The Gut-Brain Axis and OCD

Introduction

By Ali Hatfield

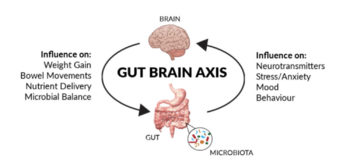

The systems of the human body are connected in many more ways than the average person could think of. At first thought the digestive system, commonly referred to as the human gut, is deeply separated from the nervous system. However, recent research has shown that this is not the case, and there are many more connections between the two than most would imagine. Studies have shown correlations between human gut microbial activity having an effect on psychological well-being, either improving or declining mental health. In cases with a direct connection between gut microbiota and brain activity, this is known as the gut-brain axis. This communication from bowel to brain is bidirectional, with interference in the gut microbiota having the ability to alter the nervous system, and interference with the nervous system having the ability to alter gut activity. [1]

The gut microbiota can affect a variety of psychological disorders, one of which being obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).[2] OCD is an anxiety related disorder that is believed to affect about 1% of the population, yet the number of diagnoses is hard to perfect in the case of psychological conditions.[3] It is reportedly more frequently found in women than in men in adults (age >18) and more frequently found in boys than girls (age <18).[3] Like many psychological disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder is a condition that displays a wide range of symptoms and manifests itself differently in each person afflicted by the disorder.

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

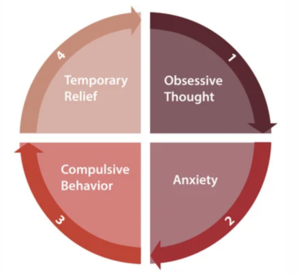

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder is categorized by intrusive thoughts or ideas, which are known as obsessions repeatedly occurring in a person’s mind, and often of a negative nature. These obsessions are then followed by the need to perform a type of compulsion to neutralize the feelings of anxiety these ideas spark.[4] The range in content and severity for both the obsessions and compulsions in OCD patients is extraordinarily broad, with some cases causing minor inconvenience while others can be debilitating. Common obsessions often relate to the idea of harm coming to a person with OCD or their loved ones, fear of contamination, embarrassment, or shame, or the need for things to be exact or in order. Compulsions are often a combination of mental acts, such as counting or repeating words, to physical acts, such as checking, cleaning, or rearranging.[4] Cases of OCD can also be considered either more focused specifically towards obsessions or compulsions separately. Some people with OCD may experience more of an issue with the intrusive thoughts or images but not feel as much of a need to complete compulsions to satisfy themselves, while others feel the compulsion to complete acts to neutralize anxiety that has not been generated by obsessive thoughts. Due to the nature of the disease, it is referred to as one of the most common serious mental illnesses.[4]

OCD onset usually occurs during adolescence, with most people who have it developing it before the age of 25.[6] Despite a higher prevalence of cases in women, onset has shown to occur earlier in men.[6] Comorbidities, in which multiple disorders are present in one person, are exceedingly common with OCD, and the afflictions of one or two other psychological conditions often heighten the symptoms of each other. The highest percentage of OCD cases that present with a comorbidity is with major depressive disorder, which accompanies OCD in approximately one third of patients.[7] Additional comorbidities often seen are generalized anxiety disorder, PTSD, eating disorders, social phobia, and other mood and anxiety disorders.[6]

Historically, the most successful treatment methods for OCD is a combination of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Due to many of its systematic and structural similarities to other anxiety disorders, and frequent comorbidities to depressive disorders, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are a common pharmaceutical treatment for OCD patients, and the combination with cognitive behavioral therapy has shown great management and symptom prevention capabilities.[5] These therapies only aim to target the neurological background of obsessive compulsive disorder by altering brain chemistry and providing exposure to specific fears and anxieties. While these have proven to be beneficial, anxiety disorders often have roots in other parts of the body that may be interesting to look at for therapeutic purposes.

The Gut-Brain Axis and OCD

Humans have developed a symbiotic relationship with the up to 40,000 species of bacteria that live in their digestive tract.[8] The presence of microbes in the digestive system is necessary for survival and a specific balance of organisms is required for proper functioning. At a normal state, Firmicutes and Bacteriodetes make up about 90% of the intestinal bacteria populations, but each individual has a unique gut microbiota.[10] Dysregulation of the gut microbiota has been closely correlated with anxiety disorders, one of which being OCD.[9] Two primary mechanisms that are hypothesized to cause or worsen OCD symptoms are the role of stress on the microbiome and the altering of the microbiome through antibiotics.

The HPA Axis

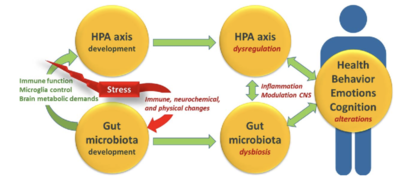

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, also known as the HPA axis, is a broader neural pathway that plays an important regulatory role in the brain’s immune and stress responses.[9] The HPA axis often is hyperactive in people with OCD, with an increased flux of the corticotropin releasing and adrenocorticotropic hormones that come from the HPA axis being elevated in OCD patients.[9] The HPA axis has recently been discovered to be affected by the composition of the gut microbiome, and this directly links to obsessive compulsive behaviors. Notably, the HPA axis is activated by Escherichia coli infection, as it triggers the immune response.[9] A severe enough immune response from the HPA axis to an infection from a gut bacterial infection can hyperactivate the HPA axis enough to trigger the brain regions that cause the obsessions and compulsions linked to OCD. The HPA axis is also a good example of the bidirectionality of the gut-brain axis. In addition to higher numbers of some bacteria, such as E. coli, instigating activity of the HPA axis, HPA axis activity can alter concentrations of some microbes in the gut. Following high exposure to stress that activates the HPA axis, the relative abundance of bacteria in the genus Clostridium rose while the relative abundance of the genus Bacteroides fell.[9][10] Another factor that supports the linkage of the HPA axis, microbiome, and OCD is the rapid onset of symptoms after high stress experiences that activate the HPA axis.[9] Events such as pregnancy, childbirth, social stressors, and physical stressors are all known to affect the HPA axis and have all led to microbial changes in the guts of animal models.[10] In humans there have also been reports of this stressor type precipitating the onset of OCD with a focus on pregnant women. Some hormones that circulate in a female’s body naturally stimulate the HPA axis, which then alters the gut microbiota, which relates to the higher prevalence of OCD found in pregnant women in comparison to other populations.[9]

Antibiotics

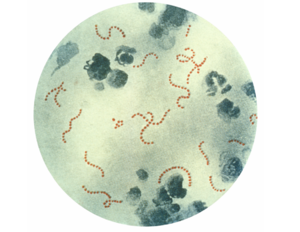

In a set of children who have had a prepubescent diagnosis with OCD, some cases have followed a child’s experience suffering from group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infections (GABHS) which caused the development of pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS).[9] Streptococcus pyogenes are the bacteria classified as group A, and they cause infections such as pharyngitis, or classic strep throat, as well as scarlet fever and acute rheumatic arthritis, among others.[11] To combat S. pyogenes, the most common treatment involves antibiotics being given to kill the infectious bacteria. Due to the incredibly extensive bacterial network of the human gut, taking antibiotics can wreak havoc on the microbiota. Many people who have to take antibiotics have experienced digestive issues, commonly diarrhea, and it is usually suggested to take antibiotics with food to prevent this. In early studies connecting OCD to GABHS and subsequent PANDAS, it was believed the bacteria itself may be causing the onset of OCD cases in affected children. With more knowledge on the gut-brain axis and connections between gut microbiota and psychological stability, it is now hypothesized that it is not S. pyogenes leading to OCD, but the antibiotics used in treatment reducing the concentration of other bacteria in the gut.[9] In recent years, the use of antibiotics has been a common topic of conversation in healthcare, as many believe that there is overprescription of antibiotics in cases where it is not necessary. While this is different from the kickback to other prescription drugs, such as addictive pain medications, it is is still a hot topic of interest due to the potential damage that can be done on the gut microbiota.

Digestive and Psychological Comorbidities

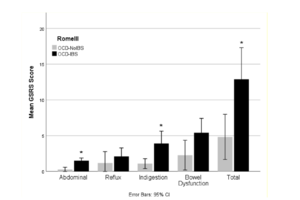

When thinking about comorbidities in a psychological context, people often think of the possibility of being comorbid with other psychiatric disorders. For example, it is known that OCD patients often have comorbidities of major depressive disorder, eating disorders, or other anxiety disorders. With the gut-brain axis in mind, however, a new perspective of physical comorbidities has been discovered. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common functional gastrointestinal disorder, categorized by stomach pain, bloating, and either constipation or diarrhea.[12] Despite how common IBS is, with around 10-15% of the population believed to have some form of it, the pathology of IBS is not fully understood and it is frequently thought of as a disorder of the gut-brain axis, sharing some kind of pathophysiological mechanism.[12][13] Similar to how OCD and other psychiatric conditions have diagnostic criteria found in the DSM-V, to be diagnosed with IBS patients have to meet Rome criteria. Cross sectional studies of populations that fit the criteria for both of these disorders have been done, confirming a definite correlation between the two issues that support the idea of a gut-brain connection in both.[14] One study found that in comparison to a control group of non-OCD patients, of which only 4.5% met Rome III criteria for IBS, 47.6% of OCD patients in the same study met criteria.[12] Apart from this, OCD afflicted people who did not meet the Rome criteria for IBS still reported experiencing digestive issues, just at a lower rate. While there has been no significant connection between specific OCD symptoms and the occurrence of comorbid IBS, there is a noted phenomenon called “bowel obsessional syndrome”. This condition strongly links the symptoms of OCD to themes surrounding digestion, creating irrational and overwhelming anxieties over things like fecal movements and bowel habits that lead to OCD-like compulsions to maintain control of bodily function.[12] With so many parallels in the mindset of people who experience this to those with OCD, bowel obsessional syndrome is often regarded as a subtype of OCD, and often is found in the high number of patients that have both OCD and IBS.[12]

Microbial Remediation of OCD

Probiotics

With evidence that OCD can derive from gut microbiota dysregulation, the next step is to figure out how to remediate the gut microbiota to reduce obsessive-compulsive symptoms in these patients. Probiotics are something frequently seen across supermarkets and health food stores as something that is good for health, often thrown on labels to entice people to buy a product. For gut microbiota dysregulation and its associated issues, this appears to actually be the case, with probiotics being used for therapeutic effects in patients with psychological disorders. While in use for major depression and some other mood disorders, it is not a common treatment yet for OCD specifically.[9] This is due to lack of testing and research on probiotics with OCD patients, but the belief is that probiotics could also help regulate the microbiota enough to treat OCD. The main idea of probiotics is the reintroduction of beneficial bacteria to the gut to help maintain homeostasis of the system.[9] For example, it has been found that administration of the bacteria Bifidobacterium infantis, a lactic acid bacteria found in the same group as Lactobacillus, increased levels of tryptophan which acts as a precursor for the neurotransmitter serotonin.[9] The direct tie between bacterial introduction and neurotransmitter concentration supports the conclusion that the gut-brain axis exists, and that the gut microbiota can have a significant role in psychological regulation. Another way that probiotics can change the course of psychological illness is the ability they have to reduce intestinal permeability, which can block the translocation of harmful bacteria to signal the HPA axis or other parts of the brain that cause OCD symptoms.[8] In terms of depression and anxiety, one study showed that taking probiotics once a day for close to a month resulted in improvement of multiple types of anxiety and increased regulation of negative moods.[8] The research and literature leading to these discoveries have coined a new term, psychobiotics, for these therapeutic probiotics.[1]

Case Study: A Probiotic Success Story

There has been an interesting case in which bacterial administration successfully reduced OCD symptoms in a 16 year old male. This patient was being seen for severe obsessive compulsive disorder and self-injurious behavior (SIB) that accompanied his diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder.[15] After a wide variety of failed pharmaceutical treatments to reduce his symptoms for both of these conditions, he began treatment ingesting the Saccharomyces boulardii species. S. boulardii is a nonpathogenic yeast that functions as both a prebiotic and probiotic and increases enzyme activity in the intestines.[15] It historically has been used as a treatment for gastrointestinal disorders and antibiotic associated diarrhea, especially in the cases of Clostridium difficile infection.[15] It helps regulate gut microbiota by preventing pathogenic adhesion and supporting growth of beneficial bacteria in the digestive tract.[15] At age 15, the patient began taking S. boulardii , and after a few months of adjusting and altering doses, results began to show. A previously homebound teenager, due to the extent of his OCD and SIB, was experiencing extreme symptom reduction. He no longer had to wear the helmet he wore to protect himself from self-injury, and the occurrence of SIB went from multiple times a day for about an hour at a time to once or twice a week for about 10 minutes at a time.[15] With the reduction in SIB came a reduction in the compulsions associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder, as well as some of the tics he experienced.[15] While this is both a rare and extreme case, it is something to keep in mind as researchers continue to search for psychiatric therapies. With how varied the human microbiota is and how connected it is to the nervous system, there is a high chance we can find more remedies similar to this case study.

Concerns and Considerations

With little concrete evidence on the use of probiotics for OCD treatment, concerns have been acknowledged in the hypotheses. Until the exact mechanism between the human gut bacterial population and nervous system that affects obsessive compulsive disorder is identified, introduction of just any probiotics will likely be ineffectual, and could possibly even be harmful to sufferers of OCD.[9] Primarily, while the restoration of a healthy concentration of gut bacteria is likely to have beneficial effects, if the homeostatic conditions are not maintained it can cause relapse.[9] To prevent this, a regular routine of probiotic administration would likely be necessary, which may defeat the purpose of using the microbiota as treatment if people are attempting it as an alternative to daily medication, such as SSRIs. Additionally, conditions that are impairing proper bacterial colonization in the gut must be remedied, and if the original issue in the gut is deriving from the central nervous system, this may create a negative cycle that prevents restoration of the gut microbiota.[9] Often, OCD sufferers have had their obsessions and compulsions for an extended period of time to the point that they have solidified in their regular lifestyle or routine. In cases such as these, improving microbial health in the gut to combat the biological basis of OCD might not be enough to alleviate the psychological symptoms.[9]

Conclusion

Research shows an undeniable connection between the human gut microbial community and the central nervous system, creating a bidirectional axis that affects each other regularly. Most well known is the correlation between gut health and depression and anxiety, but the correlations do not stop there. While there is less literature on the link between obsessive compulsive disorder and the gut-brain axis, enough is present to push the momentum forward on researching this topic. OCD is an illness that causes significant interference in the lives of those inflicted with it, and in order to treat it it needs to be fully understood. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and effect of antibiotics initially demonstrate this relationship, with the high overlap in OCD and IBS patients also supporting this. In short, gut microbiota dysregulation affects psychological well-being, with OCD being an example of the disorders it can cause or exacerbate. With this information, we can look into possible therapeutic interventions from the perspective of the gut microbiota, rather than just psychopharmacological options. Further research is needed to reach these steps, but as more is learned about the connection between gut and brain, massive scientific breakthroughs will follow.

References

[1] Osadchiy, V., Martin, C. R., & Mayer, E. A.. (2019). The Gut–Brain Axis and the Microbiome: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 17(2), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.002

[2] Rees, J., (2014) Obsessive–compulsive disorder and gut microbiota dysregulation. Medical Hypotheses, 82(2), 163-166.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.026

[3] Fireman, B., Koran, L. M., Leventhal, J. L., & Jacobson, A.. (2001). The Prevalence of Clinically Recognized Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in a Large Health Maintenance Organization. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1904–1910. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1904

[4] Heyman, I.. (2006). Obsessive-compulsive disorder. BMJ, 333(7565), 424–429. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.333.7565.424

[5] Franklin, M. E., Sapyta, J., Freeman, J. B., Khanna, M., Compton, S., Almirall, D., Moore, P., Choate-Summers, M., Garcia, A., Edson, A. L., Foa, E. B., & March, J. S.. (2011). Cognitive Behavior Therapy Augmentation of Pharmacotherapy in Pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. JAMA, 306(11), 1224. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1344

[6] Standford Medicine, About OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders. https://med.stanford.edu/ocd/about.html

[7] Pallanti, S., Grassi, G., Sarrecchia, E. D., Cantisani, A., & Pellegrini, M. (2011). Obsessive-compulsive disorder comorbidity: clinical assessment and therapeutic implications. Frontiers in psychiatry, 2, 70. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00070

[8] Lee, Y., & Kim, Y.-K.. (2021). Understanding the Connection Between the Gut–Brain Axis and Stress/Anxiety Disorders. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23(5). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-021-01235-x

[9] Rees, J., (2014) Obsessive–compulsive disorder and gut microbiota dysregulation. Medical Hypotheses, 82(2), 163-166.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.026

[10] Misiak, B., Łoniewski, I., Marlicz, W., Frydecka, D., Szulc, A., Rudzki, L., Samochowiec, J.. (2020) The HPA axis dysregulation in severe mental illness: Can we shift the blame to gut microbiota? Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.109951

[11] Group A Streptococcal(GAS) Disease for Clinicians. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/groupastrep/diseases-hcp/index.html

[12] Turna, J., Grosman Kaplan, K., Patterson, B., Bercik, P., Anglin, R., Soreni, N., & Van Ameringen, M.. (2019). Higher prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and greater gastrointestinal symptoms in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 118, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.08.004

[13] Irritable Bowel Syndrome. American College of Gastroenterology. https://gi.org/topics/irritable-bowel-syndrome/#:~:text=IBS%20is%20common%20%E2%80%93%2010%25%20to,the%20United%20States%20have%20it.

[14] Davarinejad, O., RostamiParsa, F., Radmehr, F., Farnia, V., & Alikhani, M. (2021). The prevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A cross-sectional study. Journal of education and health promotion, 10, 50. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_812_20

[15] Kobliner, V., Mumper, E., & Baker, S. M. (2018). Reduction in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and Self-Injurious Behavior With Saccharomyces boulardii in a Child with Autism: A Case Report. Integrative medicine (Encinitas, Calif.), 17(6), 38–41.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2022, Kenyon College