Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 and its environmental impacts: Difference between revisions

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

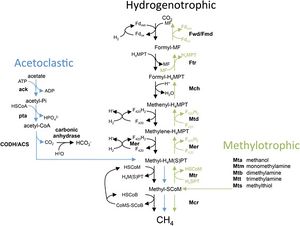

[[Image:CM1 Methanogenesis.jpg|thumb|300px|right|<b>Figure 3:</b> Three methods of methanogenesis, all of which <i>Methanosarcina barkeri</i> CM1 use. (In courtesy of Standards of Genomic Sciences).]] | [[Image:CM1 Methanogenesis.jpg|thumb|300px|right|<b>Figure 3:</b> Three methods of methanogenesis, all of which <i>Methanosarcina barkeri</i> CM1 use. (In courtesy of Standards of Genomic Sciences).]] | ||

Rumen microorganism methanogenesis has become increasingly relevant on a global scale as the raising of ruminants has become more and more commonplace. Methanogenesis occurs by methanogens residing in an animal’s rumen and hindgut. (1) Approximately 89% of ruminant-produced methane comes from the rumen and exits the animal’s body by way of the nose and mouth (Figure 4). (1) Raising animals such as cattle and sheep not only leads to a buildup of greenhouse gases, but also results in a loss of energy through the significant amount of food necessary to sustain ruminants.<ref>Lambie, S.C., Kelly, W.J., Leahy, S.C. et al. The complete genome sequence of the rumen methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri CM1. Stand in Genomic Sci 10, 57 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-015-0038-5</ref> | Rumen microorganism methanogenesis has become increasingly relevant on a global scale as the raising of ruminants has become more and more commonplace. Methanogenesis occurs by methanogens residing in an animal’s rumen and hindgut. (1) Approximately 89% of ruminant-produced methane comes from the rumen and exits the animal’s body by way of the nose and mouth (Figure 4). (1) Raising animals such as cattle and sheep not only leads to a buildup of greenhouse gases, but also results in a loss of energy through the significant amount of food necessary to sustain ruminants.<ref>Lambie, S.C., Kelly, W.J., Leahy, S.C. et al. The complete genome sequence of the rumen methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri CM1. Stand in Genomic Sci 10, 57 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-015-0038-5</ref=(1)> | ||

[[Image:Cow methanogenesis.jpg|thumb|300px|left|<b>Figure 4:</b> Methane production by methanogens in cattle and specific sources of ruminant methane emissions. Also shown is a comparison of methane emission per gram of protein for various livestock animals.]] | [[Image:Cow methanogenesis.jpg|thumb|300px|left|<b>Figure 4:</b> Methane production by methanogens in cattle and specific sources of ruminant methane emissions. Also shown is a comparison of methane emission per gram of protein for various livestock animals.]] | ||

Revision as of 20:51, 9 December 2020

Introduction

Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 is a species of methanogenic archaea of the CM1 strain, and like many other methanogens, is characterized by its production of methane as it generates energy. The Methanosarcina barkeri species has a coccoid shape and is nonmotile (Figure 1).[1] The archaea was found within the rumen of a Friesian cow on a diet of clover and ryegrass in New Zealand and since then its genome has led to discoveries in rumen methanogen diversity as well as environmental problems with the production of methane. (2)

Ruminant animals, such as this cow, through evolution have developed a digestive system that utilizes microbes to ferment plant fiber (2), as well as to produce digestible nutrients necessary for the ruminant host animal. (3) The fermentation of fibers, sugars, and starches produces carbon dioxides, methane, and volatile fatty acids. (3) Hydrogenotrophs (produce methane from hydrogen and carbon dioxide), methylotrophs (produce methane from methyl in methanol), acetoclastic methanogens (produce methane from acetate) are the three classifications into which methanogens in ruminants are grouped. (2)

Genetics

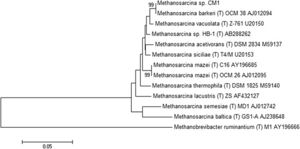

Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 is a part of the domain Archaea, the phylum Euryarchaeota, the class Methanococci, the order Methanosarcinales, the family Methanosarcinaceae, the genus Methanosarcina, the species Methanosarcina barkeri, and the strain CM1. (4) The genome of Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 is made up of an individual circular chromosome composed of 4,501,171 base pairs, and an approximate 39% guanine plus cytosine content. Approximately 70% of the genome consists of protein-coding genes at 3,523, with a 3,655 genes total. The genome also has three CRISPR gene clusters and three type I restriction/modification systems. (2) Restriction/modification systems are found in bacteria as well as other prokaryotes, and aid in preventing infection from external DNA by acting as immune systems. (5) Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 has two origins of replication within conserved genes (MCM1_3593 and MCM1_001), that are 95 kb (or 95,000 bp) apart, and does not have prophage or plasmid sequences. (2) The Methanosarcina barkeri genome is more conserved closer to the origin of replication than other Methanosarcina species. Infact, within this genus there are interspecies gene similarities up to 95%. (6) Out of the known species of the genus Methanosarcina, Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 is related most closely to Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro, another strain of the Methanosarcina barkeri species (Figure 2). (2) The CM1 strain was isolated from bovine rumen and the Fusaro was isolated from freshwater sediment, with a difference in genome size of about 0.37 Mb (the Fusaro being the larger strain). (7)

Unique to Methanosarcina species is the S-layer protein that surrounds the cytoplasm-containing membrane. (2) In a 2012 study conducted on S-layer and cell surface-layer proteins in methanogenic archaea, slmA1 genes for Methanosarcina acetivorans, Methanosarcina barkeri, and Methanosarcina mazei were both transcribed and translated at a high rate, indicating a similar control over expression of S-layer proteins. (8) In addition, the Mbar_A1758 and MA0829 proteins were found in both Methanosarcina barkeri and Methanosarcina acetivorans to be the greatest expressed S-layer protein. (8) Within the Methanosarcina barkeri species, the CM1 strain as well as the Fusaro have nine proteins that have the DUF1608 domain (2).

Also in Methanosarcina genomes are groups of nitrogenase genes. Methanosarcina barkeri is able to fix nitrogen, with the CM1 strand containing two nif operons that make up nitrogenase cofactor biosynthesis genes and nitrogenase, including the MCM1_2924-2930 nitrogenase (molybdenum and iron-containing) and the MCM1_1063-1072 nitrogenase (vanadium and iron-containing). CM1 differs from both Methanosarcina acetivorans and Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro in that its genes do not encode for the exclusively iron-containing nitrogenase. In addition, unlike Methanosarcina barkeri, there are no genes present in CM1 that enable production of gas vesicles. (2)

Microbiome & Methanogenesis

Common to both Methanosarcina barkeri CM1 and Methanosarcina barkeri Fusaro, as well as to other species of Methanosarcina and other methanogens, is the process of methanogenesis. Methanogenesis occurs in anaerobic environments, or without the presence of oxygen. (9) Methanogens (a subset within archaea) produce energy by converting certain substrates, including methanol, hydrogen with CO2, or acetate, into methane. (9) It has been found that Methanosarcina barkeri grows at the greatest rate and with the highest production on methanol. Within all of these pathways (hydrogenotrophic, acetoclastic, and methylotrophic), a methyl group is transferred to coenzyme M which is reduced to methane. (2) The CM1 strand has the genes to utilize each method of methanogenesis (Figure 3). (10)

Rumen microorganism methanogenesis has become increasingly relevant on a global scale as the raising of ruminants has become more and more commonplace. Methanogenesis occurs by methanogens residing in an animal’s rumen and hindgut. (1) Approximately 89% of ruminant-produced methane comes from the rumen and exits the animal’s body by way of the nose and mouth (Figure 4). (1) Raising animals such as cattle and sheep not only leads to a buildup of greenhouse gases, but also results in a loss of energy through the significant amount of food necessary to sustain ruminants.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Edited by [Emily Banthin], student of Joan Slonczewski for BIOL 116 Information in Living Systems, 2020, Kenyon College.

- ↑ Lambie, S.C., Kelly, W.J., Leahy, S.C. et al. The complete genome sequence of the rumen methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri CM1. Stand in Genomic Sci 10, 57 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-015-0038-5