Meningitis and Effects on Epilepsy

Introduction

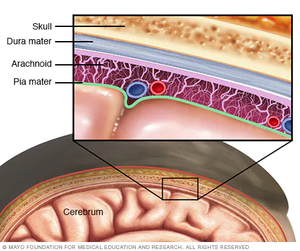

Meningitis is an infection that results in the swelling of the meninges (membranes) and fluid of the spinal cord and back.[1] The severity of acute infection can vary from person to person. In some cases, the bacteria die off on their own and the infection fades away after a few weeks. In other cases of meningitis, immediate hospitalization is required with the treatment of IV antibiotics. [2] However, the severity of a person’s meningitis case can vary with the mode of infection as well. There are as many as 6 different ways to contract meningitis but the most common ways are through a virus, fungus, and bacteria. Fungal infections of meningitis are rarer and fungal and viral infections cause fewer complications and are easier to treat.[3] As always, younger and immune-compromised persons have a higher risk of serious complications with this infection. Unfortunately, not all symptoms and side effects of this disease are short-term. Long-term neurological issues such as learning disabilities, narcolepsy, and even epilepsy are being discovered and researched.

Epilepsy, also known as the “chronic seizure disorder”, is exactly what the name implies. It is a disorder that is characterized by a person experiencing unprompted and reoccurring seizures.[4] Many affected people will experience a variety of seizures including but not limited to tonic, clonic, and absence. Tonic seizures are when the muscles in the body freeze up and become stiff, clonic seizures are characterized by uncontrolled jerking movements, and absence seizures are lapses in a person’s awareness or consciousness for short periods of time. When combined together, Tonic-Clonic seizures are also called Grand Mal.[5][6] Epilepsy is known to have several different causes such as genetic abnormalities, brain injury, and defects in development. However, recent studies show that brain infections, such as meningitis, are becoming a much more prevalent cause of epilepsy.[7]

Continued research into this growing field of long-lasting effects of brain infections has furthered the understanding of their effects on different parts of the brain, including those that affect epilepsy. The link between these two health problems is becoming increasingly more clear as linked cases continue to rise every day. Current information suggests and proves that meningitis patients have an increased risk of developing epilepsy than those who have not contracted meningitis.[8]

Viral Meningitis

Viral meningitis is the most common form. It is most often caused by non-polio enteroviruses. These can include mumps, Epstein-Barr, influenza, measles, and others. Fortunately, only a small number of those infected with any of the above viruses will contract meningitis as a result. The contagion of viral meningitis is determined by the contagion of the virus causing meningitis. However, before current medications and vaccines, once contracted, there was a 30-40% chance of developing meningitis from any of the above viruses. Now, here is only a 5-10% chance (varies by virus).[9]

While common symptoms can vary based on age, there are similarities in patients of all age groups. These are fever, headache, poor appetite, photophobia, sleepiness, vomiting, and lethargy. As with most viral infections, there is no specific treatment such as antibiotics. If someone is seriously ill and needs to be admitted to the hospital, they will most likely have their symptoms treated and monitored. Approximately 10-15% of infected individuals need emergency hospital care.[10]

Bacterial Meningitis

Bacterial meningitis is the second most prevalent form of meningitis. It is also the most deadly form. It is fact acting and can cause serious paint throughout the entire experience. Some who contract this are unlucky enough to be affected for a few weeks while others pass within a few hours of contraction.

Just like viral meningitis, there are multiple different pathogens that can cause the bacterial form such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Group B Streptococcus, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenza, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. [11] Group B Streptococcus can be spread mother to child during birth or breastfeeding. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenza, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis are spread through physical contact with body fluids such as spit or by breathing in the pathogens. E. Coli can even cause bacterial meningitis when contracted from a food source.[12]

The signs and symptoms are similar if not identical to viral meningitis. However, patients can also experience early-onset seizures and the treatment is different. For bacterial meningitis, IV antibiotics are a possibility. Most patients are also given steroids for brain swelling, oxygen in case of lung complications, and other IV fluids for dehydration. For those patients who do experience seizures during the course of their infection, the infection is treated first while trying to control the seizures. Scans and treatment for the seizures occurs later after the patient is stabilized.

There are vaccines as well to prevent the spread and contraction before it begins. In the late 1990s to early 2000s, the rate of death from meningitis was almost 30% and the hospitalization rate was as high as 90% for some original pathogens. It is now down to about 10% for the death rate and an average of 30% for hospitalization.[13]

Fungal Meningitis

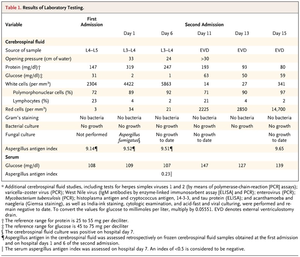

The final form of meningitis is fungal meningitis. The least is known about this form as it is the rarest to contract. This is caused by a fungus entering the body of an immune-compromised individual. This can include those with chronic illnesses, cancer, HIV, and more. The symptoms are similar to those of the viral form but also may contain a skin rash and spotting. This form affects blood cell counts as well. Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Blastomyces, and Candida are all common fungi that can cause this form of meningitis.

Treatment and identification for this form depend on which fungi the meningitis came from. For example, in Histoplasma infections, itraconazole is used for 3-12 months while with Blastomyces infections amphotericin B is used for 6-12 months. This form is in between the viral and bacterial forms in severity and likely hood to be hospitalized.[14]

Neisseria meningitidis and its Genome

Neisseria meningitidis is one final way to contract meningitis. It is typically found as a harmless bacteria in the human upper respiratory tract. Like most other bacteria mutations in the genome of certain strains and weaker host immune systems in the host can cause a form of bacterial meningitis. Unfortunately, the difference in the genome of dangerous and benign forms of N. meningitidis are so slight they are often not found until after infection. However, this bacteria is still constantly evolving and is in fact a recent, new species. As the differences in the genetics between strains are slight but powerful, this bacteria is being studied further to reveal its flexibility and ability to quickly adapt for survival.[15]

In 1990, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis showed that the structure of the N. meningitidis chromosome is widely variable. In fact, there are 7 known virulent variants of meningococcal bacteria. These are A, B, C, W, X, Y, and Z. Some of the differences between the invading strains and wild-type strains can be as small as a base substitution of an adenine (A) to guanine (G) in the ET-15 complex. Others can be as large as a deletion of the 40kb fragment that controls reproduction so as to not overrun the host.[16]

For N. meningitidis, this ability to create large or small mutations that have such powerful effects has benefits and consequences. It allows the bacteria to quickly adapt and grow when given a short time frame or limited space to do so. It also allows for this bacteria to create drug-resistant strains. However, this quickly evolving organism makes it easy to study mutations and how they can occur.[17]

Epilepsy

As mentioned in the introduction, epilepsy is a neurological disorder that causes an affected individual to have a multitude of different types of seizures seemingly at random. There are certain triggers, though, such as lights, sounds, and stress. There are four main types of epilepsy depending on where in the brain the seizures start. But, one person can be affected in multiple areas of the brain or just one. The seizures that affect more than one focal point are known as "generalized seizures" and epilepsy that is centered in multiple parts of the brain is considered "generalized epilepsy".[18]

Frontal lobe epilepsy is characterized by seizures starting in the frontal lobe. These mainly occur at night or during periods of rest. They are usually short and do not last much longer than one minute. Seizures that start in the frontal lobe often spread to or combine with other seizures from different parts of the brain such as the temporal lobe. These are the easiest to control with anti-convulsant medications.

Temporal lobe epilepsy happens to be the most common form of epilepsy. These start in the sections of the brain that are on the sides behind the temples. As this is the area most commonly affected, the temporal lobe is at risk for scarring and damage (which could require surgery) in most patients. Unfortunately, these seizures are not only the most powerful but have the largest effect on a patient’s life quality. These seizures often have symptoms of burning smells, strong emotions, chest pain, loss of consciousness, and muscle spasms and jerks.[19]

The third form is parietal lobe epilepsy. The parietal lobe is the part of the brain that encompasses the top and sides of a person’s head. As this is the part of the brain responsible for making sense of the information the brain is given, it is also known as the “association cortex.”[20] Here, the signals given by your fingertips, tongue, nose, and eyes are formed into physical sensations that we can perceive. As such, seizures here can have serious detrimental effects on the senses including hot flashes, hallucinations, numbness, tingling, and a drop in spacial awareness.

The final form of epilepsy is occipital lobe epilepsy. This form affects the occipital lobe, which is the section in the back of a person’s brain that is responsible for sight. Seizures in this part can cause momentary or long-term blindness, flashing bright spots, and other vision changes. Most patients with this form are extremely photophobic and have grand mal seizures when exposed. This is also the rarest form of epilepsy.[21]

Treatment of epilepsy usually starts with a multitude of scans such as MRIs, CAT scans, and sometimes PET scans to monitor scarring and damage to the frontal lobe. After, the patient is often put through rigorous therapy for a few months to strengthen and rebuild muscles that are damaged or weakened through seizures. Nine out of ten patients will end up on one or more AEDs, or Anti-Epileptic drugs. Continuous scans are necessary about every 6 months or as the patient's doctor decides is necessary. One out of 13 patients will end up with microelectrodes implanted to stimulate proper lobe function if they are not responding to medication. In extreme cases of frontal or temporal lobe scarring and damage, brain surgery is required to remove the affected parts as they could continue to get worse. Prognosis has continued to increase as seven out of ten patients live normal unaffected lives on medications and other forms of treatment.[22]

How Meningitis causes Epilepsy

A new field of research has exploded over the last few years. This field is researching how brain diseases can affect neurological disorders. According to a recent research study, as many as 35% of patients experience neurological disabilities after a meningitis diagnosis. The most commonly linked disease and disorder are meningitis and epilepsy. This is because the areas of the brain that controls body movements, such as the mesial portion of the temporal lobes, are affected by the swelling that occurs when a patient has meningitis. This side effect of the disease often does not appear until 6 months to 2 years after but can occur as early as 5 days after treatment. Seizures and epilepsy are also shown to be more common in those with pre-existing health conditions than otherwise healthy individuals.[23]

Recent studies show that the form of meningitis that epilepsy most often follows is the bacterial form. In fact, epilepsy can occur after meningitis contracted from S. pneumoniae 16-37% of the time. Patients whose meningitis came from H influenza, N meningitidis, or L monocytogenes can have a long-term side effect of epilepsy 5-26% of the time. Surprisingly, in patients who are directly infected with Neisseria meningitidis, epilepsy is shown to only occur 4-18% of the time.[24]

Unfortunately, new information suggests that the seizures that occur during infection that were previously thought to be a short-term symptoms are long-term 25-38% of the time. These acute seizures usually start as a response to damaged cerebral hemispheres due to swelling and fluid build-up in the brain during infection. Brain hypoxia, or the lack of oxygenated blood to the brain due to swelling, which occurs 7-22% in meningitis cases, is yet another cause for concern with seizures and long-term seizure disorders. Fortunately, the likelihood of survival of patients that experience acute seizures during treatment only drops 5%. [25]

Once fully recovered from their meningitis, the patient is pulled off of the original treatment and put through intensive therapy, screening, and medications to control the new disorder that has arisen.

Conclusion

Overall, through much research and dedication in the fields of neurological diseases and disorders, a clear link has been found between the patients with meningitis and their likelihood of developing epilepsy in the coming five years. This is a fairly new field of research that is just now expanding to look for different underlying connections and possible preventative measures. However, one thing that is for certain is that bacterial meningitis is the most common cause of epilepsy among the three main types of meningitis. The prognosis of meningitis patients is not noticeably harmed with early-onset epilepsy (seizures that occur within treatment time) but it is a growing cause for concern in the long run.

References

- ↑ [1] “Meningitis.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1 Oct. 2020

- ↑ [2] "Meningitis: Symptoms, Causes, Transmission, and Treatment.” WebMD, WebMD

- ↑ [3] “Meningitis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 Mar. 2022

- ↑ [https://www.epilepsy.com/learn/about-epilepsy-basics/what-epilepsy ]“What Is Epilepsy? Disease or Disorder?” Epilepsy Foundation, 21 Jan. 2014

- ↑ [4]“Types of Seizures.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 30 Sept. 2020.

- ↑ [5]“Absence Seizure.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 24 Feb. 2021.

- ↑ [6]“Epilepsy.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 7 Oct. 2021.

- ↑ [7]Vezzani, Annamaria, et al. “Infections, Inflammation and Epilepsy.” Acta Neuropathologica, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Feb. 2016.

- ↑ [8]“Viral Meningitis.” Mayo Clinic, Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 1 Oct. 2020.

- ↑ [9]“Meningitis from Viruses.” Meningitis Now.

- ↑ [10]“Bacterial Meningitis.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 15 July 2021.

- ↑ [11] “Bacterial Meningitis: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment & Prevention.” Cleveland Clinic.

- ↑ https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/meningitis/treatment/] “Bacterial Meningitis.” NHS Choices.

- ↑ [12]“Fungal Meningitis: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment, and More.” Medical News Today, MediLexicon International.

- ↑ [13]“Meningococcal Disease.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 7 Feb. 2022.

- ↑ [14]Buono, Sean A., et al. “Web-Based Genome Analysis of Bacterial Meningitis Pathogens for Public Health Applications Using the Bacterial Meningitis Genomic Analysis Platform (BMGAP).” Frontiers, Frontiers, 1 Jan. 1AD.

- ↑ [15]Schoen, Christoph, et al. “Genome Flexibility in Neisseria Meningitidis.” Vaccine, Elsevier Science, 24 June 2009.

- ↑ [16]“Generalized Seizures.” Johns Hopkins Medicine.

- ↑ [17] “Focal Epilepsy.” StackPath.

- ↑ [18]“Association Cortex.” Association Cortex - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics.

- ↑ [19] “Focal Epilepsy.” StackPath.

- ↑ [20]"Epilepsy Treatment Options" NHS Choices, NHS, https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/epilepsy/treatment/.

- ↑ [21]Shikha S Vasudeva, MBBS. “Meningitis and Epilepsy?” Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology, Medscape, 16 Nov. 2021.

- ↑ [22]Pomeroy, Scott L., et al. “Seizures and Other Neurologic Sequelae of Bacterial Meningitis.” New England Journal of Medicine, 14 Apr. 1970.

- ↑ [23]La Russa, Raffaele, et al. “Post-Traumatic Meningitis Is a Diagnostic Challenging Time: A Systematic Review Focusing on Clinical and Pathological Features.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences, MDPI, 10 June 2020.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2022, Kenyon College