Oral Microbiome and Cognitive Decline: Difference between revisions

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

==Introduction to the Oral Microbiome== | ==Introduction to the Oral Microbiome== | ||

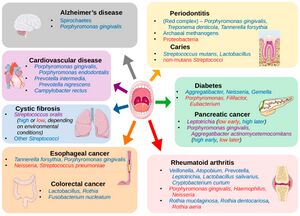

[[Image:microorganisms-08-00308-g002|thumb|300px|right|Graphical abstract representing the variety of diseases and conditions that may be connected to the oral microbiome.[https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020308].]] | [[Image:microorganisms-08-00308-g002.jpeg|thumb|300px|right|Graphical abstract representing the variety of diseases and conditions that may be connected to the oral microbiome.[https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8020308].]] | ||

The oral microbiome is a dynamic and intricate ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the oral cavity, playing a pivotal role in maintaining oral and overall health <ref name=wade>[Wade, William G. “The Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease.” Pharmacological Research, SI:Human microbiome and health, 69, no. 1 (March 1, 2013): 137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. | The oral microbiome is a dynamic and intricate ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the oral cavity, playing a pivotal role in maintaining oral and overall health <ref name=wade>[Wade, William G. “The Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease.” Pharmacological Research, SI:Human microbiome and health, 69, no. 1 (March 1, 2013): 137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. | ||

]</ref>. It comprises a diverse array of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa, with more than 700 bacterial species and 1,000 phylotypes identified to date <ref name=verma>[Verma, Digvijay, Pankaj Kumar Garg, and Ashok Kumar Dubey. “Insights into the Human Oral Microbiome.” Archives of Microbiology 200, no. 4 (May 1, 2018): 525–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3.]</ref> <ref name=deo>[Deo, Priya Nimish, and Revati Deshmukh. “Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals.” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology : JOMFP 23, no. 1 (2019): 122–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18. | ]</ref>. It comprises a diverse array of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa, with more than 700 bacterial species and 1,000 phylotypes identified to date <ref name=verma>[Verma, Digvijay, Pankaj Kumar Garg, and Ashok Kumar Dubey. “Insights into the Human Oral Microbiome.” Archives of Microbiology 200, no. 4 (May 1, 2018): 525–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3.]</ref> <ref name=deo>[Deo, Priya Nimish, and Revati Deshmukh. “Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals.” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology : JOMFP 23, no. 1 (2019): 122–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18. | ||

Revision as of 01:00, 17 April 2023

Introduction to the Oral Microbiome

The oral microbiome is a dynamic and intricate ecosystem of microorganisms inhabiting the oral cavity, playing a pivotal role in maintaining oral and overall health [1]. It comprises a diverse array of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and protozoa, with more than 700 bacterial species and 1,000 phylotypes identified to date [2] [3]. Similar to fingerprints, the oral microbiome exhibits substantial inter-individual variability, rendering it a unique and distinctive feature of each person [4].

The oral microbiome's composition and function are influenced by various factors, including genetics, diet, oral hygiene, and environmental exposures [3]. Bacterial species in the oral cavity can be broadly categorized into three groups: commensals, opportunistic pathogens, and pathogens [1]. Commensal bacteria are generally harmless and can even confer health benefits, while opportunistic pathogens may cause disease under certain conditions. In contrast, pathogens are consistently associated with disease states [2].

Recent research has emphasized the importance of the oral microbiome in human health, revealing its connection to various systemic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and even cognitive function [5] [2]. (Figure 1) Among the hundreds of bacterial species in the oral microbiome, some well-known representatives include Streptococcus mutans, associated with dental caries, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, linked to periodontal disease [3]. Other notable bacteria include the nitrogen-fixing Fusobacterium nucleatum, which plays a critical role in the development of dental plaque, and the highly diverse Actinomyces species, involved in the formation of dental biofilms [2].

The balance between pathogenic and commensal bacteria is essential for maintaining oral health, and disruptions in this equilibrium can lead to oral infections and other complications [1]. For instance, dysbiosis, an imbalance in the microbial community, can result in the overgrowth of pathogenic species, contributing to periodontitis and other oral diseases [5].

Advances in molecular techniques, such as oligotyping, have allowed scientists to explore the human oral microbiome at a higher resolution, uncovering its complex structure and interactions [4]. This deeper understanding has led to the development of novel strategies for promoting oral health, as well as the prevention and treatment of oral diseases [2].

The relationship between the oral microbiome and cognitive function is an emerging area of research. While a direct link is yet to be firmly established, there is evidence suggesting that chronic oral infections, such as periodontitis, can contribute to systemic inflammation and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may in turn affect cognitive function [5]. Furthermore, some studies have identified specific oral pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, in the brains of Alzheimer's disease patients, implying a potential connection between the oral microbiome and neurodegenerative disorders [2]. These findings highlight the need for further investigation to better understand the interplay between oral health, the microbiome, and overall well-being.

Alzheimer's Disease Overview

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, affecting millions of people worldwide and posing significant public health challenges [6]. It is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by cognitive decline, memory loss, and impaired daily functioning [7]. The exact cause of AD remains unclear, but it is believed to involve a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [8].

At the cellular level, two hallmark features of AD are the presence of extracellular amyloid plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles [7]. Amyloid plaques are primarily composed of aggregated amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, which result from the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP) by β- and γ-secretases [8]. The accumulation of Aβ peptides is thought to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD, although the exact mechanisms by which they contribute to neurodegeneration remain under investigation [6].

Increasing evidence suggests that bacteria may play a role in the development of AD. One hypothesis is that certain bacterial infections, particularly those involving the oral cavity, can induce systemic inflammation and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may contribute to neuroinflammation and the accumulation of amyloid plaques [8]. In fact, some studies have identified specific oral pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, in the brains of AD patients, supporting the potential link between oral microbiome dysbiosis and AD [7].

Given the significant public health burden of AD, understanding the potential role of bacteria and other factors in its pathogenesis is critical for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies [6]. Further research is needed to elucidate the complex interplay between the oral microbiome, systemic inflammation, and neurodegenerative processes in AD and other cognitive disorders.

Alzheimers Disease Overview

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 [Wade, William G. “The Oral Microbiome in Health and Disease.” Pharmacological Research, SI:Human microbiome and health, 69, no. 1 (March 1, 2013): 137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2012.11.006. ]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 [Verma, Digvijay, Pankaj Kumar Garg, and Ashok Kumar Dubey. “Insights into the Human Oral Microbiome.” Archives of Microbiology 200, no. 4 (May 1, 2018): 525–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00203-018-1505-3.]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 [Deo, Priya Nimish, and Revati Deshmukh. “Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals.” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology : JOMFP 23, no. 1 (2019): 122–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18. ]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 [Deo, Priya Nimish, and Revati Deshmukh. “Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals.” Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology : JOMFP 23, no. 1 (2019): 122–28. https://doi.org/10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_304_18.]

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 [Jenkinson, Howard F. “Beyond the Oral Microbiome.” Environmental Microbiology 13, no. 12 (2011): 3077–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02573.x.]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 [Ballard, Clive, Serge Gauthier, Anne Corbett, Carol Brayne, Dag Aarsland, and Emma Jones. “Alzheimer’s Disease.” The Lancet 377, no. 9770 (March 19, 2011): 1019–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9.]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 [Scheltens, Philip, et al. "Alzheimer's disease." The Lancet 388.10043 (2016): 505-517 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1]

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 [Querfurth, Henry W., and Frank M. LaFerla. “Alzheimer’s Disease.” New England Journal of Medicine 362, no. 4 (January 28, 2010): 329–44. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0909142.]

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2023, Kenyon College