Cryptococcus gattii

Classification

Eukaryota; Fungi; Basidiomycota; Tremellomycetes; Tremellales; Cryptococcaceae; Cryptococcus [1].

Introduction

Cryptococcus gattii is a fungal pathogen originating in Australian eucalyptus and almond trees [2]. that has been known to cause respiratory failure and serious central nervous system complications when infecting a human host [3]. Although the pathogenicity of C. gattii has in large part already been investigated, the global distribution of the microbe is unclear because strains of the fungus have only been found in places where samples are tested - areas of high-incidence [4]. This yeast is endemic in parts of Australia, and is normally found in tropical and subtropical areas. However, it has recently been identified as the cause of a cryptococcus outbreak in British Columbia and parts of the American Pacific Northwest [2]. C. gattii is a leading cause of pulmonary cryptococcosis, basal meningitis, and cerebral cryptococcomas whose emergence, it has been suggested, is a result of changing climate conditions [5].

Genome structure

C. gattii has four main genetic groups (VGI, VGII, VGIII, VGIV); each of these genetic groups has 14 distinct chromosomes. Among these four genetic groups, the majority of genes are collinear, meaning that the same genes are found in the same locations on each of the chromosomes [2]. Amongst these four main groups, there is no evidence of any nuclear exchange. This is indicative of three separate but related species [6]. Sequencing of the mitochondrial genomes of VGI and VGII show adequate sequence similarity to suggest uniparental mitochondrial inheritance, but evidence of virulent traits between these distinct species in laboratory settings indicates that the transfer of mitochondrial genomes between species is possible [6]. 58 different genes located on 68 loci have been identified as showing divergent patterns of copy number variation amongst these 4 genetic groups [7]. The genome contains the CAP59 gene, which encodes the polysaccharide capsule, the LAC1 gene, which is involved in melanin synthesis, and the PLB1 gene, which encodes proteins that allow the yeast to invade host cells, among other proteins [2].

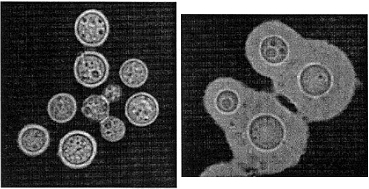

Cell structure

The cell diameter of most C. gattii cells typically ranges from 3-5 micrometers [3]. Most cells are roughly circular in shape, although it is capable of changing the size and shape of its capsule to avoid an immune response. C. gattii has a polysaccharide capsule, which is its main virulence factor [3]. C. gattii is typically found in the yeast form. It typically reproduces through asexual budding in both the environment and inside human hosts once an infection has occurred [2]. It is possible for sexual reproduction to occur. Cells can also undergo a dimorphic transition to hyphae to create a mycelium and generate basidiospores [2].

Metabolic processes

Creatinine deiminase is expressed in C. gattii in presence of creatinine; unlike its close relative C. neoformans, this enzyme is not repressed by the presence of ammonia in C. gattii [8]. Carbon sources include glycine and dicarboxylic acids. 94% of C. gattii strains are able to use D-alanine as the sole source of nitrogen for the cell. However, very few strains are able to utilize L-phenylalanine and none of the strains are able to use L-tryptophan as a nitrogen source [8]. When cultured in vitro, C. gattii display a characteristic abundance of the disaccharide α,α-trehalose, which allows for easy identification of the fungal growth in vivo [2].

The presence of the enzyme laccase has been detected in many strains of C. gattii. Laccase is responsible for the production of several different molecules that are important to the virulence of the yeast [2]. First of all, laccase promotes the production of melanin, which aids in energy production via oxidative phosphorylation [2]. Laccase also promotes the production of phospholipase B and urease, both important enzymes for the invasion of host tissue during infection. Lastly, laccase is responsible for the production of two antioxidants, trehalose and superoxide dismutase [2].

Ecology

Originally, C. gattii was only found in tropical and subtropical areas, like Australia and Southern California [3]. However, it has recently been found elsewhere, including the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Vancouver, Canada [9]. The fungus’ preferred environment changes depending on where it is found, which is how it has been found to survive in both tropical and temperate locations. It has been isolated in many places, including soil and man-made objects, like tires [9]. It can also live in seawater or freshwater for up to a year [9]. Plant material can promote the yeast’s fertility and possibly make it more pathogenic. The yeast are normally confined to individual trees because it has limited dispersal [2].

Pathology

C. gattii has been known to infect humans and animals to cause cryptococcosis [9], though it is uncommon in children [2]. There is a higher mortality rate in men, older patients, patients with a history of convulsions, and immunocompromised patients [2].

It is not passed human to human nor by a vector, therefore it is impossible to completely prevent its spread [10]. The host is infected when fungal spores are inhaled [9] and penetrate lung tissue [2]. If the spores enter the bloodstream, they can travel to other organs. Because the central nervous system and the lungs are normally affected, neurological and pulmonary symptoms are common [2]. The incubation period has a median of 6-7 months, but it can range anywhere from 2 weeks to 35 months [2]. C. gattii was originally found only in immunosuppressed people, but it has now been found in people with healthy immune systems [10]. When it reaches the lungs, C. gattii causes inflammation. In order to evade phagocytosis by the host’s macrophages, the fungus can decrease its diameter and change its capsule [3]. Common neurological symptoms of meningoencephalitis caused by C. gattii are seizures, blurred vision, and neck stiffness [10].

In the past, imaging has provided the first clues of of C. gattii infection. Among the most useful are radiographs and CT scans of the chest and MRI images of the brain [11]. Reliable specimens for diagnosis include bronchial washings, fine needle aspirates, and occasionally sputum. The presence of Cryptococcus species may be detected through a fungal stain known as calcofluor white, Gram staining, muscarmine stains, and India ink stains [11]. However, only culturing the fungus can lead to a confirmed identification of species and variety. Cryptococcus species can be isolated on blood agar plates, as well as several different selective enriched media [11]. For example, C. neoformans and C. gattii may be distinguished from other Cryptococcus species through the use of potato dextrose and birdseed agars, and may be distinguished from one another based upon the usage of the amino acid glycine and susceptibility to canavanine [11].

Several different factors affect the virulence of C. gattii; the primary factor is the presence of the polysaccharide capsule. Other factors include its capability of growing at 37°C, and the presence of the enzyme laccase [3]. The yeast’s virulence, along with the amount of exposure, the strain or genotype of the yeast, and the strength of the host’s immune system determine the outcome of the infection [2].

C. gattii infection is normally treated with amphotericin B or 5-flucytosine [2]; patients presenting with pulmonary symptoms may also be treated with fluconazole [11]. However, there is not a specific protocol for treating C. gattii because of the lack of randomized control trials and its relatively recent appearance in the U.S [11]. C. gattii tends to have a slower response to any intervention, more relapses, and relatively more severe symptoms compared to other Cryptococcus species. Therefore, clinicians have treated C. gattii infections more intensely than its relative C. neoformans [11].

Current Research

Current research on C. gattii has focused on understanding its pathology and where outbreaks are likely to occur. A recent study published by Costa et al. was the first to examine the link between the microbiota of the large intestine and the body’s immune response to C. gattii [3]. Germ-Free (GF) mice without a functioning microbiome had a decreased ability to combat the infection, while the conventional (CV), conventionalized (CVN), and LPS-stimulated mice with microbiomes all had a greater immune response to the infection which led to higher survival rates [3].

Recent research has also explored the effect that copy number variants (CNVs) have on genetic differences and increased virulence between strains [7]. CNVs contributed greatly to differences in transport, cell wall structure, and the capsule structure. All of these effects contributed to an increased virulence amongst C. gattii strains [7].

The CDC has been examining the occurrence and potential spread of C. gattii through the United States to predict where outbreaks may occur. Strains VGIIa, VGIIb, and VGIIc have been causing cryptococcosis infections in the Pacific Northwest, even though the U.S. was previously believed to be outside the normal climate range [10]. There was no clear route of introduction, but agricultural products were the most likely mode of transport. In past cases in North America, C. gattii has caused neurological problems such as seizures and headaches [10].

A recent CDC study determined that C. gattii is also endemic to regions in the Southeastern United States as well as the Pacific Northwest [13]. VGI and VGIII strains were found in the southeastern states and were found to have more single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) than strains from the Pacific Northwest. Due to the increased diversity in the VGI and VGIII strains, it was concluded that the southeastern C. gattii strains are older than the northwestern strains [13].

Other

2000-2001 Outbreak: Between January 1999 and December 2001, an outbreak of cryptococcosis occurred in British Columbia [12]. Approximately 38 cases of human cryptococcosis were recorded; all were caused by C. gattii . 95.2% of these human cases were identified as the VGII strain, and the remaining case was identified as VGI [12]. All isolates from environmental samples were identified as the VGII strain, which was determined to have caused this outbreak in British Columbia. British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest are both new locations for this microbe; C. gattii was previously found only in tropical and subtropical locations [12].

References

[1] Cryptococcus gattii VGI. Retrieved October 21st, 2016

Edited by Maris Wilkins, Christina Yuen, Michelle Crough, Arjun Malhotra, students of Jennifer Talbot for BI 311 General Microbiology, 2016, Boston University.