HIV/AIDs in the U.S.

By J. Sebastian Chavez-Erazo

An Introduction to HIV/AIDS

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a harmful retrovirus that, if left untreated, will lead to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) in humans. HIV works by attacking specific cells in the immune system: CD4 cells or T cells1[4]. HIV destroys these immune system cells enough over time that the body can not protect itself against infections and disease. The final stage of HIV infections is characterized by AIDS where the immune system is damaged enough that it becomes vulnerable to opportunistic infections. An opportunistic infection or a combination of them which then finally are the most likely cause of death in AIDS patients. If left untreated, individuals living with AIDS who are diagnosed with an opportunistic illness have a life expectancy of about one year1[5].

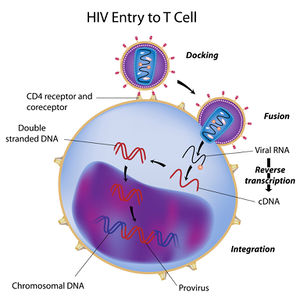

The origin of HIV has been identified as coming from a type of chimpanzee in West Africa where the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) was most likely transmitted to humans via contact with chimpanzee blood1[6]. SIV then mutated into HIV in human hosts and was transmitted from person to person via bodily fluids (blood, semen, rectal fluids, breast milk etc.) until the virus became spread worldwide over a couple decades. HIV is known to have existed in the United States as early as the 1970’s shortly before the AIDS epidemic of the 1980’s1[7]. The mechanism by which HIV infects T cells is similar to most retroviral infections: the virus inserts its viral RNA into the host white blood cell’s nucleus after attaching and has copies of itself made through a process called reverse transcription. In reverse transcription, an enzyme reverse transcriptase makes cDNA copies of the viral RNA using the host cell’s nucleotides which are then integrated into the genome of the host cell where the virus can become active or latent.

Over time, the continued production of HIV in CD4 cells causes AIDS to occur. AIDS is diagnosed in HIV positive individuals by a CD4 cell count1[8]. If an individual’s CD4 count falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood (200 cells/mm3) then they are considered to have AIDS1[9]. A typical CD4 count in noninfected adults is between 500 and 1600 cells/mm31[10]. An individual may also be diagnosed with AIDS if they acquire one or several opportunistic infections, regardless of their CD4 count.

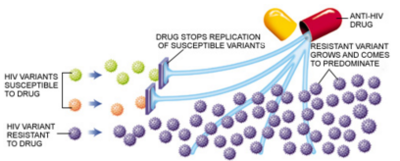

Treatment for HIV/AIDS has made leaps and bounds since the devastating AIDs epidemic of the 1980’s. Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, an HIV/AIDS diagnosis meant certain death. This was especially true for HIV positive individuals in the queer community who faced not only a lack of medication and treatment but also varying levels of social stigma and discrimination. Among the queer community, those most often affected by HIV/AIDS have been men who have sex with men (MSM), a trend which remains true in the present day. In the 90’s the introduction of antiretroviral treatment (ART) drugs which targeted the enzymes that make the process of HIV replication became available, with varying levels of efficiency and toxicity. It was soon after found that these antiretroviral drugs which inhibit different steps in the HIV replication process, were most effective if used as a cocktail. The use of several ART’s together was found to be most effective because of HIV’s great likelihood to mutate and become drug resistant due to the inefficiency of reverse transcriptase to make exact cDNA copies of the viral RNA. Today, there are four general categories of ARV medications: Nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI’s), protease inhibitors (PI’s), and drugs that interfere with viral entry such as fusion inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists2[11]. While there is still no cure or vaccine for HIV, the main goal has moved from treatment to prevention with the emergence of pre- and post-exposure prophylactic treatments where a daily regimen of a three-drug pill can be taken to decrease risk if HIV infection by up to 90% in high risk individuals. While these drug treatments and preventative measures now exist that make living with HIV/AIDS more like a chronic illness, issues of availability and public education present challenges to the fight against HIV/AIDS7[12].

A Basic explanation of Antiretroviral Treatments

Antiretroviral treatment is better defined as a therapy since the drugs used do not eliminate HIV from the body, rather they inhibit the HIV replication process and therefore slow down the effects of AIDS related infections and death. The replication of HIV in an HIV positive individual with a non-resistant strain can be suppressed in about 80% of cases where the individual takes the appropriate antiretroviral treatment as directed2[13]. There are, however, several side effects in ARV treatment and the potential for the drug treatment to not work effectively so the therapy process is not without fault. Another factor that can affect the efficacy of antiretroviral medications is adherence to the prescribed regimen—the likelihood of HIV resistance to antiretrovirals increases if individuals do not take the medication as directed, usually by only taking the medication intermittently or occasionally2[14].. ARV’s stop the immediate effects of HIV and reduce the risk of AIDS related conditions such as rare illnesses and cancers caused by opportunistic infections.

Antiretroviral medications are a group of different drugs that alter the HIV replication process by inhibiting different steps of the process. This medication never completely eliminates HIV infection from the body rather it suppresses the HIV infection. HIV targets infection-fighting immune CD4 cells specifically by binding to receptors (such as CD4, CCR5, and CXCR4) on their cell surface2[15]. After attachment, the viral RNA is put into the cell cytoplasm, a cDNA copy is made from the viral RNA by reverse transcriptase and then moved into the cell nucleus where it is incorporated into the human DNA by enzyme viral integrase. Antiretroviral drugs stop different steps in this infectious process, specifically targeting reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease2[16]. The four categories of antiretroviral medications are: Nucleoside and nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI’s), protease inhibitors (PI’s), and drugs that interfere with viral entry such as fusion inhibitors and CCR5 antagonists2[17].

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI’s) were the first line of antiretroviral medications allowed for HIV treatment in the U.S. They work by inhibiting viral reverse transcriptase, therefore blocking the HIV replication cycle. When used alone these drugs actually contribute to the evolution of drug resistant HIV strains and therefore must be used along with other drugs2[18]. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI’s) have chemical structures that are similar to NRTI’s, with their biggest difference being the location of binding they have to the viral reverse transcriptase enzyme in order to hinder the HIV replication process2[19]. Protease inhibitors target the HIV protease which stops the production of new HIV in human cells with the viral cDNA already integrated into its own DNA. Like NRTI’s, protease inhibitors can lead to disastrous drug-resistant strains of HIV if taken with no other antiretroviral medications so they are often taken along with NRTI’s and NNRTI’s2[20]. Protease inhibitors are also often supplemented with the drug ritonavir which slows down the breakdown of protease inhibitors and therefore prolong their activity2[21]. More recent research into ART drugs has found drugs that interfere with HIV entry into human cells as well as integrase inhibitors2[22].

.

Pre-/Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

In recent years, pre-exposure and post exposure prophylactic treatments for populations at high risk for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection have become increasingly studied and emphasized as vital to the decreased transmission rates of HIV resulting in decreased rates of Advanced Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) development3. Pre-exposure prophylactic therapy is indicated for those at high risk for HIV infection so that the rate of infection is lowered in high risk populations. Post-exposure prophylactic treatments are indicated for use immediately after an exposure to HIV, for example a needle stick with the blood of an infected patient or condomless sex with an HIV infected individual.

Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

PrEP has given a specific population the opportunity to have a 90% reduction in the chance of contracting HIV with the use of the daily pill, Truvada (oral emtricitabine (FTC)/ tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF))10[23]. The product is said to be available to any person regardless of their sexual and gender identity. Truvada was only approved for use as PrEP in 2012 but was approved for use as an HIV treatment drug in 200410[24]. PrEP is not meant to be taken alone to decrease the likelihood of HIV infection rather it is meant to be used as a part of a comprehensive HIV prevention regimen that includes correct, consistent use of condoms, regular HIV testing, treatment of any other sexually transmitted infections, and counseling on safer sex practices in some individuals. Adherence to the treatment regimen is vital to lower risk of infection10[25].

There are several qualifications an individual needs in order to be considered as a candidate for the use of Truvada and several factors taken into consideration in weighing the rusk versus the benefit. Most importantly the person must be HIV negative since the use of the two drug regimen in Truvada for a HIV positive individual would lead to drug resistance10[26]. The health status of the person is also taken into account, specifically if the person displays flu-like symptoms characteristic of acute HIV infection. Those with recent acute HIV infection most often present with flu-like symptoms and can fall under a test window for HIV diagnostic tests where the levels of antibodies that determine HIV infection are still not detected by the test. Safety concerns regarding Truvada’s effects on the bones and kidneys of potential candidates are also taken into account because of several inflammatory side effects common to most antiretroviral medications10[27]. Finally, the individual must also be negative when tested for Hepatitis B because worsening of hepatitis B infections has been reported in those who have both HIV and hepatitis B when treatment with Truvada was stopped10[28].

.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

PEP presents the same two drugs used in Truvada for PrEP with the addition of a third antiretroviral drug because of possible HIV infection after a high risk incident occurred. Typically, someone who has just had a high risk incident occur is put on a PEP regimen for a range of four to nine weeks in hopes of deterring HIV infection and integration of viral DNA into human genome. The third drug added to the two drug regimen is chosen based on the specific needs of the patient. The population most at risk for HIV infection in the United States is MSM but PEP and PREP have been shown to be effective in the prevention of HIV infection in several populations, and being surprisingly effective in women through the investigation of antiretroviral drug genital tract concentration in women8[29].

Challenges to HIV/AIDs Prevention and Treatment

In the 1990’s antiretroviral treatment completely changed the course of HIV infected individuals’ lives changing the death sentence to a relatively treatable lifelong chronic condition. In recent years there have been new findings in preventive measures and drugs for HIV infection yet the rates of HIV infection have remained steady in the past decade, a trend the FDA deems unacceptable10[30]. The problem being faced now is not a lack of therapeutic and preventative measures, instead it is the knowledge of and use of these measures that has kept the rates of HIV infection in the United States consistent.

Limited education regarding PrEP and PEP in high risk populations remains one of the key problems in preventing new HIV infections. Among those at highest risk for HIV infection, MSM, PEP awareness and use was modest as was PrEP use—a finding suggesting increased community education on the availability of PEP7[31]. Public education regarding safe sex practices continues to be a point of weakness in prevention of HIV infection as well. While populations need to be made aware of the existence of PEP and PrEP, knowledge is not enough. Many social and psychological aspects of PEP/PrEP use come into play as well. Specifically, in populations of MSM, those living in more stigmatizing environments had decreased use of antiretroviral-based HIV prevention methods compared to those in less stigmatizing environments9[32]. These findings present the need for new approaches to the presentation of these medications and further education of the existence and implications of taking PEP/PrEP.

HIV prevention must then move into including biobehavioral aspects for increased efficacy. Recently the importance of tailoring adherence counseling to address psychosocial factors and mental health stressors that negatively affect adherence has been emphasized3[33]. Another aspect of preventative measures under scrutiny is the difficulty regarding requirements for PrEP use. There are arguments for reconsidering how to best predict a person’s risk of HIV infection and then when the best optimal time is for them to initiate PrEP as well as monitoring and counseling services3[34]. While there are many arguments for increasing the use of PrEP an PEP in preventing HIV infections, there are also drawbacks to having larger populations of people taking two anti-retroviral medications regularly: drug resistance. The main concern is starting PrEP in people already infected with HIV since this often leads to drug resistance6[35]. There are however also arguments against this claiming that preventing HIV infection is also preventing drug resistance6[36].

Conclusion

References

[2] Virtual Medical Center. "Antiretroviral Therapy (Anti-HIV Drugs)"

[11]

Authored for BIOL 291.00 Health Service and Biomedical Analysis, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2016, Kenyon College.