Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSGs) of Trypanosomes: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Curated}} | |||

==Trypanosomes== | ==Trypanosomes== | ||

[[Image: T.brucei_SEM.jpg|thumb|600px|right|Figure 1. Colorized SEM of <I>T. brucei</I>, and erythrocytes [ | [[Image: T.brucei_SEM.jpg|thumb|600px|right|Figure 1. Colorized SEM of <I>T. brucei</I>, and erythrocytes [1].]] | ||

<br>By Kelly Wahl<br> | <br>By Kelly Wahl<br> | ||

The trypanosomes shown in Figure 1 are single-celled, flagellated, eukaryotic parasites responsible for African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease. The African tsetse fly (subgenus <I>Glossina morsitans</I>) as seen in Figure 2, transmits the strains <I>Trypanosoma brucei gambiense</I> and <I>Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense</I> through its bite [2]. In central and South America the kissing bug (subfamily <I>Triatominae</I>) as shown in Figure 3, spreads <I>Trypanosoma cruzi</I> through its feces. People become infected when feces enter the body through mucosal membranes, or broken skin (bite marks or scratches). Vertical transmission from mother to child, and infection via infected blood or organs are also routes of transmission but they are very rare. There are many other species of trypanosomes but only <I>T. brucei</I>, and <I>T. cruzi</I> are relevant to humans [3]. | |||

[[Image: Tsetsefly.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Figure 2. Tsetse fly with a blood meal, vector of <I>T. brucei</I> [5].]] | |||

[[Image: Kissingbug.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Figure 3. Kissing bug, arthropod vector of <I>T. cruzi</I> [6].]] | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

These parasites are part of the order Kinetoplastidia, which broke off from the common eukaryotic ancestor fairly early on. Kinetoplastids are named after the kinetoplast at the base of their flagellum. A kinetoplast is a mitochondrion with coiled mitochondrial and genomic DNA. The kinetoplast changes size and shape throughout the parasite’s life cycle and is the target site of the anti-parasitic drug ethidium [3,4]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Trypanosome Infection; Sleeping Sickness, and Chagas Disease== | ==Trypanosome Infection; Sleeping Sickness, and Chagas Disease== | ||

<b>Sleeping Sickness</b> | <b>Sleeping Sickness</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

After a person is bitten they may develop a sore called a chancre and have headaches, fevers, muscle pain, joint pain, enlarged, tender lymph nodes (Winterbottom’s sign) and possibly a rash that last for about two weeks. During this first stage of infection known as the haemolymphatic stage, parasites are actively multiply by binary fission in the blood and lymph circulatory systems. Both <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> and <I>T. b. gambiense</I> show the same clinical symptoms but symptoms are much milder in <I>T. b. gambiense</I> infections and usually last for a longer period of time [2,7]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

The second stage of infection is neurological. | The second stage of infection is neurological. Parasites have crossed the blood-brain barrier and are now multiplying in the central nervous system. classic symptoms include rapid weight loss, impaired motor skills, seizures, confusion, and changes in personality, coma, and death. A disrupted circadian rhythm is the source of this disease’s name. Patients lie awake at night but sleep during the day. Without treatment <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> infections can progress so rapidly that malnutrition, heart failure, or pneumonia kill the patient before neurological symptoms ever manifest. In <I>T. b. gambiense</I> infections disease progression is much slower and it can take years for a person to show any neurological symptoms [2]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<b>Chagas Disease</b> | <b>Chagas Disease</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Chagas disease is similar to sleeping sickness in many ways. There is an acute stage | Chagas disease is similar to sleeping sickness in many ways. There is an acute stage and a chronic stage. One of the classic signs of acute Chagas infection is Romana’s sign, the swelling of the area around the eye where the conjunctiva (mucosal tissue around the eye) or a site near the eye was the point of infection. Patients may not present with signs of infection such as a fever as <I>T. cruzi</I> parasites are multiplying in the bloodstream. Serious symptoms are rare in this stage of infection but can include; heart failure, chest pain, seizures, or paralysis [8]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Unlike sleeping sickness, Chagas disease only progresses to the chronic form | Unlike sleeping sickness, Chagas disease only progresses to the chronic form in 20 to 30% or people infected. The remaining 70 to 80% of people infected remain asymptomatic for life and may be unaware they are infected. As the parasite replicates in cardiac muscle and digestive smooth muscle patients develop cardiac problems such as irregular heartbeat, blood flow disorders, issues with heart muscle function, and blood clots as well as ulcers in the digestive tract [8]. Without treatment most chronic cases of Chagas disease are fatal [7]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<b>Treatment</b> | <b>Treatment</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Symptomatic trypanosome infection is usually fatal if left untreated. | Symptomatic trypanosome infection is usually fatal if left untreated. There are no vaccines or prophylactic drugs to prevent infection but there are treatments available for both stages of the disease. The earlier the diagnosis, the easier it is to manage symptoms with less toxic drugs that can kill the parasite before it reaches the central nervous system. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Why Are Trypanosomes | ==Why Are Trypanosomes an Economic and Public Health Concern== | ||

African trypanosomes not only affects people but also livestock animals like cows, camels, horses, donkey. In animals the disease is called <I>Nagana</I>. In endemic areas in sub-Saharan Africa where human and animal trypanosome infections are common farmers are unable to raise cattle further contributing to malnutrition in the area. Animals can also serve as reservoirs for <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> making it impossible to eradicate the endemic trypanosomiasis in humans if there are also infected cattle nearby. The behavior of the Tsetse fly vector also affects the distribution of those who are stricken by the disease. Those who rely on farming, fishing, and hunting are most at risk to be bitten by an infected tsetse fly and are also commonly the breadwinners in poor, rural populations [7]. There are estimated to be more than 70,000 cases annually in sub-Saharan Africa, which encompasses the entire geographic range of the Tsetse fly [2,3,7,9]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

African | African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease are part of a broader group of neglected tropical diseases that have no available vaccines and the drugs used to treat these diseases either have documented drug resistance against them or are very toxic. This group of neglected diseases is projected to account for 534,000 deaths a year and millions of years of functional life lost due to disability from disease. Developing countries bore the brunt of this burden, as the human and animal tolls of these diseases stunt economic development in affected areas [10]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Domestically, Chagas is a potential risk for blood and organ transplant recipients. It is estimated that more than 300,000 people living in the U.S. are infected with <I>T. cruzi</I>. Most infections were picked up from countries in the Americas where the disease is endemic but, there may be cases of natural transmission in North America because of the presence of triatome species [8]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

In this increasingly globalized world diseases that once hid in the jungles of South America and the plains of sub-Saharan Africa have ended up in the foyer of industrialized nations. Although trypanosomiasis is still considered a third-world disease, infections are continually being diagnosed in the first world and represent a risk to anyone that can get on a plane and travel to an affected area [2,7,8]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Transmission and Life Cycle== | ==Transmission and Life Cycle== | ||

[[Image: Lifecycyle_t.brucei.JPG|thumb|800px|right|Figure 4. Life cycle of <I>T. brucei</I> [ | [[Image: Lifecycyle_t.brucei.JPG|thumb|800px|right|Figure 4. Life cycle of <I>T. brucei</I> [2].]] | ||

<b>Life cycle</b> | <b>Life cycle</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

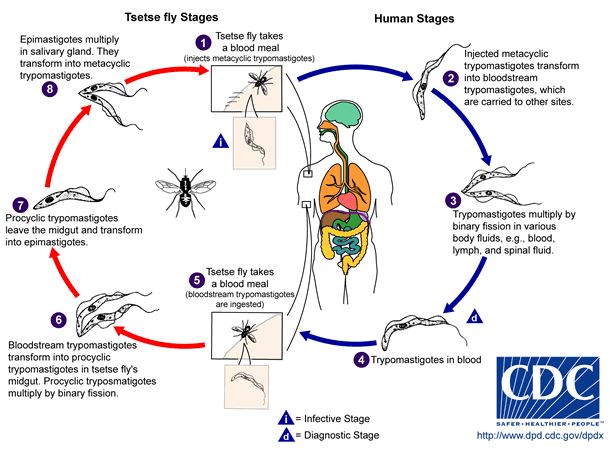

Trypanosomes cycle through five different morphological stages during their movement between arthropod vector and mammalian host [11].The morphology of trypomastigotes within the mammalian body are distinctly different from the trypomastigotes found in insects vectors because of their different metabolic needs and the presence or absence of variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs). In the midgut of the tsetse fly, after the ingestion of an infected blood meal procyclic trypomastigotes proliferate and move to the salivary gland where they differentiate into epimastigotes. The epimastigotes become VSG positive metacyclic epimastigotes. When the Tsetse fly bites a new mammalian host the metacyclic epimastigotes differentiate into a “slender” form and travel through the lymph and blood systems reproducing by binary fission in almost all organs of the body. Some of these dividing slender forms become “stumpy” and stop dividing. Although the stumpy form is no longer dividing within the mammalian host this form can survive in the fly midgut where it differentiates into the procyclic form again and completes the cycle of infection. When the parasites are in the mammalian host, numbers stages 1 through 5 in Figure 4, they are VSG positive and when they are in the Tsetse fly vector they are VSG negative [11, 3]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

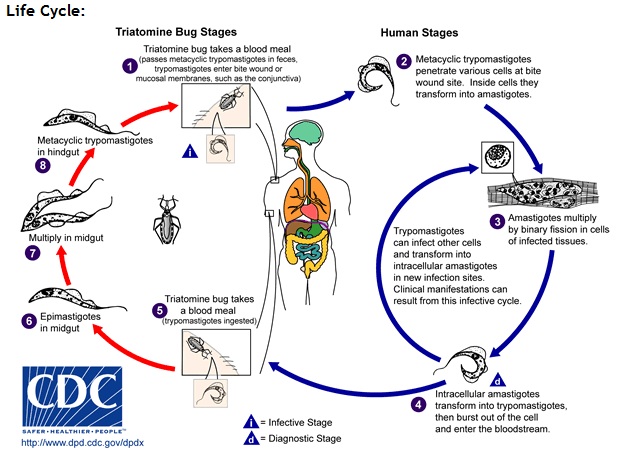

While <I>T. brucei</I> multiplies in the extracellular space between cells, <I>T. cruzi</I> does not have VSGs and hides from the immune system by living within host cells. <I>T. cruzi</I> is taken up by phagocytosis and escapes from the lysozyme into the cytoplasm with the help of a special protein that is activated at low pH [3]. Stage 3 in Figure 5 shows parasites dividing intracellularly in infected muscle cells [8]. | |||

[[Image: T.cruzi_lifecycle.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure 5. Life cycle of <I>T. cruzi</I> [8]]] | |||

While <I>T. brucei</I> multiplies in the extracellular space between cells, <I>T. cruzi</I> | |||

[[Image: T.cruzi_lifecycle.jpg|thumb|800px|center|Figure 5. Life cycle of <I>T. cruzi</I> [ | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSGs)== | ==Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSGs)== | ||

<b>VSGs</b> | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

VSGs allow trypanosomes to remain undetected by the adaptive immune system almost indefinitely and escape the complement system. Ten million identical VSGs form homodimers with one another and cover the parasite’s cell membrane like a dense homogenous forest. Although amino acid sequences and attached sugars vary from one VSG variant to another their secondary and tertiary structures are highly conserved. Only one VSG variant is expressed at a time. There are at least 200 active VSG alleles and more than 1000 silent alleles and psuedogenes also encoding VSG variants. Active genes can recombine with silent genes to form new unique active genes. This antigenetic switching allows trypomastigotes to continually change their “appearance” to the immune system and remain undetected through the course of infection [12]. This monotypic surface coat is eventually recognized by the immune system but by the time the body is ready to react the parasite has already silenced expression of that particular VSG and begun expressing a new VSG [13]. The expression of only a single VSG also makes it difficult for complement proteins to bind and help the innate immune system catch the parasite [14]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

The host immune response continually selects for the expression of new VSG variants. It is a case of the Red Queen’s race only <I>T. brucei</I> eventually wins as the host’s resources burn out and increasingly virulent variants are selected. There are more VSG variants than the immune system could ever recognize. VSGs can also actively modulate various components of the immune system to further avoid detection [11,12,13,14]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<b>VSG expression</b> | <b>VSG expression</b> | ||

[[Image: VSGexpression.jpg|thumb|800px|right|Figure 6. Two mechanisms for | [[Image: VSGexpression.jpg|thumb|800px|right|Figure 6. Two mechanisms for mono-telomeric expression of variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs)[12].]] | ||

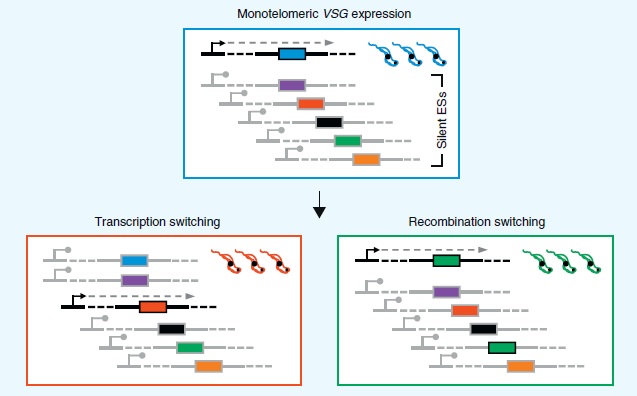

Only one of the 10-20 VSG telomeric sites expression sites is actively transcribed while the rest are silenced. Oddly enough these expression sites are transcribed by RNA polymerase I. <I>T. brucei</I> and other strains associated with Nangana or African sleeping sickness are the only eukaryotes that transcribe anything other than ribosomal RNA [12]. All other eukaryotes including <I>T. cruzi</I> only used RNA Pol I to transcribe ribosomal RNA [9]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

VSGs can be mono-telomerically expressed in one of two ways. The lower left panel of Figure 6 shows transcription switching. An actively transcribed telomeric site is silenced and another telomeric site begins active transcription. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Recombination switching as shown in the lower right panel of Figure 6, is the other way <I>T. brucei</I> switches VSG expression [12]. One of the thousand or so silent pseudogenes recombines with an active telomeric site so it can be expressed. This type of switching greatly increases the number of possible variants. The exact proteins involved and the mechanism by which they are able to recombine is still under study but there are a number of homologs involved in homologous recombination and DNA repair that are common to trypanosomes and other eukaryotes such as yeast [12,15]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

The | The coiling and uncoiling of chromatin determines which expression site is open for transcription while the rest are silenced. The nucleosomes, or spooling proteins that help structurally organize DNA are important for VSG expression. Expression of certain VSGs are repressed when these proteins twist DNA up in such a way that RNA polymerase cannot get to the promoter region to bind the expression site and begin transcription [12,15]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Expression site silencing requires at least six protein factors and operates by | Expression site silencing requires at least six protein factors and operates by a long or short-range mechanism. In short-range silencing, acetyl groups are removed from histones within 5 KBP of the expression site by histone deacetylase SIR2rp1. The histone acetylase HAT1 reverses silencing by adding acetyl groups to histones so they bind DNA less tightly and active transcription can take place. Long-range silencing is controlled about 50 kbp upstream of the expression site most likely through chromatin remodeling with a combination of histone deacetylases, acetylases, methylases, and other enzymes.The default state for VSG expression, is silence [12]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Current Research== | ==Current Research== | ||

<I>T. brucei</I>’s use of ever-changing VSGs is simple and elegant but there some confounding details in the expression and alternate function of VSGs that still need to be explored. One issue is the transition from one VSG surface coat to the next. What happens as a new coat is forming and the old coat is shedding from the cell surface? There is also the question of what other tricks trypanosomes have to avoid detection by the immune system besides their VSG coats [13,10]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<b>Expression of a Mosaic VSG Coat to Escape Early Detection by B-cells</b> | <b>Expression of a Mosaic VSG Coat to Escape Early Detection by B-cells</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Although only one VSG gene is expressed at a time the surface coat isn’t always | Although only one VSG gene is expressed at a time, the surface coat isn’t always monotypic. Even though a new gene is being expressed the existing VSG coat doesn’t just disappear overnight because it takes time to transcribe, translate, and transport the new VSGs to the surface and destroy residual mRNA and protein from the previous coat. It takes about 48 hours for the VSG coat to completely switch from one variant to another [13]. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[[Image: VSG_coexpression_on_cell_surface.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Figure 7. Fluorescence micrograph of trypanosome co-expressing LouTat1 VSG (wild-type)panel A and 117 VSG (transformed) panel B. Panel C represent an overlay of panels A and B | [[Image: VSG_coexpression_on_cell_surface.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Figure 7. Fluorescence micrograph of trypanosome co-expressing LouTat1 VSG (wild-type)panel A and 117 VSG (transformed) panel B. Panel C represent an overlay of panels A and B. Panel D shows the parasite without florescence [13].]] | ||

Dubois et al. (2005) found the 48 hour transition period where more than one VSG variant is present on the cell surface actually prevents B-cells from recognizing either the old or new VSGs. It’s like the trypomastigote call a timeout from the B-cell response while it’s changing clothes [13]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

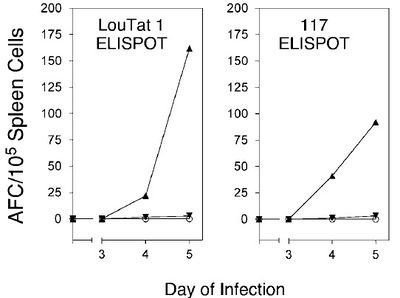

[[Image: B-cell_response.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Figure 8. B cell response in athymic mice after inoculation with wildtype and transformed <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> strain. Upward pointing triangles represent the wildtype strain expressing a single VSG, downward pointing triangles show transformed strain expressing both LouTat1 and 117 VSGs, the open circles are uninfected control mice. The X-axis shows days into the infection and the Y-axis | [[Image: B-cell_response.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Figure 8. B cell response in athymic mice after inoculation with wildtype and transformed <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> strain. Upward pointing triangles represent the wildtype strain expressing a single VSG, downward pointing triangles show transformed strain expressing both LouTat1 and 117 VSGs, the open circles are uninfected control mice. The X-axis shows days into the infection and the Y-axis is the number of activated B cells found in the spleen [13].]] | ||

To prove this, athymic mice (lacking T-cells) were infected with a strain of <I>T. b. rhodesiense</I> that had been transformed to express two VSGs at the same time. Panel A of Figure 7 shows fluorescence labeled LouTat1 VSG while panel B shows labeled 117 VSG. Panel C is an overlay of panels A and B. Wild-type trypanosomes could not be used because only a few parasites in a given population are switching coats at any one time and have mixed VSG coats. An ELISPOT assay measured the number of activated splenic B-cells producing antibodies. Figure 8 shows almost no B-cell activity in mice infected with trypanosomes co-expressing VSG 117 and LouTat1. One explanation is that B-cells are fooled by the insertion of variant VSGs in a monotypic coat during switching because the new VSGs breakup the pattern of identical epitopes required for the direct activation of B-cells void of any interactions with T-cells [13]. | |||

Wild-type trypanosomes could not be used because | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

<b>Trypanosomes Effects on Immune Function</b> | <b>Trypanosomes Effects on Immune Function</b> | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Besides hiding from the immune system with an ever-changing VSG surface coat trypanosomes also manage to down-regulate the function of various components of the immune system. one example | Besides hiding from the immune system with an ever-changing VSG surface coat, trypanosomes also manage to down-regulate the function of various components of the immune system. one example is the decreased ability of white blood cells to process and present newly encountered antigens after trypanosome infection [16]. | ||

<br><br> | |||

[[Image: IL-2level.jpg|thumb|400px|center|Figure 9. Relative ability of T-cell hybridomas to present novel antigens after trypanosome infection [16].]] | |||

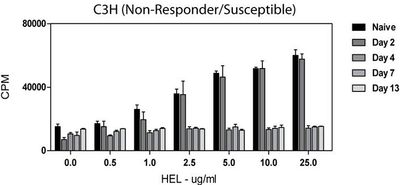

In 2009, Dagenais et al. showed white blood cells from infected mice displayed a decreased ability to respond to newly encountered hen egg lysozyme (HEL) antigen <I>ex vivo</I>. Extracted T-cells were irradiated and combined with immortal cells to form hybridomas that could be grown in cell culture. The ability to process and present an antigen was measured by the amount of interlukin-2 (IL-2) produced. IL-2 was used as a measure of immune function because it is an important cytokine that helps stimulate cytoxic T-cells and affects the development of T-cell memory, among other functions. To measure IL-2, radiolabeled thymidine was added to the hybridoma medium and the amount of IL-2 produced with incorporated radiolabeled thymidine was measured with a scintillation counter. A scintillation counter measures the amount of radiation in a sample as counts (or decays) per minute (CPM) [16]. | |||

<br><br> | |||

Naïve (uninfected) cells displayed a normal dose-dependent response to the introduction of HEL. As cells were exposed to more antigen, more IL-2 was produced. Figure 9 shows constant IL-2 production in cells from infected animals regardless of the concentration of HEL or length of time the animal had been infected before T-cells were harvested [16]. | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

==Conclusion== | |||

A better understanding of the interactions between <I>T. brucei</I> and immune could lead to the discovery of new anti-trypanosome drugs. Current drugs available for treatment are extremely toxic with side effects that can be almost as bad as trypanosomiasis itself [10]. New anti-parasite drugs could make a huge impact on areas where sleeping sickness and Nangana are endemic. Taking control of trypanosome diseases would be a huge win for international public health and give affected areas an economic boost from increased human productivity and the ability to raise livestock [3]. | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

[1] Parasite Museum (2009, June 4). <I>Trypanosoma brucei</I>. Retrieved April 25, 2011, from Parasite Museum: http://www.parasitemuseum.com/trypanosome/ | |||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010, November 2). <I>Parasites - African Trypanosomiasis (also known as Sleeping Sickness) </I>. Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sleepingsickness/ | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [3] Hunt, R. C. (2010, February 15). Parasitology-Chapter Three; Molecular Parasitology: Trypanosomes <I>Eukaryotic cells with a different way of doing things</I>. Retrieved April 16, 2011, from Microbiology and Immunity On-line: http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/lecture/trypanosomiasis.htm | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [4] Rudenko, G. Epigenetics and transcriptional control in African trypanosomes. <I>Essays Biochem.</I>. 2010. 20;48(1):201-19. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [5] (2007). <I>A well fed tse tse fly</I>. Retrieved April 25, 2011, from Tanzania 2007 Safari: http://www.accuratereloading.com/hr20071.html | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [6] Pottinger, P. (2010, July 27). <I>History of Chagas Disease</I>. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from History of Infectious Diseases: http://idhistory.tumblr.com/ | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [7] World Health Organization (2011). <I>Trypanosomiasis, African</I>. Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the WHO: http://www.who.int/topics/trypanosomiasis_african/en/ | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010, November 2). <I>Parasites – American Trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease)</I>. Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/ | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [9] Daniels, J.P., Gull, K. Wickstead, B. Cell biology of the trypanosome genome. <I>Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews</I>. 2010. 74;(4):552-569. | ||

<br><br> | |||

[10] Wikipedia (2011, April 11). <I>Neglected tropical disease research and development</I>. Retrieved April 16, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neglected_Tropical_Disease_Research_and_Development | |||

<br><br> | |||

[11] Foster, W. F., and Slonczewski, J. L. (2010). <I>Microbiology; An Evolving Science</I>. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. | |||

<br><br> | |||

[12] Horn, D., and McCulloch, R. Molecular mechanisms underlying the control of antigenic | |||

variation in African trypanosomes. <I> Current Opinion in Microbiology</I> 2010. 13:700–705. | variation in African trypanosomes. <I> Current Opinion in Microbiology</I> 2010. 13:700–705. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [13] Dubois, M. E., Demick, K. P., Mansfield, J. M. Trypanosomes expressing a mosaic variant surface glycoprotein coat escape early detection by the immune system. <I>Infection and Immunity</I> 2005. 2690-2697. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [14] Paulnock, D.M., Freeman, B.E., Mansfield, J.M., Modulation of innate immunity by African Trypanosomes. <I>Parasitology</I>. 2010. 137:2051-2063. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [15] Stanne, T.M., Rudenko, G. Active VSG expression sites in <I>Trypanosoma brucei</I> are depleted of nucleosomes. <I>Eukaryotic Cell</I>. 2010. 9;(1):136-147. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

[ | [16] Dagenais, T. R., Freeman, B. E., Freeman, Demick, K. M., Paulnock, D. M., Mansfield, J. M. Processing and presentation of variant surface glycoprotein molecules to T cells in African trypanosomiasis. <I>J Immunol</I> 2009. 183(5): 3344–3355. | ||

<br><br> | <br><br> | ||

Edited by student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol238/biol238syl10.html BIOL 238 Microbiology], 2011, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | Edited by student of [mailto:slonczewski@kenyon.edu Joan Slonczewski] for [http://biology.kenyon.edu/courses/biol238/biol238syl10.html BIOL 238 Microbiology], 2011, [http://www.kenyon.edu/index.xml Kenyon College]. | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | <!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Joan Slonczewski at Kenyon College]] | ||

Latest revision as of 19:30, 1 September 2011

Trypanosomes

By Kelly Wahl

The trypanosomes shown in Figure 1 are single-celled, flagellated, eukaryotic parasites responsible for African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease. The African tsetse fly (subgenus Glossina morsitans) as seen in Figure 2, transmits the strains Trypanosoma brucei gambiense and Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense through its bite [2]. In central and South America the kissing bug (subfamily Triatominae) as shown in Figure 3, spreads Trypanosoma cruzi through its feces. People become infected when feces enter the body through mucosal membranes, or broken skin (bite marks or scratches). Vertical transmission from mother to child, and infection via infected blood or organs are also routes of transmission but they are very rare. There are many other species of trypanosomes but only T. brucei, and T. cruzi are relevant to humans [3].

These parasites are part of the order Kinetoplastidia, which broke off from the common eukaryotic ancestor fairly early on. Kinetoplastids are named after the kinetoplast at the base of their flagellum. A kinetoplast is a mitochondrion with coiled mitochondrial and genomic DNA. The kinetoplast changes size and shape throughout the parasite’s life cycle and is the target site of the anti-parasitic drug ethidium [3,4].

Trypanosome Infection; Sleeping Sickness, and Chagas Disease

Sleeping Sickness

After a person is bitten they may develop a sore called a chancre and have headaches, fevers, muscle pain, joint pain, enlarged, tender lymph nodes (Winterbottom’s sign) and possibly a rash that last for about two weeks. During this first stage of infection known as the haemolymphatic stage, parasites are actively multiply by binary fission in the blood and lymph circulatory systems. Both T. b. rhodesiense and T. b. gambiense show the same clinical symptoms but symptoms are much milder in T. b. gambiense infections and usually last for a longer period of time [2,7].

The second stage of infection is neurological. Parasites have crossed the blood-brain barrier and are now multiplying in the central nervous system. classic symptoms include rapid weight loss, impaired motor skills, seizures, confusion, and changes in personality, coma, and death. A disrupted circadian rhythm is the source of this disease’s name. Patients lie awake at night but sleep during the day. Without treatment T. b. rhodesiense infections can progress so rapidly that malnutrition, heart failure, or pneumonia kill the patient before neurological symptoms ever manifest. In T. b. gambiense infections disease progression is much slower and it can take years for a person to show any neurological symptoms [2].

Chagas Disease

Chagas disease is similar to sleeping sickness in many ways. There is an acute stage and a chronic stage. One of the classic signs of acute Chagas infection is Romana’s sign, the swelling of the area around the eye where the conjunctiva (mucosal tissue around the eye) or a site near the eye was the point of infection. Patients may not present with signs of infection such as a fever as T. cruzi parasites are multiplying in the bloodstream. Serious symptoms are rare in this stage of infection but can include; heart failure, chest pain, seizures, or paralysis [8].

Unlike sleeping sickness, Chagas disease only progresses to the chronic form in 20 to 30% or people infected. The remaining 70 to 80% of people infected remain asymptomatic for life and may be unaware they are infected. As the parasite replicates in cardiac muscle and digestive smooth muscle patients develop cardiac problems such as irregular heartbeat, blood flow disorders, issues with heart muscle function, and blood clots as well as ulcers in the digestive tract [8]. Without treatment most chronic cases of Chagas disease are fatal [7].

Treatment

Symptomatic trypanosome infection is usually fatal if left untreated. There are no vaccines or prophylactic drugs to prevent infection but there are treatments available for both stages of the disease. The earlier the diagnosis, the easier it is to manage symptoms with less toxic drugs that can kill the parasite before it reaches the central nervous system.

Why Are Trypanosomes an Economic and Public Health Concern

African trypanosomes not only affects people but also livestock animals like cows, camels, horses, donkey. In animals the disease is called Nagana. In endemic areas in sub-Saharan Africa where human and animal trypanosome infections are common farmers are unable to raise cattle further contributing to malnutrition in the area. Animals can also serve as reservoirs for T. b. rhodesiense making it impossible to eradicate the endemic trypanosomiasis in humans if there are also infected cattle nearby. The behavior of the Tsetse fly vector also affects the distribution of those who are stricken by the disease. Those who rely on farming, fishing, and hunting are most at risk to be bitten by an infected tsetse fly and are also commonly the breadwinners in poor, rural populations [7]. There are estimated to be more than 70,000 cases annually in sub-Saharan Africa, which encompasses the entire geographic range of the Tsetse fly [2,3,7,9].

African sleeping sickness and Chagas disease are part of a broader group of neglected tropical diseases that have no available vaccines and the drugs used to treat these diseases either have documented drug resistance against them or are very toxic. This group of neglected diseases is projected to account for 534,000 deaths a year and millions of years of functional life lost due to disability from disease. Developing countries bore the brunt of this burden, as the human and animal tolls of these diseases stunt economic development in affected areas [10].

Domestically, Chagas is a potential risk for blood and organ transplant recipients. It is estimated that more than 300,000 people living in the U.S. are infected with T. cruzi. Most infections were picked up from countries in the Americas where the disease is endemic but, there may be cases of natural transmission in North America because of the presence of triatome species [8].

In this increasingly globalized world diseases that once hid in the jungles of South America and the plains of sub-Saharan Africa have ended up in the foyer of industrialized nations. Although trypanosomiasis is still considered a third-world disease, infections are continually being diagnosed in the first world and represent a risk to anyone that can get on a plane and travel to an affected area [2,7,8].

Transmission and Life Cycle

Life cycle

Trypanosomes cycle through five different morphological stages during their movement between arthropod vector and mammalian host [11].The morphology of trypomastigotes within the mammalian body are distinctly different from the trypomastigotes found in insects vectors because of their different metabolic needs and the presence or absence of variant surface glycoproteins (VSGs). In the midgut of the tsetse fly, after the ingestion of an infected blood meal procyclic trypomastigotes proliferate and move to the salivary gland where they differentiate into epimastigotes. The epimastigotes become VSG positive metacyclic epimastigotes. When the Tsetse fly bites a new mammalian host the metacyclic epimastigotes differentiate into a “slender” form and travel through the lymph and blood systems reproducing by binary fission in almost all organs of the body. Some of these dividing slender forms become “stumpy” and stop dividing. Although the stumpy form is no longer dividing within the mammalian host this form can survive in the fly midgut where it differentiates into the procyclic form again and completes the cycle of infection. When the parasites are in the mammalian host, numbers stages 1 through 5 in Figure 4, they are VSG positive and when they are in the Tsetse fly vector they are VSG negative [11, 3].

While T. brucei multiplies in the extracellular space between cells, T. cruzi does not have VSGs and hides from the immune system by living within host cells. T. cruzi is taken up by phagocytosis and escapes from the lysozyme into the cytoplasm with the help of a special protein that is activated at low pH [3]. Stage 3 in Figure 5 shows parasites dividing intracellularly in infected muscle cells [8].

Variant Surface Glycoproteins (VSGs)

VSGs

VSGs allow trypanosomes to remain undetected by the adaptive immune system almost indefinitely and escape the complement system. Ten million identical VSGs form homodimers with one another and cover the parasite’s cell membrane like a dense homogenous forest. Although amino acid sequences and attached sugars vary from one VSG variant to another their secondary and tertiary structures are highly conserved. Only one VSG variant is expressed at a time. There are at least 200 active VSG alleles and more than 1000 silent alleles and psuedogenes also encoding VSG variants. Active genes can recombine with silent genes to form new unique active genes. This antigenetic switching allows trypomastigotes to continually change their “appearance” to the immune system and remain undetected through the course of infection [12]. This monotypic surface coat is eventually recognized by the immune system but by the time the body is ready to react the parasite has already silenced expression of that particular VSG and begun expressing a new VSG [13]. The expression of only a single VSG also makes it difficult for complement proteins to bind and help the innate immune system catch the parasite [14].

The host immune response continually selects for the expression of new VSG variants. It is a case of the Red Queen’s race only T. brucei eventually wins as the host’s resources burn out and increasingly virulent variants are selected. There are more VSG variants than the immune system could ever recognize. VSGs can also actively modulate various components of the immune system to further avoid detection [11,12,13,14].

VSG expression

Only one of the 10-20 VSG telomeric sites expression sites is actively transcribed while the rest are silenced. Oddly enough these expression sites are transcribed by RNA polymerase I. T. brucei and other strains associated with Nangana or African sleeping sickness are the only eukaryotes that transcribe anything other than ribosomal RNA [12]. All other eukaryotes including T. cruzi only used RNA Pol I to transcribe ribosomal RNA [9].

VSGs can be mono-telomerically expressed in one of two ways. The lower left panel of Figure 6 shows transcription switching. An actively transcribed telomeric site is silenced and another telomeric site begins active transcription.

Recombination switching as shown in the lower right panel of Figure 6, is the other way T. brucei switches VSG expression [12]. One of the thousand or so silent pseudogenes recombines with an active telomeric site so it can be expressed. This type of switching greatly increases the number of possible variants. The exact proteins involved and the mechanism by which they are able to recombine is still under study but there are a number of homologs involved in homologous recombination and DNA repair that are common to trypanosomes and other eukaryotes such as yeast [12,15].

The coiling and uncoiling of chromatin determines which expression site is open for transcription while the rest are silenced. The nucleosomes, or spooling proteins that help structurally organize DNA are important for VSG expression. Expression of certain VSGs are repressed when these proteins twist DNA up in such a way that RNA polymerase cannot get to the promoter region to bind the expression site and begin transcription [12,15].

Expression site silencing requires at least six protein factors and operates by a long or short-range mechanism. In short-range silencing, acetyl groups are removed from histones within 5 KBP of the expression site by histone deacetylase SIR2rp1. The histone acetylase HAT1 reverses silencing by adding acetyl groups to histones so they bind DNA less tightly and active transcription can take place. Long-range silencing is controlled about 50 kbp upstream of the expression site most likely through chromatin remodeling with a combination of histone deacetylases, acetylases, methylases, and other enzymes.The default state for VSG expression, is silence [12].

Current Research

T. brucei’s use of ever-changing VSGs is simple and elegant but there some confounding details in the expression and alternate function of VSGs that still need to be explored. One issue is the transition from one VSG surface coat to the next. What happens as a new coat is forming and the old coat is shedding from the cell surface? There is also the question of what other tricks trypanosomes have to avoid detection by the immune system besides their VSG coats [13,10].

Expression of a Mosaic VSG Coat to Escape Early Detection by B-cells

Although only one VSG gene is expressed at a time, the surface coat isn’t always monotypic. Even though a new gene is being expressed the existing VSG coat doesn’t just disappear overnight because it takes time to transcribe, translate, and transport the new VSGs to the surface and destroy residual mRNA and protein from the previous coat. It takes about 48 hours for the VSG coat to completely switch from one variant to another [13].

Dubois et al. (2005) found the 48 hour transition period where more than one VSG variant is present on the cell surface actually prevents B-cells from recognizing either the old or new VSGs. It’s like the trypomastigote call a timeout from the B-cell response while it’s changing clothes [13].

To prove this, athymic mice (lacking T-cells) were infected with a strain of T. b. rhodesiense that had been transformed to express two VSGs at the same time. Panel A of Figure 7 shows fluorescence labeled LouTat1 VSG while panel B shows labeled 117 VSG. Panel C is an overlay of panels A and B. Wild-type trypanosomes could not be used because only a few parasites in a given population are switching coats at any one time and have mixed VSG coats. An ELISPOT assay measured the number of activated splenic B-cells producing antibodies. Figure 8 shows almost no B-cell activity in mice infected with trypanosomes co-expressing VSG 117 and LouTat1. One explanation is that B-cells are fooled by the insertion of variant VSGs in a monotypic coat during switching because the new VSGs breakup the pattern of identical epitopes required for the direct activation of B-cells void of any interactions with T-cells [13].

Trypanosomes Effects on Immune Function

Besides hiding from the immune system with an ever-changing VSG surface coat, trypanosomes also manage to down-regulate the function of various components of the immune system. one example is the decreased ability of white blood cells to process and present newly encountered antigens after trypanosome infection [16].

In 2009, Dagenais et al. showed white blood cells from infected mice displayed a decreased ability to respond to newly encountered hen egg lysozyme (HEL) antigen ex vivo. Extracted T-cells were irradiated and combined with immortal cells to form hybridomas that could be grown in cell culture. The ability to process and present an antigen was measured by the amount of interlukin-2 (IL-2) produced. IL-2 was used as a measure of immune function because it is an important cytokine that helps stimulate cytoxic T-cells and affects the development of T-cell memory, among other functions. To measure IL-2, radiolabeled thymidine was added to the hybridoma medium and the amount of IL-2 produced with incorporated radiolabeled thymidine was measured with a scintillation counter. A scintillation counter measures the amount of radiation in a sample as counts (or decays) per minute (CPM) [16].

Naïve (uninfected) cells displayed a normal dose-dependent response to the introduction of HEL. As cells were exposed to more antigen, more IL-2 was produced. Figure 9 shows constant IL-2 production in cells from infected animals regardless of the concentration of HEL or length of time the animal had been infected before T-cells were harvested [16].

Conclusion

A better understanding of the interactions between T. brucei and immune could lead to the discovery of new anti-trypanosome drugs. Current drugs available for treatment are extremely toxic with side effects that can be almost as bad as trypanosomiasis itself [10]. New anti-parasite drugs could make a huge impact on areas where sleeping sickness and Nangana are endemic. Taking control of trypanosome diseases would be a huge win for international public health and give affected areas an economic boost from increased human productivity and the ability to raise livestock [3].

References

[1] Parasite Museum (2009, June 4). Trypanosoma brucei. Retrieved April 25, 2011, from Parasite Museum: http://www.parasitemuseum.com/trypanosome/

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010, November 2). Parasites - African Trypanosomiasis (also known as Sleeping Sickness) . Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/sleepingsickness/

[3] Hunt, R. C. (2010, February 15). Parasitology-Chapter Three; Molecular Parasitology: Trypanosomes Eukaryotic cells with a different way of doing things. Retrieved April 16, 2011, from Microbiology and Immunity On-line: http://pathmicro.med.sc.edu/lecture/trypanosomiasis.htm

[4] Rudenko, G. Epigenetics and transcriptional control in African trypanosomes. Essays Biochem.. 2010. 20;48(1):201-19.

[5] (2007). A well fed tse tse fly. Retrieved April 25, 2011, from Tanzania 2007 Safari: http://www.accuratereloading.com/hr20071.html

[6] Pottinger, P. (2010, July 27). History of Chagas Disease. Retrieved April 20, 2011, from History of Infectious Diseases: http://idhistory.tumblr.com/

[7] World Health Organization (2011). Trypanosomiasis, African. Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the WHO: http://www.who.int/topics/trypanosomiasis_african/en/

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010, November 2). Parasites – American Trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas Disease). Retrieved April 1, 2011, from the CDC: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/

[9] Daniels, J.P., Gull, K. Wickstead, B. Cell biology of the trypanosome genome. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2010. 74;(4):552-569.

[10] Wikipedia (2011, April 11). Neglected tropical disease research and development. Retrieved April 16, 2011, from Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neglected_Tropical_Disease_Research_and_Development

[11] Foster, W. F., and Slonczewski, J. L. (2010). Microbiology; An Evolving Science. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

[12] Horn, D., and McCulloch, R. Molecular mechanisms underlying the control of antigenic

variation in African trypanosomes. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2010. 13:700–705.

[13] Dubois, M. E., Demick, K. P., Mansfield, J. M. Trypanosomes expressing a mosaic variant surface glycoprotein coat escape early detection by the immune system. Infection and Immunity 2005. 2690-2697.

[14] Paulnock, D.M., Freeman, B.E., Mansfield, J.M., Modulation of innate immunity by African Trypanosomes. Parasitology. 2010. 137:2051-2063.

[15] Stanne, T.M., Rudenko, G. Active VSG expression sites in Trypanosoma brucei are depleted of nucleosomes. Eukaryotic Cell. 2010. 9;(1):136-147.

[16] Dagenais, T. R., Freeman, B. E., Freeman, Demick, K. M., Paulnock, D. M., Mansfield, J. M. Processing and presentation of variant surface glycoprotein molecules to T cells in African trypanosomiasis. J Immunol 2009. 183(5): 3344–3355.

Edited by student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 238 Microbiology, 2011, Kenyon College.