The Impact of the Skin Microbiome and Genetics on Eczema

Introduction

The skin is instrumental with regards to maintaining human health, as it is the first line of defense against pathogens. The manner in which skin is able to do this is through its diverse microbiome. One of the most common skin infections, affecting mainly children but also adults, is atopic dermatitis (AD), commonly known as eczema. The manner in which eczema typically manifests itself differs by skin tone and composition, but symptoms typically include the following: red and itchy patches and oozing that ranges in severity. As there is no cure, individuals with high severity AD have a compromised way of living, as studies suggest that being perceived with eczema can lead to symptoms of depression and anxiety, which can (in certain cases) prompt individuals to pursue an unhealthy lifestyle, worsening their AD symptoms and contributing to a negative cycle.[1] Thus, understanding how composition of the skin microbiome and genetic factors play their respective roles within the development of AD, can very much improve quality of life for many individuals.

Role of the Skin Microbiome in Development of Atopic Dermatitis

The skin microbiome consists of bacteria, such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, that serve a dual role within the microbiome. Usually, S. epidermidis aids in the synthesis of antimicrobial peptides, but upon disruption of the skin barrier, S. epidermidis takes on a more pathogenic-like behavior, causing certain diseases (like eczema) to increase in severity[2] When disruption of the skin barrier causes S. epidermidis to stop producing the antimicrobial peptides, it allows for further colonization of harmful bacteria on the skin. Disruption of the skin barrier can also elevate skin pH levels, which also favors the colonization of Staphylococcus aureus, a known instigator of skin infections. Staphylococcus aureus also can cause eczema to be more severe through its production of certain virulence factors, such as superantigens, which bind to antigen-presenting cells, which play an important role in the adaptive immune system, presenting antigens to T cells so that they can recognize them when the body encounters those antigens again.[3] This binding leads to the excessive stimulation of T cells, resulting in inflammation of the skin barrier. Ways in which Staphylococcus aureus can be combated include the application of topical calcineurin inhibitors, which are known to lower the inflammatory response present in patients with AD through the repression of cytokines, which is a protein that stimulates the immune system[4] However, not much has been done regarding the clinical applications of this treatment, so there is room for improvement.

Role of Genetic Predisposition in Development of Atopic Dermatitis

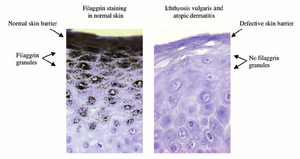

The presence of eczema can be linked to genetic predisposition, which refers to the probability that an individual develops a disease due to their genetics. Filaggrin is an important protein that plays an important role with respect to maintaining the stability and structure of the skin barrier. Thus, the lack of filaggrin severely compromises the function and structural integrity of the skin barrier. Filaggrin is regulated by the FLG gene. Loss-of-function (null) mutations, also known as null mutations associated with the FLG gene prevent filaggrin from being produced[5] Children of two parents with the null mutation of the FLG gene have an extreme genetic predisposition for the onset of eczema, which could be triggered later on in life by environmental factors. As filaggrin also has applications with respect to maintaining skin moisture levels, genetic predisposition to low skin moisture levels (caused by a mutation in the FLG gene) can be accelerated by extremely cold and dry environmental conditions, leading the skin barrier to become more susceptible to inflammation. In addition, a lack of the protein could be responsible for increased pathogenic entry into the skin barrier, further allowing for the triggering of skin conditions like AD.

Solutions (Modern Research) Involving AD

Eczema does not have a known cure, as the factors that play into the onset of the disease are very extensive, ranging from genetic predisposition from a mutation in the FLG gene, to environmental factors. However, ways to minimize the appearance of AD include topical calcineurin inhibitors, which were previously mentioned, and bleach baths. Bleach, formally known as sodium hypochlorite, has been experimentally demonstrated to have immense anti-bacterial properties, especially against Staphylococcus aureus. Surprisingly, the impact of bleach baths on epithelial cell health as well as pH is seemingly negligible, as some studies suggest[6] However, it is important to note that the long-term effects of bleach baths, including antibiotic resistance of S. aureus, has not been extensively studied, so those effects still remain unclear.

Conclusions and Future Prospects

As eczema is an atopic disorder, which means that it is the result of genetic predisposition to problems with the immune system, finding a cure or more effective methods to actually treat the root of the problem can aid with combating other similar conditions like asthma and nasal congestion. In addition, research relating to treatments that could target the source of atopic dermatitis in the first place, mutations with the FLG gene, could be beneficial.

References

- ↑ [ https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6947493/ Schonmann Y, Mansfield KE, Hayes JF, Abuabara K, Roberts A, Smeeth L, Langan SM. 2020. Atopic Eczema in Adulthood and Risk of Depression and Anxiety: A Population-Based Cohort Study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology in Practice. 8(1):248-257.e16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.030. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6947493/.]

- ↑ Brown MM, Horswill AR. 2020. Staphylococcus epidermidis—Skin Friend or foe? Kline KA, editor. PLOS Pathogens. 16(11):e1009026. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1009026. https://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1009026.

- ↑ Williams MR, Gallo RL. 2015. The Role of the Skin Microbiome in Atopic Dermatitis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 15(11). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-015-0567-4.

- ↑ George SM, Karanovic S, Harrison DA, Rani A, Birnie AJ, Bath-Hextall FJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. 2019 Oct 29. Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of eczema. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003871.pub3.

- ↑ George SM, Karanovic S, Harrison DA, Rani A, Birnie AJ, Bath-Hextall FJ, Ravenscroft JC, Williams HC. 2019 Oct 29. Interventions to reduce Staphylococcus aureus in the management of eczema. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003871.pub3.

- ↑ Chopra R, Vakharia PP, Sacotte R, Silverberg JI. 2017. Efficacy of bleach baths in reducing severity of atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. 119(5):435–440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2017.08.289.

Edited by [Natasha Jose], student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116, 2024, Kenyon College.