Microbial Cardiac Infections

Introduction

Usually, when an infection is mentioned, the first thing that comes to mind is an open wound—cut, scrape, etc—that has gotten bacteria in it most likely because of improper care. However, infections can take place inside the body far from where the original entrance into the body is. Bacteria and fungi can make their way into the bloodstream and cause infections in different parts of the body including tissues and organs. For example, microbes that make their way into the blood stream can adhere to the lining of different parts of the heart causing infections. Because the components of the heart have no direct supply of blood, they are more prone to infection than other parts of the body because the immune system cannot reach them.

These microbes can enter the bloodstream in several different ways. Some of the most common ways include: bacteria in the mouth that enter the bloodstream during routine dental procedures and mouth bacteria that end up on the needles of drug users in the form of saliva, common skin bacteria that can also enter through the use of needles, bacteria that can enter the bloodstream through the rectum during colonoscopies or other rectal procedures, and many more.

An infection of the heart is termed endocarditis. Though other types of infections can take place in the pericardium and myocardium, endocarditis deals with swelling due to infections in the endocardium or inner linings of heart—ventricles, atriums, and most commonly valves [2].. There are many different types of predispositions that can make a patient more at risk for these infections, but in the majority of cases the mitral valve will become infected with the infection developing into a vegetation, causing many problems.

By Santiago Acero

Heart Overview

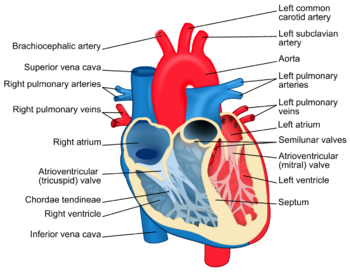

For efficiency we will begin by giving a brief overview of the heart and its components.

The heart as it is commonly known lies in the left side of a person’s chest. It is incased in a layer of tissue called the pericardium. The outer lining of the heart muscle wall is called the myocardium while the inside lining of the heart is the endocardium. The heart is divided into two sides, left and right. The left side of the heart composed of the left atrium (top) and ventricle (bottom), takes blood in from the lungs after being oxygenated. After coming in through the pulmonary veins to the left atrium, it will go to the left ventricle passing the mitral valve (common place for infection) and out through the aorta to be distributed to the rest of the body. The right side of the heart will take blood in through the superior and inferior vena cava into the right atrium, passing the tricuspid valve (common place of infection for drugs users) into the right ventricle and existing through the pulmonary arteries to be oxygenated and so on [3]. Figure 1. summarizes this information. Further information and more thorough overview available at [4].

Infective Endocarditis

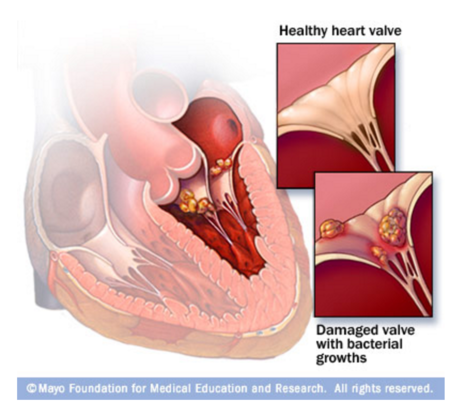

Endocarditis is defined by the swelling of the inner lining of the heart. Endocarditis caused by bacterial or fungal attachment and infection by means of developing vegetation, is therefore termed infective endocarditis [5]. Fig. 2. shows an example of an infected valve caused by infective endocarditis. As mentioned previously, the endocardium does not receive a direct blood supply by capillaries or any blood vessels. Blood will usually flow smoothly past the inner linings of the heart, but many things can cause attachment of microbes causing endocarditis. For example, any diseases that cause harm or result in abnormal valves, will allow the microbes that come through to attach more easily. For example, rheumatic fever and high blood pressure diseases will harm the endocardium. Consequently, these infections are hard to fight off because of the lack of direct blood supply; immune responses of the body, such as T-cells, will not be able to combat the infection and antibiotics will have a hard time reaching these places, as they commonly travel through the bloodstream.

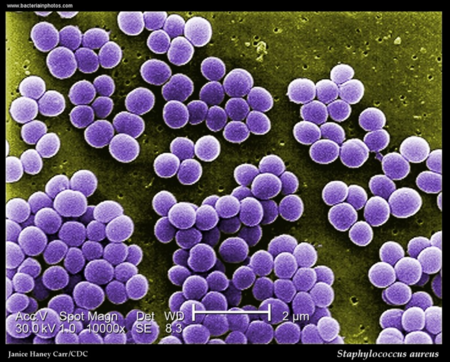

Commonly, endocarditis is classified as subacute and acute bacterial endocarditis [6]. The difference lies in the type of bacteria that cause the infection. For example, low virulence streptococci while have mild effects and will develop slowly over time extending to months. On the other hand, Staphylococcus aureus, a well known virulent pathogen that causes pneumonia, will act more aggressively and quickly in a time from of days and weeks. However, more recently these subcategories have been adapted to short (less than six weeks) and long (longer than six weeks) incubation periods. Furthermore, the bacteria that cause these infections may also take a long time to culture. Another way to classify types of infective endocarditis is the culture-positive and culture-negative method, though it has proved somewhat inefficient due to bacteria that are no easily isolated and cultured, causing misclassification of patients. Because of this, after diagnosis of infective endocarditis, patients are usually started on some antibiotic regiment [7].

Past these different types of classifying infective endocarditis, the location of the infection adds another dynamic to its category [8]. As discussed earlier, the infections will commonly take place on the left side of the heart on the mitral valve. However, in drug users who are injecting directly into their veins, ultimately ending up in the vena cava, will affect the right side of their heart and in term the tricuspid valve and will likely be caused by S. aureus. However, left sided endocarditis is still most common among drug users and non-drug users.

Another way in which infections in the endocardium arise is by nosocomial means, meaning that the infections takes place in a hospital setting. Patients prone to nosocomial infection normally have or have had heart transfers, valve replacements, artificial valves or other heart components, pacemakers, or intravenous catheters that are susceptible to infection by the bacteria found in hospitals and other health care facilities. In the case of artificial valve replacements, it is important to determine if the infection is early or late. Early infections are most commonly intraoperative or postoperative in the nosocomial category. If the infection took place later on, a year or so following operation or last hospital visit, it is a sing of a community-acquired infection. In either case, artificial implants are usually infected by Staphylococcus epidermidis, a common skin bacteria, because of its ability to develop biofilms on plastics [9]. This bacteria is also the cause of infections in catheters and respiratory machines.

Risk Factors

Thankfully, infective endocarditis is very unlikely in a patient with a healthy heart and good overall health. Bacteria that flow through the bloodstream will be cleared out very quickly in healthy patients. Studies have shown that only 5-7% of patients with a fever (common sign of endocarditis) in a hospital setting suffer from infective endocarditis [10]. Those who are more likely to acquire infective endocarditis will be patients who have had some type of heart surgery, including heart transplants and prosthetic valves and intracardiac devices such as pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, as mentioned above. As well, patients with a history of heart problems of any type are always at higher risk than those with non, even if no symptoms show [11]. Patients with congenital heart deficiencies are especially at risk of infective endocarditis. As mentioned in the opening section, chronic rheumatic heart disease also puts patients at risk, as it damages the endocardium and gives bacteria a higher chance at attachment. Other risk factors include autoimmune deficiency diseases such as diabetes and HIV. In patients with autoimmune deficiency diseases, normal concentrations of bacteria in the blood can build up causing a higher risk for attachment onto the endocardium resulting in infection. Alcohol abuse can also be a risk factor for infective endocarditis. As it has been discussed, any time that there is access to the bloodstream, infection is possible. Intravenous drug users are at risk because of this; studies have shown that 10-15% of patients with a fever in hospital settings will have infective endocarditis, a twofold increase from nondrug users. In addition, patients with colorectal cancer will also be at risk of bacteria entering the bloodstream and causing infection, mainly Streptococcus bovis [12]. Patients who suffer from serious urinary tract infections can also be at risk of infective endocarditis cause by enterococci.

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms of infective endocarditis vary, but there are common signs found in those infected. As it has been mentioned, fever is a common sign of infective endocarditis with 97% of those infected experiencing it, fatigue and a general feeling if malaise follow at 90% [13]. Other signs include a change or developed heart murmur—sounds made by blood rushing through the heart, in this case could be attributed to regurgitation of blood from an infected aortic valve—sudden weight loss, and a consistent cough, taking place in 35% of those infected. Other more common signs are Olser’s nodes (red, tender, subcutaneous spots in fingers), tenderness or enlargement of the spleen (as it is an organ involved in fighting off infections), Petechiae (very small red or purple dots on the skin and inside of mouth, called Roth’s spots when present on the retina), and more generally night sweats, shortness of breath, paleness, and swelling of extremities and abdomen [14].

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of infective endocarditis can be complicated because of its resemblance to other diseases in its early stages. Some common methods of diagnosis include looking for common symptoms coupled together. For example, a doctor may notice his patient suffering from a fever and when listening to his or her heart by use of a stethoscope, may find a developed heart murmur or a change in a previously noted heart murmur. When infective endocarditis is suspected, doctors are to follow the Duke criteria to determine whether or not the patient is suffering from the infection [15].

The Duke criteria is a method developed in the 1990’s to help improve the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. The criteria has proven to be effective in the past. Studies have looked at previously diagnosed patients with either definitive, probable, or rejected infective endocarditis using the Duke criteria and reevaluated the patients to test the effectiveness of the diagnosis. This study done by Dodds et al. found that the negative predicted value of Duke criteria was 92%, with no cases that were previously diagnosed as rejected showing otherwise. However, the Duke criteria has complications that arise from its source of accuracy. Its intricacy and complexity has proved difficult when dealing with evolving bacteria and hidden cases of infective endocarditis. As well, the criteria has not been kept up to date [16]. The criteria is largely dependent on echocardiography, which has proven to be a powerful diagnostic tool, and on a large complex set of guidelines. For example, for a patient to be diagnosed with possible infective endocarditis, the case must meet 1 major and minor criteria or 3 minor criteria. The major and minor criteria are broken down into different subsections with a variety of criteria each, adding to the complexity of the diagnosis [17].

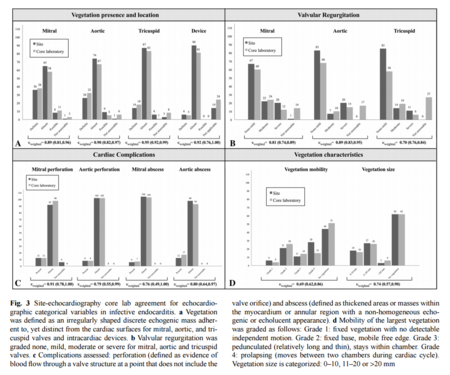

However, the use of an echocardiograph coupled with the criteria (based on symptoms and tests) has proven effective. Echocardiographs have been proven to be very powerful tools when diagnosing infective endocarditis. A recent study looked at how effective diagnosis using echocardiography was and what its reproducibility was. As well, this study introduced new methodological procedures for ensuring that the diagnosis was as accurate and reproducible as possible. The team of researchers used an observational cohort of data. It was seen that “Substantial or almost perfect intra- and inter-observer agreement was observed for most echocardiographic variables in the diagnostic assessment of infective [endocarditis]” [18]. Most importantly observer agreement was the largest in diagnosis of the vegetation location and existence. Figure 3. shows the high level of agreement in both non-native and native infective endocarditis, the graph shows comparative agreement of the cohort regarding different aspects of infective endocarditis diagnosis. Other common modes of diagnosis include the use of blood tests. Blood tests help doctors see if bacteria are present in the blood, in what concentrations, and what types. As well, the count of red blood cells can be a telling sign of infective endocarditis. Electrocardiograms also help physicians get a better look at patients’ hearts. This tool measures the electric activity of the heart when an irregular heartbeat is noted. This helps take a closer look at each heart beat and all electric activity of the heart. Chest X-rays are also helpful tools as infective endocarditis often cause swelling of the heart, visible in this test. When infection is suspected to have spread to other parts, X-rays can show its effects on the lungs. For possible infection spreading to other parts of the body, scan/ magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computerized tomography (CT) are two common tools to help doctors visualize the rest of the body and check for infections.

Causes

It has been mentioned broadly and indirectly how infective endocarditis takes place. We will now go into detail of the key players involved in the causation of this type of infection. Infective endocarditis takes place when microbes enter the blood stream and attach themselves to abnormal or damaged valves of the heart creating vegetations that cause problems. Though most commonly these infections are cause by bacteria, fungi and other germs may cause the infections as well [19]. The way in which the microbes gain access into the blood stream give clues as to how the infection should be treated, as well as giving doctors a better look into social hygiene problems. Infective endocarditis can be caused by something as simple as brushing your teeth or flossing your gums; even mastication can be a cause. Generally, this is seen in people who do not have healthy teeth and gums. Bacteria can also gain access through any sort of breach in the skin. This includes skin sores, gum disease, and sexually transmitted infections [20].

Furthermore, bacteria that generally comprise the microbiota can become harmful if they somehow gain access into the blood stream, as in the case of inflammatory bowel disease or other intestinal disorders. In related fashion, medical procedures that cause the breach of the epidermis can also cause infection. For example, catheters and needles used for vaccines, intravenous medicines, blood drawings, and intravenous drug use. However, it is often ignored that needles involved in piercings and tattoos can also lead to infective endocarditis. And as mentioned, certain dental procedures can also put patients at risk of infection [21]. However, in the overwhelmingly majority of cases, bacteria that enter the body are destroyed by the immune system; even in cases that the microbes reach the heart, they merely pass by without causing any complications of any sort. In any case, it is possible for a completely healthy person with a healthy heart to become infected, it is just much, much more unlikely.

The most common types of bacteria causing infective endocarditis are Staphylococcus aureus (Fig. 4) and Streptococci. From the Streptococci family commensal viridans and coagulase negative strains are most common, though other Streptococci are still seen along with Enterococci. Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, Kingella spp. (HACEK group) are also seen, but not as commonly [22]. The viridans Streptococci strains that cause infection are examples of bacteria that are already present in the patients mouth, but given the opportunity and the right conditions will cause infection. On the other hand Staphylococcus infection causing bacteria enter the blood stream through skin penetration via surgery, needles, catheters, etc. causing nosocomial infections. An example of bacteria that can cause infection from the gastrointestinal tract is Enterococcus.

Similarly, other organisms, when isolated, give doctors an idea of how infection took place [23]. For example, Pseudomonas spp (Fig 5) has been thought to originate through the contamination of street drugs with drinking water, as Pseudomonas is an organism that can survive very well in water. In children, P.aeruginosa can cause infective endocarditis by getting into the bloodstream by foot punctures and lacerations, common injuries in children. Along with Enterococcus, S. bovis and Clostridium septicum originate from the microbiota of the patient and may be signs of greater issues [24]. When these bacteria are found to be the cause of infections, colonoscopies are often immediately performed, as the passing of these otherwise commensal bacteria into the blood stream may be a sign that the barrier between the gut lumen and blood vessels that drain the intestines has been compromised (very serious). The previously mentioned HACEK group, are other bacteria that live in the mouth of patients and can end up on the needles of drug users via saliva (ironically in attempts to clean either the needle or the skin) or in patients with poor dental hygiene, as it has been discussed. Yeast such as Candida albicans have also been associated with microbes that cause infective endocarditis in intravenous drug users as well as immune compromised patients. Other fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum, Aspergillus, and Tricosporon asahii have also been known to cause infective endocarditis.

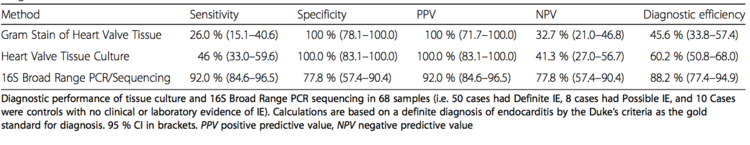

Identification of these microbes, mainly bacteria, is done by culturing blood samples of the patient [25]. Other techniques include the culturing of excised valve tissue, pleural fluid (fluid surrounding lungs), and sputum (another part of the endocardium). As well, cultures can be obtained from emboli, which are small pieces that fall from damaged valves due to vegetation. These emboli also prove problematic as they can cause blockages leading to hemorrhages. However, current research shows that PCR and/or sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA is extremely accurate and in general a better tool for bacterial identification. Figure 6 shows the results of efficiency and facility in identification of infective endocarditis causing bacteria using different techniques [26].

Treatment

Treatment is simple yet complex. If you have been diagnosed with infective endocarditis, you will need treatment by either high dose antibiotics, generally intravenously, or surgery in order to remove the vegetation and repair the valve (video provided, beware of graphic content: [27] ). Intravenous high dose antibiotics is generally used in order to kill all of the bacteria. As it was talked about earlier, because there is no direct blood supply to the affected areas, it is difficult for medicines to reach the problem. In the cases of acute or short incubation infective endocarditis, antibiotics are administered as soon as blood is drawn for bacterial identification, given the nature of infection [28]. In patients with subacute or long term incubation, antibiotic regiment can wait until identification can be confirmed via culturing. Different strains will need different antibiotics, so this is usually a good thing. As the most common cause of infective endocarditis, Staphylococcus aureus is resistant to penicillin and must be treated using oxacillin, and when resistant to that, the more potent vancomycin is used. For other cultures, the use of penicillin is sufficient, along with ceftriaxone and other aminoglycosides.

Conclusion

Though infective endocarditis can be a life threatening disease, it is treatable thanks to modern antibiotics and surgical procedures. The problem arises from the difficulty in diagnosis of the infection and identifying the causative agent, but research shows promise. Through gram staining, blood and tissue culturing and PCR/sequencing techniques, scientists and doctors have been able to further identify these causative agents, providing clues into social origins of endocarditis. For example, distinguishing between what part of the endocardium is affected and by what it is affected, doctors can determine if the infection originated due to dental procedure infections or intravenous drug usage. This helps doctors treat the underlying causes of endocarditis and help prevent future cases. As scientific research progresses, scientists are able to understand more about these bacteria and fungi helping treat and prevent infections such as those of infective endocarditis.

References

Links:

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/basics/causes/con-20022403

http://www.amjmed.com/article/0002-9343(94)90143-0/pdf

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/905502-overview

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/basics/treatment/con-20022403

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/basics/symptoms/con-20022403

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/basics/risk-factors/con-20022403

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Infective_endocarditis

http://www.webmd.com/oral-health/endocarditis-prevention

http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/endocarditis/basics/definition/con-20022403

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4828839/pdf/12879_2016_Article_1476.pdf

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lc0wlwzQGhA

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3625651/

http://www.bacteriainphotos.com/photo%20gallery/Pseudomonas%20spp..jpg

http://www.topteny.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/heart-7.jpg