-administered every year. Vaccination of humans is more common for bioterrorism cases, so American troops are vaccinated while it is uncommon for the general population to be vaccinated. If a human or animal has been suspected to die from anthrax, contact with the body should be avoided and the body and clothes should be burned. [4]

Host Immune Response

Lethal and Edema factors both have immunosuppressive effects that make anthrax such a lethal disease. LF and EF inhibit proliferation of CD4 T cells, neutrophile phagocytosis, cytokine production, IL-2 production, and cause macrophage lysis. Macrophages ingest the spores and carry them to regional lymph nodes. The Bacillus spores use these macrophages to bypass the immune response. Ingestion of the spores by the macrophages also induces chemokine and cytokine production which cause an inflammatory response. While neutrophils do play a role in the host immune response, alveolar macrophages (in the case of inhaled anthrax) play a more direct role with host defense of anthrax. Studies have shown that macrophages are critical to host survival during an anthrax infection. The immune system also produces anti-protective antigen (PA) immuglobulin G to combat the toxins secreted by B. anthracis by neutralizing lethal factor. PA-specific IgG memory B cells are also produced in infected persons and the levels of these memory cells are have been shown to be comparable or higher than those vaccinated. [8] [9] [10] [11]

Bioterrorism

Today, most people associate anthrax with biological warfare instead of a disease acquired from infected domesticated animals. A major effort during World War II sought to make anthrax a weapon. [2]During the fall of 2001, an anthrax outbreak occurred due to spore-containing mail. During this outbreak there were 11 confirmed cases of inhalation anthrax and 11 confirmed or suspected cases of cutaneous anthrax. Five people died. [13]

References

1. Conway, Tyrrell. “Genus conway”. “Microbe Wiki” 2013. Volume 1. p. 1-2.

2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1769905/

3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2784286/

4. http://www.bt.cdc.gov/agent/anthrax/needtoknow.asp

5. http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/diseases/anthrax/anslides.pdf

6. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/212127-clinical

7. http://iai.asm.org/content/49/2/291.full.pdf

8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2176088/

9. http://iai.asm.org/content/74/8/4430.full

10. http://iai.asm.org/content/74/1/469.full

11. http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/190/7/1228.full

12.http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1905/koch-bio.html

13. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12745053

Created by Danielle Vinnedge, student of Tyrrell Conway at the University of Oklahoma.