Ebola: Difference between revisions

Cjackson9401 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Cjackson9401 (talk | contribs) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Uncurated}} | {{Uncurated}} | ||

[[File:Scientists_PEE.jpeg|350px|thumb|right|Scientists in protective equipment testing animal samples for Ebola Virus. Photo Credit: Content Providers(s): CDC/ Ethleen Lloyd [Public domain], via [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3A6136_PHIL_scientists_PPE_Ebola_outbreak_1995.jpg Wikimedia Commons]]] | |||

Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly pathogenic and deadly disease that has remained an enigma. Its high infection rate and mortality rate are extremely problematic since there is currently no vaccine or treatment for infection. We are currently experiencing the largest outbreak of EBOV in recorded human history. Extensive research on EBOV has shown that is largely effective because of how it induces massive immune system deregulation in infected humans. | |||

==Overview of Ebola Virus and Ebola Virus Infection== | ==Overview of Ebola Virus and Ebola Virus Infection== | ||

<br> Ebola virus belongs to the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Filoviridae Filoviridae] viral family which has three identified genera that include Ebola virus, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marburg_virus Marburg virus], and recently identified [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cuevavirus Cueva] virus<sup>1</sup>. The Ebolavirus genus itself has five identified species which include Reston Ebolavirus, Bundibugyo Ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, Taı¨ Forest Ebolavirus, and Zaire Ebolavirus<sup>1</sup>. | |||

In 1976 an outbreak of hemorrhagic fever in both Zaire and Sudan infected 550 individuals and was fatal in 430 of them<sup>6,7</sup>. The virus responsible for the outbreak was isolated from the infected patients and was found to be [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Morphology_%28biology%29 morphologically] similar to Marburg but it was also [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serology serologically] distinct<sup>6</sup>. Even after multiple outbreaks of both Marburg and Ebola, and extensive research on the different strains that have caused those outbreaks, the origin of Filoviruses still remains a mystery<sup>6</sup>. Outbreaks of Filoviruses have usually been contained in remote areas of Central Africa<sup>7</sup>. However the world is currently experiencing the largest [http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/ Ebolavirus outbreak] in its history. The outbreak is affecting Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria<sup>7</sup>. Had no interventions taken place, it was estimated that 1.4 million cases could have occur in Liberia and Sierra Leone by the beginnings of 2015<sup>7</sup>. <br> | |||

<br> | <br> | ||

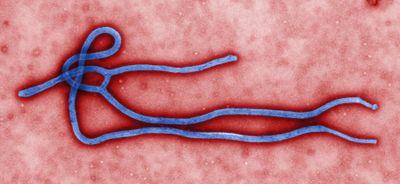

[[image:Ebola_Virus_Virion.jpeg|400px|thumb|right|Ebola virion as seen through transmission electron micrograph. By CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith [Public domain], via [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEbola_virus_virion.jpg Wikimedia Commons]]] | |||

[[image:Ebola_Virus_Virion.jpeg| | ===Morphology=== | ||

<br>Ebola can vary in length and observed optimal length as correlated to infectivity for is 970nm<sup>6</sup>. The individual virions can take many different shapes including long filaments, mace-shaped, ring, or U-shaped<sup>6,7</sup>. The virus has a diameter of 80nm and contain a [http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/nucleocapsid nucleopcapsid], an envelope derived from host cell plasma membrane [http://viralzone.expasy.org/all_by_protein/1947.html budding], and a surface layer of glycoprotein trimers<sup>6,7</sup>. EBOV is a linear negative-sense single stranded RNA virus<sup>6</sup>. EBOV is stable at room temperature, but can be inactivated by heating at 60˚C for thirty minutes, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ultraviolet_germicidal_irradiation UV irradiation], commercial hypochlorite and phenolic disinfectants, and lipid solvents<sup>6</sup>. <br> | |||

===Transmission and Host Invasion=== | |||

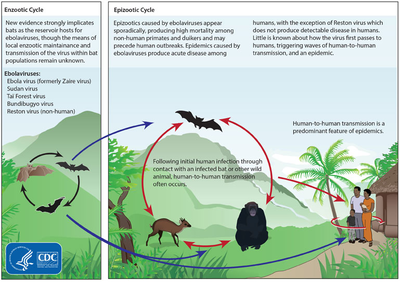

[[image:EbolaCycle.png|400px|thumb|right|Ebola virus zoonotic life cycle. By Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Public domain], via [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEbolaCycle.png Wikimedia Commons]]] | |||

<br> | |||

Ebola appears to be a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zoonosis zoonotic] disease, yet the origin of the virus family still remains a mystery and no official reservoir has been identified<sup>6,7</sup>. Current speculation points to rodent or bat reservoirs<sup>6</sup>. Data analysis suggest that fruit bats, such as Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, Rousettus aegyptiacus and Myonycteris torquata may be the reservoir<sup>7</sup>. Filoviruses are transmitted through direct contact with infected (living or dead) animals<sup>6,7</sup>. The viruses are also transmissible from person-to-person through direct or intimate contact with the infected individual or the individual’s bodily fluids<sup>6,7</sup>. | |||

Ebola can infect its hosts through breaks or abrasions in the skin, accidental injection, or through [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mucous_membrane mucosal] surfaces<sup>7</sup>. The entry process is thought to go through three phases which include cellular attachment, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endocytosis endocytosis], and fusion<sup>1,7</sup>. It is strongly believed that Ebola enters the host cells by apoptotic mimicry and is consequently [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phagocytosis phagocytosed] as part of [http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/micropinocytosis micropinocytosis] cellular response<sup>1,7</sup>. Accordingly, it is speculated that Ebola entry into host cells is enhanced by its lack of needing a surface receptor for entrance<sup>1,7</sup>. | |||

Humans are able to transmit EBOV as soon as symptoms begin to manifest<sup>7</sup>. The human body continues to be infectious throughout the course of the infection and even after death<sup>7</sup>. In the current Ebola outbreak, the majority of infected individuals range from ages 15 to 44 years of age<sup>2</sup>. Incubation period of the infection is about 11.4 days, and the disease lasts about 15.3 days, and can end in either recovery or death<sup>2</sup>. It is estimated that the current case fatality rate is 70.8%<sup>2</sup>. <br> | |||

Humans are able to transmit EBOV as soon as symptoms begin to manifest<sup>7</sup>. The human body continues to be infectious throughout the course of the infection and even after death<sup>7</sup>. In the current Ebola outbreak, the majority of infected individuals range from ages 15 to 44 years of age<sup>2</sup>. Incubation period of the infection is about 11.4 days, and the disease lasts about 15.3 days, and can end in either recovery or death<sup>2</sup>. It is estimated that the current case fatality rate is 70.8%<sup>2</sup>. <br> | |||

===Symptoms of Ebola Infection=== | |||

<br>EBOV causes acute hemorrhagic fever and illness<sup>4,6</sup>. The virus usually incubates between 4-10 days<sup>6</sup>. Post incubation the infected individual becomes abruptly ill while displaying unspecific symptoms such as severe headache, myalgia, fever, bradycardia, malaise, and conjunctivitis<sup>6</sup>. The patient quickly deteriorates over the next 2-3 days while experiencing severe nausea, pharyngitis, hematemesis, melena, prostration, and obtundation<sup>6</sup>. Further deterioration includes uncontrolled bleeding from visceral hemorrhagic effusions, as well as venipuncture sites<sup>6</sup>. Usually a maculopapular rash appears at around day 5, and death usually occurs 6-9 days after onset of the disease<sup>6</sup>. <br> | <br>EBOV causes acute [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viral_hemorrhagic_fever hemorrhagic fever] and illness<sup>4,6</sup>. The virus usually incubates between 4-10 days<sup>6</sup>. Post incubation the infected individual becomes abruptly ill while displaying unspecific symptoms such as severe headache, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myalgia myalgia], fever, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bradycardia bradycardia], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malaise malaise], and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conjunctivitis conjunctivitis]<sup>6</sup>. The patient quickly deteriorates over the next 2-3 days while experiencing severe nausea, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pharyngitis pharyngitis], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hematemesis hematemesis], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melena melena], [http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/prostration prostration], and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obtundation obtundation]<sup>6</sup>. Further deterioration includes uncontrolled bleeding from [http://en.wikivet.net/Haemorrhagic_Effusion visceral hemorrhagic effusions], as well as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venipuncture venipuncture sites]<sup>6</sup>. Usually a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maculopapular_rash maculopapular rash] appears at around day 5, and death usually occurs 6-9 days after onset of the disease<sup>6</sup>. <br> | ||

===Treatment=== | |||

<br>Currently there is no designated treatment for Ebola hemorrhagic fever<sup>6</sup>. An anti-viral drug that has been used to treat other hemorrhagic fever, Ribavirin, has shown no in vitro effect on EBOV, and is thus of little clinical value<sup>6</sup>. Passive immunity for other viral diseases has been provided to individuals suffering from an infection using human convalescent plasma; however efficacy has not been confirmed when used on patients suffering from EBOV infection<sup>6</sup>. The best care available to patients infected with EBOV is intensive supportive care to prevent shock, bacterial superinfection, hypoxia, hypotension, renal failure and cerebral edema<sup>6</sup>. | <br>Currently there is no designated treatment for Ebola hemorrhagic fever<sup>6</sup>. An anti-viral drug that has been used to treat other hemorrhagic fever, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ribavirin Ribavirin], has shown no in vitro effect on EBOV, and is thus of little clinical value<sup>6</sup>. Passive immunity for other viral diseases has been provided to individuals suffering from an infection using [http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/convalescent+serum human convalescent plasma]; however efficacy has not been confirmed when used on patients suffering from EBOV infection<sup>6</sup>. The best care available to patients infected with EBOV is intensive supportive care to prevent shock, bacterial superinfection, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypoxia_%28medical%29 hypoxia], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hypotension hypotension], [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Renal_failure renal failure] and [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cerebral_edema cerebral edema]<sup>6</sup>. | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 34: | ||

< | |||

===Ebola viral protein VP24=== | |||

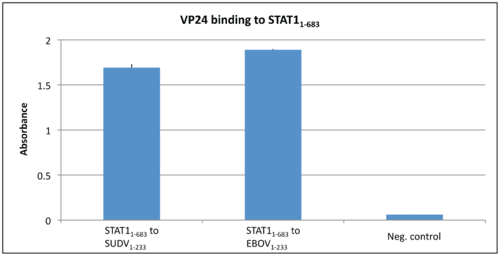

[[File:VP24.png|500px|thumb|right| Either Sudan Virus VP24 (SUDV1–233) or Ebola Virus VP24 (EBOV1–233) was coated onto the ELISA plate at 0.01 mg/ml. Plate was incubated with STAT1 and binding was detected with [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horseradish_peroxidase HRP] conjugated secondary antibody and optical density was read at 450 nm. BSA was used as the negative control. Figure provided by Zhang, Adrianna, et al. [http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1002550 PLOS Pathology]]] | |||

In a normal immune system response [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Interferon interferons] (IFNs) trigger the protective defenses of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immune_system immune system] to eliminate [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pathogen pathogens]. IFNs activate [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/STAT_protein Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcriptions (STAT) proteins], which in turn activate an immune response<sup>9</sup>. STAT1 is a crucial part of the Ebola viral infection pathway<sup>9</sup>. Normally STAT1 is [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosphorylation phosphorylated] when activated, and consequently is translocated to the nucleus via karyopherin-mediated nuclear trafficking<sup>9</sup>. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karyopherin Karyopherins], also known as [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Importin importins], are responsible for the nuclear import of proteins that are too large for diffusion across the membrane, such as STAT1<sup>10</sup>. Karyopherins have specific structural features that allow them to participate in binding. Karyopherin-α (Kapα) consists of ten helical repeats that are called armadillos (ARMs)<sup>11</sup>. ARMs 8-10 are important for Kapα binding to [http://www.jbc.org/content/282/8/5101.full classical nuclear localization signal] (cNLS)<sup>11</sup>. It had been shown in previous studies that Zaire Ebola virus protein VP24 has the ability to bind to karyopherin α1, α5, or α6. Thus Ebola protein VP24 selectively inhibits IFN-induced gene expression by sequestering nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated STAT1 since Kapα cannot bind to and translocate STAT1<sup>12</sup>. More recent research has shown that VP24 can also bind directly to STAT1, consequently blocking STAT1 translocation to the nucleus through two inhibitory mechanisms<sup>13</sup>. Zhang et al preformed an [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ELISA ELISA test] to determine if Ebola virus VP24 or Sudan Virus VP24 could bind to purified STAT1<sup>13</sup>. It can be seen that there is a strong binding affinity between STAT1 and both versions of VP24 as compared to the negative control [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bovine_serum_albumin BSA] <sup>13</sup>. | |||

< | |||

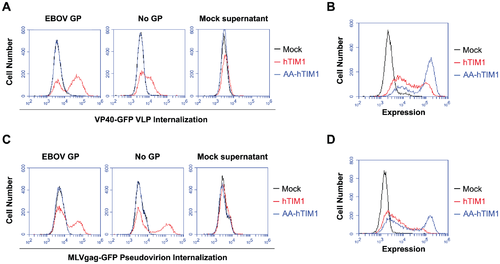

[[File:TIM.png|500px|thumb|right|Original figure legend: (A) VP40-GFP VLPs lacking any viral entry protein are bound and internalized by hTIM1. 293T cells transduced with hACE2 (mock), hTIM1 or AA-hTIM1 were incubated for 6 h with VP40-GFP VLPs bearing EBOV GP or no GP. Being inherently fluorescent, these VLPs can be detected independently of whether they undergo fusion, in contrast to the pseudoviruses and VLPs used in previous figures. The supernatant of cells expressing only GFP (mock supernatant) served as negative control. Uninternalized VLPs were detached by acid-stripping and extensive trypsinization, after which internalized VLPs were detected by flow cytometry. Figure depicts results representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicates. (B) In parallel with the infection in A, expression levels of hTIM1 and AA-hTIM1 were assessed. (C) MLVgag-GFP pseudovirions lacking viral GPs are bound and internalized at least as efficiently as those bearing EBOV GP. 293T cells transduced with hACE2 (mock), hTIM1 or AA-hTIM1 were infected for 6 h with purified and RT-activity normalized MLVgag-GFP pseudovirions. The supernatant of cells expressing only GFP (mock supernatant) served as negative control. Cell surface-bound pseudovirions were detached by acid-stripping and extensive trypsinization, after which internalized virions were detected by flow cytometry. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments performed in duplicates. (D) In parallel with the infection in C, expression levels of hTIM1 and AA-hTIM1 were assessed. Figure provided by Jemielity S, et al. [http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1003232 PLOS Pathology]]] | |||

===Ebola uses apoptotic mimicry to invade cells=== | |||

Ebola virus is very large, which can make it very difficult to enter using the classic [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clathrin clathrin] [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endocytosis endocytosis] pathway<sup>1</sup>. It is suspected that because of its size, Ebola is taken up through cellular [http://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/micropinocytosis micropinocytosis]<sup>1</sup>. Studies have shown that Ebola virus has an enriched amount of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosphatidylserine phosphatidylserine] (PS) on its surface<sup>1</sup>. PS is a type of [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lipid lipid] that is normally present in the inner leaflet of the [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cell_membrane plasma membrane] in healthy cells<sup>1</sup>. However PS is presented on the outer leaflet when the cell becomes unhealthy or is partaking in a [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Programmed_cell_death programmed cell death] mechanism<sup>15</sup>. PS on the outer leaflet signals neighboring cells to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phagocytosis phagocytose] the ‘marked’ cell<sup>15</sup>. This mechanism is mediated by TIM1 and does not produce an inflammatory or immune response<sup>14</sup>. Consequently this form of viral uptake has been termed ‘apoptotic mimicry’ and ensures that the virus will be taken into the cell without signaling the immune system<sup>1</sup>. | |||

T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain containing proteins (TIM) selectively bind to PS<sup>14</sup>. Very recent research has demonstrated that when PS receptors on [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Macrophage macrophages] are inhibited, Ebola virus entry is blocked<sup>14</sup>. This data suggests that TIM is responsible in some part for the micropinocytosis of large enveloped viruses<sup>14</sup>. Jemielity S, et al tested this hypothesis by using [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_fluorescent_protein GFP]-fused matrix proteins as [http://www.bio.davidson.edu/genomics/method/reporters.html reporters] that allow the detection of prefusion stages of viral entry<sup>14</sup>. The results of the figure provided indicate that virions bind to and internalize using TIM1 in a way that is not dependent on viral entry proteins but rather on the components of the viral membrane<sup>14</sup>. | |||

==Further Reading== | ==Further Reading== | ||

| Line 45: | Line 65: | ||

<br>[http://www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674%2814%2901293-8 1. Misasi, John, et al. Camouflage and Misdirection: The full-on Assault of Ebola Virus Disease. Cell. 2014, 159, 477-486.]<br> | <br>[http://www.cell.com/abstract/S0092-8674%2814%2901293-8 1. Misasi, John, et al. Camouflage and Misdirection: The full-on Assault of Ebola Virus Disease. Cell. 2014, 159, 477-486.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1411100 2. WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa- The first 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014, 371, 1481-1495.] <br> | <br> [http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1411100 2. WHO Ebola Response Team. Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa- The first 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2014, 371, 1481-1495.] <br> | ||

<br> [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v508/n7496/full/nature13027.html 3. Warren, Travis, et al. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature. 2014, 508, 402-405.] <br> | <br> [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v508/n7496/full/nature13027.html 3. Warren, Travis, et al. Protection against filovirus diseases by a novel broad-spectrum nucleoside analogue BCX4430. Nature. 2014, 508, 402-405.] <br> | ||

<br> [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/15/960 4. Caballero, Ignacio, et al. Lassa and Marburg viruses elicit distinct host transcriptional responses early after infection. BMC Genomics. 2014, 15, 1-12.]<br> | <br> [http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/15/960 4. Caballero, Ignacio, et al. Lassa and Marburg viruses elicit distinct host transcriptional responses early after infection. BMC Genomics. 2014, 15, 1-12.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://mbio.asm.org/content/5/6/e02011-14.full 5. Shabman, Reed, et al. Deep Sequencing Identified Noncanonical Editing of Ebola and Marburg Virus RNAs in Infected Cells. American Society for Microbiology. 2014, 5, 1-11.]<br> | <br> [http://mbio.asm.org/content/5/6/e02011-14.full 5. Shabman, Reed, et al. Deep Sequencing Identified Noncanonical Editing of Ebola and Marburg Virus RNAs in Infected Cells. American Society for Microbiology. 2014, 5, 1-11.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10024977 6. Beer, Brigitte, et al. Characteristics of Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola Viruses. Naturwissenschaften. 1999, 86, 8-17.]<br> | <br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10024977 6. Beer, Brigitte, et al. Characteristics of Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola Viruses. Naturwissenschaften. 1999, 86, 8-17.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25297522 7. Martines, Roosecelis, et al. Tissue and cellular tropism, pathology and pathogenesis of Ebola and Marburg Viruses. The Journal of Pathology. 2014, 1-75.]<br> | <br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25297522 7. Martines, Roosecelis, et al. Tissue and cellular tropism, pathology and pathogenesis of Ebola and Marburg Viruses. The Journal of Pathology. 2014, 1-75.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166354208000466 8. Bausch, Daniel, et al. Treatment of Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers: A strategy for testing new drugs and vaccines under outbreak conditions. Elsevier. 2008, 78, 150-161.]<br> | <br> [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166354208000466 8. Bausch, Daniel, et al. Treatment of Marburg and Ebola hemorrhagic fevers: A strategy for testing new drugs and vaccines under outbreak conditions. Elsevier. 2008, 78, 150-161.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1003232 | |||

<br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ | <br> [http://www.nature.com/nri/journal/v6/n8/pdf/nri1885.pdf 9. Reich, Ling. Tracking STAT nuclear traffic. Molecular Genetics and Microbiology. 2006, 602-612.]<br> | ||

<br> [http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.052705.161529?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed 10. Cook, Atlanta, et al. Structural Biology of Nucleocytoplasmic Transport. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2007, 76, 647-71.]<br> | |||

<br> [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959440X01002640 11. Chook, YuhMin, and Blobel, Günter. Karyopherins and nuclear import. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. 2011, 11:6, 703-715.]<br> | |||

<br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17928350 12. Reid, Patrick, et al. Ebola Virus VP24 Proteins Inhibit the Interaction of NPI-1 Subfamily Karyopherin α Proteins with Activated STAT1. Journal of Virology. 2007, 13469-13477.]<br> | |||

<br> [http://www.plospathogens.org/article/fetchObject.action?uri=info:doi/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002550&representation=PDF 13. Zhang, Adrianna, et al. The Ebola Virus Interferon Antagonist VP24 Directly Binds STAT1 and Has a Novel, Pyramidal Fold. Plos Pathogens. 2013. 1-12.]<br> | |||

<br> [http://journals.plos.org/plospathogens/article?id=10.1371/journal.ppat.1003232 14. Jemielity S, et al. TIM-family Proteins Promote Infection of Multiple Enveloped Viruses through Virion-associated Phosphatidylserine. PLoS. 2013, 9, 1-14.]<br> | |||

<br> [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1134557/pdf/biochemj00105-0011.pdf 15. Zachowski, A, et al. Phospholipids in animal eukaryotic membranes: transverse asymmetry and movement. Biochem. 1993. 1–14.]<br> | |||

<!--Do not remove this line--> | <!--Do not remove this line--> | ||

Edited by | Edited by Constanza Jackson, a student of [http://www.jsd.claremont.edu/faculty/profile.asp?FacultyID=254 Nora Sullivan] in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in [http://www.jsd.claremont.edu/ The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges] Spring 2015. | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Nora Sullivan at the Claremont Colleges]] | <!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Nora Sullivan at the Claremont Colleges]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:31, 14 April 2015

Ebola virus (EBOV) is a highly pathogenic and deadly disease that has remained an enigma. Its high infection rate and mortality rate are extremely problematic since there is currently no vaccine or treatment for infection. We are currently experiencing the largest outbreak of EBOV in recorded human history. Extensive research on EBOV has shown that is largely effective because of how it induces massive immune system deregulation in infected humans.

Overview of Ebola Virus and Ebola Virus Infection

Ebola virus belongs to the Filoviridae viral family which has three identified genera that include Ebola virus, Marburg virus, and recently identified Cueva virus1. The Ebolavirus genus itself has five identified species which include Reston Ebolavirus, Bundibugyo Ebolavirus, Sudan ebolavirus, Taı¨ Forest Ebolavirus, and Zaire Ebolavirus1.

In 1976 an outbreak of hemorrhagic fever in both Zaire and Sudan infected 550 individuals and was fatal in 430 of them6,7. The virus responsible for the outbreak was isolated from the infected patients and was found to be morphologically similar to Marburg but it was also serologically distinct6. Even after multiple outbreaks of both Marburg and Ebola, and extensive research on the different strains that have caused those outbreaks, the origin of Filoviruses still remains a mystery6. Outbreaks of Filoviruses have usually been contained in remote areas of Central Africa7. However the world is currently experiencing the largest Ebolavirus outbreak in its history. The outbreak is affecting Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Nigeria7. Had no interventions taken place, it was estimated that 1.4 million cases could have occur in Liberia and Sierra Leone by the beginnings of 20157.

Morphology

Ebola can vary in length and observed optimal length as correlated to infectivity for is 970nm6. The individual virions can take many different shapes including long filaments, mace-shaped, ring, or U-shaped6,7. The virus has a diameter of 80nm and contain a nucleopcapsid, an envelope derived from host cell plasma membrane budding, and a surface layer of glycoprotein trimers6,7. EBOV is a linear negative-sense single stranded RNA virus6. EBOV is stable at room temperature, but can be inactivated by heating at 60˚C for thirty minutes, UV irradiation, commercial hypochlorite and phenolic disinfectants, and lipid solvents6.

Transmission and Host Invasion

Ebola appears to be a zoonotic disease, yet the origin of the virus family still remains a mystery and no official reservoir has been identified6,7. Current speculation points to rodent or bat reservoirs6. Data analysis suggest that fruit bats, such as Hypsignathus monstrosus, Epomops franqueti, Rousettus aegyptiacus and Myonycteris torquata may be the reservoir7. Filoviruses are transmitted through direct contact with infected (living or dead) animals6,7. The viruses are also transmissible from person-to-person through direct or intimate contact with the infected individual or the individual’s bodily fluids6,7.

Ebola can infect its hosts through breaks or abrasions in the skin, accidental injection, or through mucosal surfaces7. The entry process is thought to go through three phases which include cellular attachment, endocytosis, and fusion1,7. It is strongly believed that Ebola enters the host cells by apoptotic mimicry and is consequently phagocytosed as part of micropinocytosis cellular response1,7. Accordingly, it is speculated that Ebola entry into host cells is enhanced by its lack of needing a surface receptor for entrance1,7.

Humans are able to transmit EBOV as soon as symptoms begin to manifest7. The human body continues to be infectious throughout the course of the infection and even after death7. In the current Ebola outbreak, the majority of infected individuals range from ages 15 to 44 years of age2. Incubation period of the infection is about 11.4 days, and the disease lasts about 15.3 days, and can end in either recovery or death2. It is estimated that the current case fatality rate is 70.8%2.

Symptoms of Ebola Infection

EBOV causes acute hemorrhagic fever and illness4,6. The virus usually incubates between 4-10 days6. Post incubation the infected individual becomes abruptly ill while displaying unspecific symptoms such as severe headache, myalgia, fever, bradycardia, malaise, and conjunctivitis6. The patient quickly deteriorates over the next 2-3 days while experiencing severe nausea, pharyngitis, hematemesis, melena, prostration, and obtundation6. Further deterioration includes uncontrolled bleeding from visceral hemorrhagic effusions, as well as venipuncture sites6. Usually a maculopapular rash appears at around day 5, and death usually occurs 6-9 days after onset of the disease6.

Treatment

Currently there is no designated treatment for Ebola hemorrhagic fever6. An anti-viral drug that has been used to treat other hemorrhagic fever, Ribavirin, has shown no in vitro effect on EBOV, and is thus of little clinical value6. Passive immunity for other viral diseases has been provided to individuals suffering from an infection using human convalescent plasma; however efficacy has not been confirmed when used on patients suffering from EBOV infection6. The best care available to patients infected with EBOV is intensive supportive care to prevent shock, bacterial superinfection, hypoxia, hypotension, renal failure and cerebral edema6.

Ebola Evades the Immune System

Ebola viral protein VP24

In a normal immune system response interferons (IFNs) trigger the protective defenses of the immune system to eliminate pathogens. IFNs activate Signal Transducers and Activators of Transcriptions (STAT) proteins, which in turn activate an immune response9. STAT1 is a crucial part of the Ebola viral infection pathway9. Normally STAT1 is phosphorylated when activated, and consequently is translocated to the nucleus via karyopherin-mediated nuclear trafficking9. Karyopherins, also known as importins, are responsible for the nuclear import of proteins that are too large for diffusion across the membrane, such as STAT110. Karyopherins have specific structural features that allow them to participate in binding. Karyopherin-α (Kapα) consists of ten helical repeats that are called armadillos (ARMs)11. ARMs 8-10 are important for Kapα binding to classical nuclear localization signal (cNLS)11. It had been shown in previous studies that Zaire Ebola virus protein VP24 has the ability to bind to karyopherin α1, α5, or α6. Thus Ebola protein VP24 selectively inhibits IFN-induced gene expression by sequestering nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated STAT1 since Kapα cannot bind to and translocate STAT112. More recent research has shown that VP24 can also bind directly to STAT1, consequently blocking STAT1 translocation to the nucleus through two inhibitory mechanisms13. Zhang et al preformed an ELISA test to determine if Ebola virus VP24 or Sudan Virus VP24 could bind to purified STAT113. It can be seen that there is a strong binding affinity between STAT1 and both versions of VP24 as compared to the negative control BSA 13.

Ebola uses apoptotic mimicry to invade cells

Ebola virus is very large, which can make it very difficult to enter using the classic clathrin endocytosis pathway1. It is suspected that because of its size, Ebola is taken up through cellular micropinocytosis1. Studies have shown that Ebola virus has an enriched amount of phosphatidylserine (PS) on its surface1. PS is a type of lipid that is normally present in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane in healthy cells1. However PS is presented on the outer leaflet when the cell becomes unhealthy or is partaking in a programmed cell death mechanism15. PS on the outer leaflet signals neighboring cells to phagocytose the ‘marked’ cell15. This mechanism is mediated by TIM1 and does not produce an inflammatory or immune response14. Consequently this form of viral uptake has been termed ‘apoptotic mimicry’ and ensures that the virus will be taken into the cell without signaling the immune system1. T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain containing proteins (TIM) selectively bind to PS14. Very recent research has demonstrated that when PS receptors on macrophages are inhibited, Ebola virus entry is blocked14. This data suggests that TIM is responsible in some part for the micropinocytosis of large enveloped viruses14. Jemielity S, et al tested this hypothesis by using GFP-fused matrix proteins as reporters that allow the detection of prefusion stages of viral entry14. The results of the figure provided indicate that virions bind to and internalize using TIM1 in a way that is not dependent on viral entry proteins but rather on the components of the viral membrane14.

Further Reading

Novel Nucleoside Ebola Treatement-Nature article presenting research on potential Ebola treatement.

Top Ebola Facts- CDC page on Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever.

Ebola Outbreak Updates- Doctors Without Borders latest updates on the outbreak in West Africa.

References

9. Reich, Ling. Tracking STAT nuclear traffic. Molecular Genetics and Microbiology. 2006, 602-612.

Edited by Constanza Jackson, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2015.