Hypsibius dujardini

Classification

water bear[8]

Higher Order Taxa

Domain: Eukarya

Phylum: Tardigrada

Class: Eutardigrada

Order: Parachaela

Family: Hypsibiidae

Species

|

NCBI: [1] |

Hypsibius dujardini

Discovery of Tardigrades

Tardigrades were discovered first in 1773 by German zoologist Johann August Ephraim Goeze and named them little water bears

. Later, in 1777, they were renamed Tardigrada

by Italian biologist Lazzaro Spallanzani. This new name carried the meaning slow steppers

[7].

Description and Significance

H. dujardini is a freshwater species of Tardigrade (also known as water bears

) found in the algae and sediments of rivers, streams, and lakes [2], and is cosmopolitan in nature, being found in many different environments around the world. They have been found to survive in a multitude of environments and are one of the most resilient animals on Earth, placing them in the category of extremophiles. They have the ability to survive in extreme high and low temperatures, extreme high and low pressures, deprivation of air, starvation, dehydration, radiation, and have even been found to survive in outer space [7]. Geographically, they have been found in the Palearctic, Neotropical, Nearctic, Afrotropical, Antarctic, and Indomalaya regions, and are the most commonly found tardigrade in the Nearctic region [2].

Appearance

H. dujardini are approximately 0.50mm in length and have long, plump bodies with 8 legs, with claws on the end of each, lined symmetrically down the length of their bodies [2]. To distinguish H. dujardini from other species of tardigrade there are three main features to observe:

- There are eight morphologically different claw sets used when comparing tardigrades to determine its species. For H. dujardini, their claws are two branched that differ in length and face opposite each other within each pair [2].

- Their apophyses for the insertion of the stylet muscles (AISMs) appear to be more hooked [2].

- Their waxy cuticle is much smoother in appearance compared to other tardigrade species [2].

Additionally, females often appear to be larger than the males [2].

Significance

H. dujardini is one of the best studied species of tardigrade and has been important to use as a model for studying the evolution of development [4]. Additionally, they have been used in a study that observes the effect of taking away a geomagnetic field on the mortality rate of H. dujardini [3]. This study addresses the question of terrestrial organisms having the ability to travel through space and colonise on new planets, including organisms from Earth.

Genome Structure

There have been three genome assemblies for H. dujardini where they were able to determine that the median total genome length is 182.155 Mb, the median total protein count for their genome is 20853, and the median GC% for the genome is 44.5 [5].

Metabolism, Life Cycle and Survival

Metabolism

The metabolic rate for H. dujardini has not been studied or reported on, however it has been found that the oxygen consumption rate of another freshwater, moss-dwelling tardigrade, known as Macrobiotus hufelandi, when in an active metabolic state is (980μl x 10^-6)/hour [2]. It can be assumed that the metabolic rate of H. dujardini could be similar.

Reproduction and Development

There is no known information on the mating habits of H. dujardini, but sexual reproduction is often undergone as there are usually both male and females in a population [2]. However, when sexual reproduction is not a viable way to produce offspring, meiotic parthenogenesis can occur. This is when a haploid egg returns to diploid through the duplication of chromosomes [2]. Molting (shedding of claws, waxy cuticle, and hindgut) occurs throughout the lifetime of H. dujardini, approximately 4-12 times and can take between 5-10 days to complete each time, and is an important part of reproduction [2]. Females can lay between 3-4 eggs on average each reproductive cycle and will lay these eggs in the shed from their molt to undergo development for 4-4.5 days before hatching [2]. It has been found though that eggs developed in a laboratory take 13-14 days to hatch [2].

Dietary Habits

There have been no experiments on H. dujardini involving testing where they receive their nutrients from, but it can be assumed that since other moss-dwelling tardigrade have been found to feed on algae, H. dujardini would be the same [2].

Survival abilities

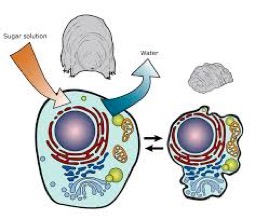

The survival ability of H. dujardini is due to their incredibly effective environment stress response of undergoing cryptobiosis (more specifically known as, and driven by, anhydrobiosis) and induced by desiccation when conditions become unfavourable [2]. Anhydrobiosis is when they become ametabolic and dehydrated to survive extreme environmental stressors until the conditions become favourable again and they come into contact with water which the stimulates desiccation emergence [2]. They can survive in this state for varying lengths of time, with a 120 year old, unidentified species of tardigrade was observed going through desiccation emergence when some moss was rehydrated [2]. Typically though, when not under a desiccated state, H. dujardini have been predicted to live anywhere from 4-12 years in the wild [2].

Ecology and Pathogenesis

Pathogenesis

There is no known pathogenesis linked to H. dujardini.

Known Symbiosis

A parasitic fungus called Ballocephala pedicellata has been found to use H. dujardini as an important part of their reproduction, using them as a host [2]. This symbiotic relationship occurred to H. dujardini living and eating within the vicinity of Ballocephala pedicellata which naturally allows for cohesion and encystment from the fungus to H. dujardini [2]. After cohesion and encystment, conidospiores (a form of asexual spores) are produced by Ballocephala pedicellata and continual fragmentation occurs within the tardigrade. Zygotes that have been produced by Ballocephala pedicellata remain dormant within H. dujardini as they fused with the cell wall of their new host [2].

References

[1] Contributor, Alina. "Facts About Tardigrades." livescience.com. N. p., 2017.

[2] "Hypsibius Dujardini." Animal Diversity Web. N. p., 2020. Web.

[5] "Hypsibius Dujardini (ID 768) - Genome - NCBI." Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. N. p., 2020. Web.

[7] "Tardigrade." En.wikipedia.org. N. p., 2020. Web.

[8] "Hypsibius Dujardini." En.wikipedia.org. N. p., 2020.

[9] "3 Waterbears By Banvivirie On Deviantart." Deviantart.com. N. p., 2017. Web.

[10] Marley, N., McInnes, S. and Sands, C., 2011. Phylum Tardigrada: A Re-Evaluation Of The Parachela.

Author

Page authored by Rosie Munro, student of Prof. Jay Lennon at IndianaUniversity.