Cat Breed Evolution

Introduction

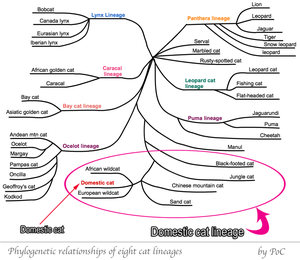

The evolution of domestic cat breeds is a long and interesting tale that started in 7500 BC in what was then called the Near East. These cats began their descent into the common domestic cat around 4400 BC when they began a mutually beneficial relationship with the earliest farmers.[1] In return for helping control rodent populations and providing company, these animals got food and protection from the elements. Different breeds began to appear when artificial selection led to the wide range in size, color, and behavior shown in modern day cats, whose Latin name is Felis catus.

There are many different ideas on how cats evolved to become domesticated like they are today. The most prevalent idea is that cats were able to board shipping line ships and travel around the world starting in 2000 BCE.[2] These cats stayed by the human’s side as feral pets, but were never fully controlled. They still hunted for their own food and bred how they wanted. This great migration of cats began in Western Asia and spread to Western Europe, the Mediterranean, and Africa.

Over time, around 1700 BCE, the demand for Egyptian cats increased 10 fold because of their beautiful fur and friendly dispositions. This led to a “cat trading ban” around 1500 BCE but by that time, cats had infiltrated most homes, hunting parties, and cities.[3]

Genetics

Genetic analysis has found that cats mostly domesticated themselves until around 100 BCE and there are striking similarities and differences between today’s house cat and past wild cats, as well as domesticated cats. As such, physical evolution is not the only type that occurred in these nine thousand years and researchers are now able to identify the genes that have changed. Since the beginning of their domestication, over 281[4] genes have mutated rapidly and sometimes multiple times. These genes are responsible for a cat’s hearing, metabolism, eye-sight, and even diet.

However, the most important genes that have shifted a wild cat to a domestic cat were found when comparing domestic cats to their ancestors who still roam Europe. These 13[5] genes are responsible for the cat’s cognition, identification of danger or prey, fear, and ability to recognize rewards and commands. In order to accomplish these tasks, the genes code for glutamate receptors, which are shown to be responsible for learning and memory in humans as well. These genes were present in the ancient cats who dared to board a ship with humans and have since evolved into a standard piece of DNA found in every house cat.

Another five genes that have been recently sequenced show that they affect the migration of stem cells in developing embryos which can explain common traits of domesticated animals such as smaller brains, lowered hunting ability, and different fur patterns.[6]

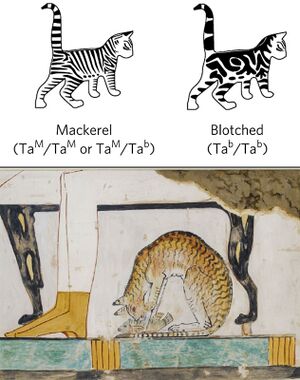

Fur is another trait that has genetically evolved to be where it is today. Long, “regal-looking” stripes of dark and tawny variations have been present since ancient times on wild cats and tabby cats. However, when tabby cats and calico cats started to develop splotches of fur instead of defined stripes, scientists identified one common factor: a mutated gene. This gene is called Taqpeq. This gene is responsible for the spacing and shape of the splotches but not the color. A different mutation has been found on the Edn3 gene that is shown to be responsible for black coloration not previously found in the wild. As Taqpeq levels are increased throughout the entire gestation period but fur patterns only appear in week 7, it is proposed that it is solely responsible for the establishment of a spotted or striped pattern with Edn3 coming later to establish color. This is why the number of spots or stripes on a house cat does not change throughout its entire lifespan.[7] Also, along with other factors such as ear hair, size of cat, nose shape, and more, these two genes are responsible for the differentiation of over 20 domesticated cat breeds.

Physical Evolution

Current research in the physical evolution of cats shows that the evolution of noises made by cats such as chattering and meowing has occurred within 500 years. This is in order to better communicate with humans; proven by the fact that most wild cats do not meow or chatter, they roar. Meowing allows domestic cats to express happiness, a need for something, and anger while chattering allows them to express frustration.

Also, further evolution of a cat’s physical appearance is from selective breeding. These cats are selected for certain physical traits such as ear size, tail size, length of fur, and fur colors. This breeding can be with two cats of similar traits or two different cats in order to create a desirable hybrid.[8]

Microbiome

There has been much research done in recent years on a domestic cat’s mouth, specifically the bacteria that resides inside of it. One main area of research is on the bacteria Pasteurella multocida. This bacteria is shown to be found in 70-90% of all domestic cat’s mouth’s and causes 50-80% of all staph infections and other skin issues after a bite.[9] Once bitten by a cat, it is recommended to go see a doctor even if it is not serious and to get on antibiotics if the swelling doesn’t go down after 24 hours. This is because humans do not have immunity to Pasteurella multocida unlike most other animals.

Another dangerous bacteria that is found in a cat’s mouth and on their claws is Bartonella henselae. This is commonly known as the “cat scratch disease” as that is how it is mainly transmitted. It causes similar symptoms to Pasteurella multocida which are swelling, redness, fever, and irritation.[10]

However, on the positive side, research stemming from an original experiment in the 1980’s shows that cats and humans can actually share their microbiomes, diversifying and enriching them in the process. This happens when humans have prolonged exposure to furry animals (usually cats) from a young age. These can be nasal, intestinal, and even skin microbiomes.[11]

Conclusion

Although the story of the evolution of domestic cats is incomplete on this page, the general idea is explained. There is still continuing dedication and research on this topic. Cats have been proven to be descended from the wildcats of the ancient age. However, when the domestic clade actually diverged from these wildcats is uncertain within a 1000 years. DNA shows the first domestic cats to be present around 2500 BC in Mesopotamia and Egypt and spread across Afro-Eurasia around 2000 BC. There is a possibility of multiple evolutions occurring simultaneously along with the migration.

The first domestic cats bared a remarkable resemblance to their wild counterparts but have since gained different features such as differently shaped claws, different fur colors, and different gut bacteria. This is partially due to natural evolution as well as selective breeding in hopes of creating purebreds as well as desirable hybrids. One thing is for certain, however. No matter the driving force, the evolution of domestic cats is far from over.

References

- ↑ Smith, Casey. “Cats Domesticated Themselves, Ancient DNA Shows.” Science. National Geographic, May 3, 2021.

- ↑ “How Did Cats Become Domesticated?” The Library of Congress. Accessed December 8, 2021.

- ↑ Annalee Newitz - Jun 19, 2017 8:01 pm UTC, and Aged Ars Veteran Wise. “Cats Are an Extreme Outlier among Domestic Animals.” Ars Technica, June 19, 2017.

- ↑ [ https://www.science.org/content/article/genes-turned-wildcats-kitty-cats. Schnoffer, Karli. “The Genes That Turned Wildcats into Kitty Cats | Science ...” Accessed December 8, 2021.]

- ↑ Montague, Michael J., Gang Li, Barbara Gandolfi, Razib Khan, Bronwen L. Aken, Steven M. J. Searle, Patrick Minx, et al. “Comparative Analysis of the Domestic Cat Genome Reveals Genetic Signatures Underlying Feline Biology and Domestication.” PNAS. National Academy of Sciences, December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Ottoni, Claudio, Wim Van Neer, Bea De Cupere, Julien Daligault, Silvia Guimaraes, Joris Peters, Nikolai Spassov, et al. “The Palaeogenetics of Cat Dispersal in the Ancient World.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group, June 19, 2017.

- ↑ Lassof, David. “How the Tabby Got Its Blotches.” Science. Accessed December 8, 2021.

- ↑ “The Domestic Cat.” Felis Catus. Accessed December 8, 2021.

- ↑ “Doctor's Warning: A Cat's Bacteria Is Worse than Its Bite | CBC News.” CBCnews. CBC/Radio Canada, December 4, 2016.

- ↑ “Zoonotic Disease: What Can I Catch from My Cat?” Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, July 23, 2018.

- ↑ Kates, Ashley E, Omar Jarrett, Joseph H Skarlupka, Ajay Sethi, Megan Duster, Lauren Watson, Garret Suen, Keith Poulsen, and Nasia Safdar. “Household Pet Ownership and the Microbial Diversity of the Human Gut Microbiota.” Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. Frontiers Media S.A., February 28, 2020.

Edited by Katianna Blackwell-Scott, student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2021, Kenyon College.