Biophysics of Cell Motility: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[Image:V22.gif|thumb|450px|right| von-Karmen vortex street motion. Image taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%A1rm%C3%A1n_vortex_street Wikipedia:Kármán vortex street]] | [[Image:V22.gif|thumb|450px|right| von-Karmen vortex street motion. Image taken from [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%A1rm%C3%A1n_vortex_street Wikipedia:Kármán vortex street]]] | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

Revision as of 20:22, 12 May 2011

Introduction

By: Dhruv Kumar Vig

Overview of Cell Motility

Cells are the primary building blocks of all living organisms and at a basic level their functions consist of growing, replicating, and dividing. In order for a cell to complete these functions, they must produce force; cells are able to produce this force by using their internal molecular motors (Wolgemuth 2011). For example, in our muscles, myosin binds to actin filaments, thereby exerting forces (Wolgemuth 2011). These types of forces can be modeled using Brownian motion; however, this kind of modeling fails to address the molecular binding energies that are used by these molecules (Wolgemuth 2011). For instance, the binding and hydrolysis of ATP to a molecule completes a cycle of rotation that generates force; therefore, these molecules can be viewed as motors which can then be described by their force velocity relationship. It is these forces that are generated mainly by bacterial rotary flagella, located either externally or internally, and eukaryotic whip-like flagella that allow cells to move by gliding, swimming, twitching, or crawling (Wolgemuth 2011).

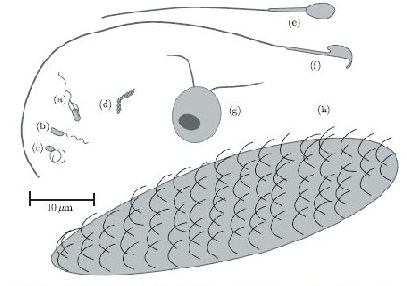

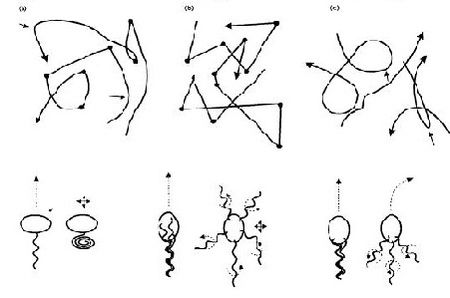

In terms of cell motility, an organism is defined as a “swimmer” if it moves by creating a periodic change in the shape of its body (Lauga and Powers 2008). Bacteria and Archaebacteria use ionic flux channels to drive their molecular motors that power the motion of their filamentary objects (Wolgemuth 2011). For example, E. coli use flagella that rotate counterclockwise and form bundles in order to push the bacteria forward (Armitage and Schmittt 1997) (Figure 1a). When the bacteria switch to counterclockwise rotation the bundles are broken apart and the cell tumbles (Figure 2b); after the bundles reform, the bacteria is facing a new direction in which it can move (Armitage and Schmitt 1997). Calobacter crescentus ’ filaments turn in a clockwise motion that pushes the bacterium forward, while counter-clockwise motion pulls the bacterium backward (Lauga and Powers 2008) (Figure 1b); Rhodobacter sphaeroides’ filaments only turn one direction (Lauga and Powers 2008) and periodically stop to re-orient itself (Armitage and Schmidt 1997) (Figure 1c and Figure 2a). In a similar manner, Sinorhizobium_meliloti , has several right-handed flagella that allow for quick forward swimming when the flagella form bundles and directional changes when the flagella rotate at different rates (Figure 2c) (Armitage and Schmidt 1997). Another example of bacteria with external flagella is spermatozoon which uses its flagella to produce a whip-like motion. This is possible because its molecular motors are present throughout its filament (Figure 1e and 1f) (Lauga and Powers 2008). Furthermore, some bacteria do not need external flagella to move; Spiroplasma ,for instance, swims by circulating the kinks that are throughout its body (Figure 1d) (Lauga and Powers 2008).

Spirochetes are a phylum of bacteria that contain internal flagella (Lauga and Powers 2008) that are located within its periplasmic space (Dombrowski et al. 2009). In these bacteria, the flagella extend from each end of the spirochete, thus wrapping around the entire body of the bacteria (Lauga and Powers 2008). This gives the bacteria either a helical or a flat wave shape depending on the species (Dombrowksi et al. 2009). Since flagella in Spirochetes rotate within the periplasmic space its flagella contain both skeletal and motile functions (Dombrowski et al. 2009). The internal flagella allow Spirochetes to quickly swim through viscous fluids that normally cause other species of bacteria to slow down; additionally, since their flagella are located internally, spirochetes are protected from extreme environmental conditions and from some antibiotics (Dombrowski et al. 2009).

In comparison, Eukaryotes, have larger flagella and cilia than bacteria (Lauga and Powers 2008) and these structures are powered by dynein motors that are located along the length of the filaments (Wolgemuth 2011). Additionally, some organisms, such as Chlamydomonas reinhardtii ,have multiple flagella, exhibiting both cilia and flagella beat patterns (Lauga and Powers 2008). Chlamydomonas’ two whip-like flagella switch between synchronous and asynchronous beat patterns. This causes the bacteria to suddenly reorient themselves from a normal linear swimming pattern and it is this switch that is observed to be a “run and tumble” movement (Polin et al. 2009)(Figure 1g) . Paramecium , on the other hand, uses the coordinated beat patterns of their cilia to move (Figure 1h).

New technological advances in the field of microscopy have led to an increase in the study and experimentation of cell motility. Brownian motion models are being replaced by more complex physical equations that have been derived to model avenues that range from bacterial turbulence, swarming dynamics and wound healing, to Lyme disease.

Technological Advances

Light-microscopy has normally been used to observe and track cells as they move. Now, however, fluorescent dyes can be used to stain a bacteria's flagella, thus illuminating the key cellular structures required for swimming (Lauga and Powers 2008). Furthermore, a technique known as “optical trapping” uses a laser beam to generate a change in momentum in cells that results in generation of force (Koning et al. 1996). This measurement of the change in force allows for the recording of the interactions between molecules that contain single motor proteins (Nabiev et al. 2008). Additionally,atomic force microscopy can directly measure the force generated by cilia (Lauga and Powers 2008).

Reynolds Number

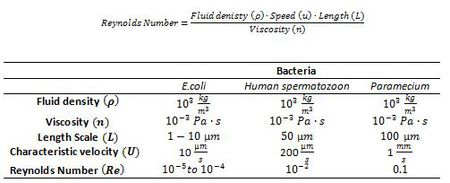

The world of microscopic organisms involves fluids that are highly viscous in nature and dominate any inertial forces that may be present (Happel and Brenner 1991). Given these conditions, the physics that governs the movements of these organisms at a microscopic level can be described by a low Reynolds Number (Lauga and Powers 2008). The Reynolds Number is a dimensionless quantity that is based on the Navier-Stokes Equation, which describes the motion of an incompressible Newtonian fluid. The Reynolds number is the ratio of inertia to viscosity of a fluid (Wolgemuth 2008) and it allows for a qualitative description of the flow regime from the Navier-Stokes equation (Lauga and Powers 2008) (Table 1). Since inertial forces are essentially zero at a low Reynolds number when bacterial motors stop turning the viscous fluid will provide more drag resistance on the bacteria causing the flagella to instantly stop moving. Furthermore, the force that bacteria require to swim in watery fluids will be less compared to more viscous solutions, since these solutions will be experiencing more drag. Therefore, based on this difference in forces, it becomes easy to distinguish between watery and viscous solutions.

Biophysical Studies

Swarming Dynamics

Bacterial swarming can contribute to the formation of biofilm communities which have been known to cause infections within the human body. For instance, these pathogenic bacteria have been found to form biofilms during transplant procedures. In particular, Proteus mirabilis has been known to swarm to form biofilms on urinary catheters resulting in blockages in the catheters, and thus pyelonephritis, septicemia and shock (Sharma and Anand 2002). Bacterial swarming can also produce virulent proteins that can cause kidney infections, wound infections, and possibly cystic fibrosis (Sharma and Anand 2002).

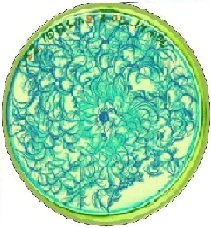

Zhang et al. (2009) studied the swarming motion of Paenibacillus dendritiformis colonies on semi-solid agar plates (Figure 6). The scientists were able to measure the speeds of each bacterium and the velocity fields that occur within the bacteria. This allowed them to observe the relationship between the bacteria’s average speed and the length and time scales of the jets that are characteristic of swarming motion (Zhang et al. 2009). Additionally, the scientists observed that, as the agar concentration increases the velocity of the bacteria decreases (Figure 7).

Applications of the Model

While Zhang's et al. (2009) model illustrated the movement of swarming bacteria on agar, their model followed the belief that at microscopic levels, viscous solutions will overwhelm any inertia forces, thus resulting in a low Reynolds number(Wikipedia: Stokes Flow). There are other factors beyond this concept of Stokes Flow that need to be considered; for instance, the occurrence of collisions between bacteria when they are found swimming highly dense populations. These types of collisions are identified as "bacterial turbulence" and require a more complex model to accurately reproduce their behavior.

Bacterial Turbulence

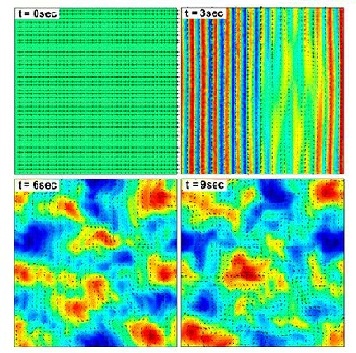

It is suspected that as the concentration of bacteria increases there should be a decrease in the Reynolds number. Since increasing the concentration of bacteria, increases the fluid flow between neighboring bacteria, this will cause the neighboring bacteria to feel drag due to the velocity difference between each bacterium (Wolgemuth 2008). However, bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis , show an increase in Reynolds number when found in dense colonies (Wolgemuth 2008). In these areas, a jet-like fluid motion is observed that has speeds faster than the speed of each bacterium; these jet-like motions are similar to fluid dynamics known as von Karman vortex street, in which the Reynolds number is greater than fifty (Wolgemuth 2008). These swimming patterns, which have high Reynolds numbers for their fluid dynamics, are known as “bacterial turbulence” (Wolgemuth 2008).

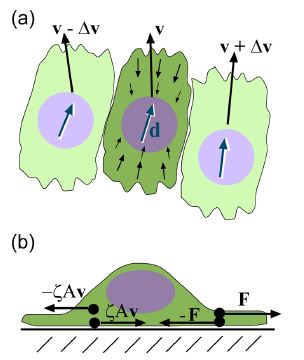

Wolgemuth (2008) developed a two-phase model that analyzed the group swimming dynamics of dense colonies of bacteria i.e. “bacterial turbulence.” Wolgemuth’s model treats the fluid and bacteria independently, and is based off of rod-like bacteria, like Bacillus subtilis , in which entropic forces will favor the restricted alignment of the bacteria (Wolgemuth 2008) (Figure 3). Wolgemuth (2008) defined a series of equations and parameters that make up his two-phase group swimming model; these parameters reproduce the behavior that is observed in regions where “bacterial turbulence” is present (Figure 4 and 5).

Applications of the Model

Modeling the behavior associated with “bacterial turbulence” has several medical and industrial applications. Large concentrations of bacteria are found in filtration systems, like dead-end filtration, in which water containing bacteria are forced through a micro-filter (Wolgemuth 2008). Additionally, biofilms can also be produced by the aggregation of bacteria, thus resulting in corrosion and infections (Wolgeumuth 2008).

Wound Healing

Epithelial cells have been observed to crawl in order to heal a wound; this crawling is powered by the cell’s actin cytoskeleton (Lee and Wolgemuth 2011). The general process can be broken into three steps. The first requires the polymerization of actin located in the front of the cell. Second, the organism needs to obtain some kind of grip to its surrounding environment. Third, enough force needs to be generated to move the rest of the cell forward (Wolgemuth 2011). Lee and Wolgemuth (2011) studied the possibility that the cellular movement that occurs during wound healing is a mechanical process that is based on cells crawling and not powered by myosin or other biochemical proteins. The scientists developed a model to incorporate the characteristics of single migrating cells and cell-cell adhesions. Their model illustrated that the cells are aligned along a set direction and velocity, and a difference in velocity between neighboring cells can cause viscous stress that produces torque and therefore causes rotational movement between the neighboring cells (Figure 7a). Additionally, based on Newton’s third law of motion, they assumed that a cell which exerts a force on a substrate will experience an equal and opposite force exerted onto it from the substrate. This causes the cell to generate a thrust force that is counteracted by a drag force exerted by the substrate. The result is the production of dipole stress in the cell (Figure 7b).

Lee and Wolgemuth (2011) applied their model to examine the healing process in a one-dimensional wound. In these wounds, a straight cut is made through the layer of cells and the rate at which the cells fill this area was measured. The dipole stress in this case caused pressure to exert a compressive force into the wounded area; this caused an expansive pressure to be exerted back onto the cell strip. It is this pressure that causes cells to spread over the wounded area (Figure 8) (Lee and Wolgemuth 2011).

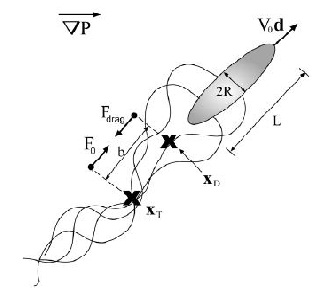

Lyme Disease

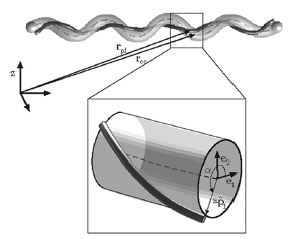

Borrelia burgdorferi , the spirochete responsible for Lyme disease, is transmitted through ticks in which with it has a mutualistic relationship. The ticks obtain the bacteria when they bite mice or deer that are infected with Lyme disease. The disease is then transmitted to humans through a bite from an infected tick PubMed: Lyme disease (Diagram 1). Studies with Borrelia burgdorferi have discovered a relationship between the bacteria’s motility and its virulence (Dombrowski et al. 2009). These spirochetes have flat-wave morphologies, and it has been found that these bacteria are able to swim due to the thrust generated by the deformation of its cell wall that it caused by the rotation of its periplasmic flagella (Dombrowski et al. 2009) (Figure 9). This deformation of the cell wall generates a force back that causes the periplasmic flagella to also deform (Dombrowski et al. 2009). In order to test whether this qualitative mechanism is sufficient to cause the flat-wave morphology observed in Borrelia burgdorferi , Dombrowski et al. (2009) developed a mathematical model in which they characterized the periplasmic flagella and cell wall of the bacteria as elastic objects (Figure 10).

Model of Borrelia burgdorderi

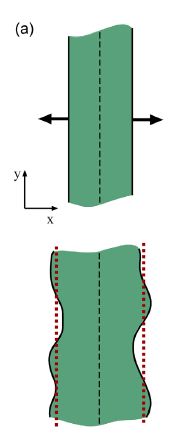

Dombrowski et al. (2009) assumed that the flagella of the bacteria are contained to a single position on the outer perimeter of the bacteria’s cell wall, and that the flagella are free to slide. The scientists found that if the bacteria's cell wall is more rigid than its flagella, the bacteria will be almost straight with its flagella wrapping around the cell wall. Furthermore, increasing the bacteria’s ratio of twisting to bending causes the cell wall to deform into the flat-wave morphology that is normally observed in Borrelia burgdorferi (Figure 10a and d) (Dombrowski et al. 2009). Additionally, the model predicted that, in this flat-wave morphology, the periplasmic flagella will wrap around the cell wall in the direction opposite in which it is located (Dombrowski et al. 2009). When the bacteria’s ratio of twisting to bending is equal to 1.0 the amplitude of the bacteria increases slightly, but its wavelength decreases. When this occurs, flat-wave morphology is not observed; instead, the shape of the cell becomes a flattened helical form (Figure 10c) (Dombrowski et al. 2009). Finally, the scientists observed that increasing the cell’s radius led the cell to morph from a more helical shape to a more flattened one(Figure 10e). Overall, the scientist’s model illustrated that the flat-wave morphology observed in Borrelia burgdorferi is indeed created by the coupling of the helical periplasmic flagella to the cell wall.

Applications of the Model

The model of the mechanical interactions between the perisplamic flagella and cell wall in Borrelia burgdorferi provides a foundation for understanding the movement of similar species of spirochetes. One such example is the spirochete, Treponema pallidum , which causes Syphilis in humans. Additionally, while Dombrowski's et al. (2009) model focuses on the filaments that make up spirochetes, their model successfully described the physics involved in general elastic filaments. Therefore, their findings can be applied to other biological structures that are also composed of organized filaments. For example, α-helix proteins are interlinked with each other to from helix bundles that form coiled-coil protein motifs that play a role in HIV infections (Wikipedia: Role of coiled-coil in HIV). Another example, on a molecular scale is the muscle protein,F-actin, which is also composed of several strands of filaments that aid in muscle contraction (Dombrowski et al. 2009). Finally, on a more cellular level, cylindrical micro-tubules make up the major component of eurkaryotic flagella and cilia, known as an axoneme, which allows for the flexibility of the filaments (Dombrowski et al. 2009).

Future Directions

Bioengineering artificial swimmers

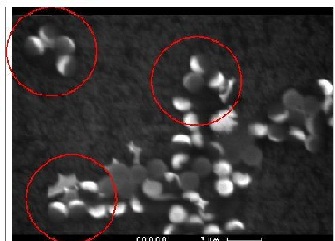

Bioengineering has led to the proposal and development of artificial swimming devices that can move at low Reynolds numbers. These devices can be divided into three separate categories. The first and second group are swimmers that move by deformation of their cell wall; however, they differ because the the first group can orientate themselves in a limited manner, while the second group can take on any form necessary to achieve movement. The third uses chemical reactions to power their locomotion. The chemical reaction leads to an imbalance in osmotic pressure on the body of the organism, which leads to propulsion of the organism i.e. movement (Lauga and Powers 2008). An example, of an artificial swimmer from the third category is placing polystyrene balls in a hydrogen peroxide solution and coating them with platinum. Experiments have indicated that these polystyrene balls move with the same velocity as bacteria; thus, they could possibly be used to deliver drugs throughout the human body. [2] (Figure 11.)

Manipulating low Reynolds Numbers

Scientists have also been experimenting with the advantages that can be obtained from solutions that have low Reynolds numbers. Experiments have shown that despite the highly viscous solutions at microscopic levels, swimming bacteria can still perform "cargo-towing"; that is attaching bacteria to solid objects in order to move the objects through the solutions (Lauga and Powers 2008). This concept could be extended to medicine in which a drug is transported through the blood stream, a highly viscous solution, to its target sites. Furthermore, other experiments have revealed that bacteria swimming in fluids with low Reynolds numbers will generate kinetic energy, causing the temperature in the solutions to increase (Lauga and Powers 2008).

Optimization of Cell Motility

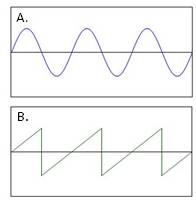

Experiments are also underway that are optimizing a cell's movement at low Reynolds number. For example, previous studies have shown that flagella are helical filaments that produce sinusoidal waves (Figure 12a) and optimization studies have been able to show that flagella produce these waves at an angle(θ) = 45o. Furthermore, when a bacteria increases its velocity, its flagella will in turn produce quicker rotations, thus increasing the frequency of the sine waves. Optimization studies have now been able to show that when this phenomenon occurs, the flagella lose their sinusoid wave characteristics and instead generate a sawtooth wave (Figure 12b) with an optimal angle(θ) = 40o. Thus, optimization studies are useful to measure how the physical characteristics of a bacterium can change at varying conditions (Lauga and Powers 2008).

Conclusions

Recent technological advances have led to an increase in communication between biologists and physicists and this collaboration has led to a more quantitative understanding in the field of biology. Physicists have been able to develop equations and parameters for basic cellular function that allows for the computation of molecular interactions that normally cannot be observed in an experimental center (Wolgemuth 2011). Specifically, in the of field cell motility, physicists have been able to create theoretical models that recreate the movement of bacterial cells. These models range from a bacteria swarming over an agar plate to evaluating the elastic nature of bacterial filaments and the role it plays in Lyme Disease. Overall, the greatest advantage of creating these theoretical models is that they can continually be applied to an endless number of scenarios in the field of biology.

References

Happel,J. and Brenner, Howard. “Low Reynolds number hydrodynamics.” Springer . 1991. p. 42

Wolgemuth, C.W. “Does cell biology need physicists?” Physics .2011. Volume 4, issue 4, p. 1-7