Moraxella bovis: Difference between revisions

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

This nonsymbiotic aerobic pathogen prefers the moist host-habitat of the bovine ocular surface and scalar (2,5), as well as the interface of Petri dish and agar in laboratory settings (5). | This nonsymbiotic aerobic pathogen prefers the moist host-habitat of the bovine ocular surface and scalar (2,5), as well as the interface of Petri dish and agar in laboratory settings (5). | ||

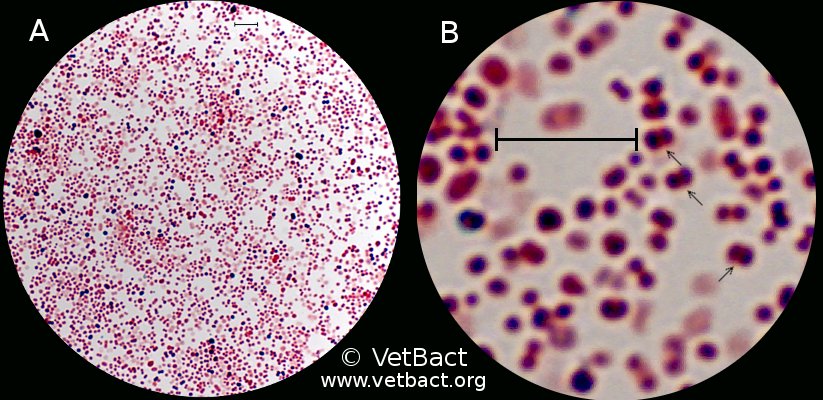

[[Image:McMichael.jpg|frame|Center|150px|Photographed and stained with Coomasie Brilliant blue, by John C. McMichael, researcher of ''M. bovis'', who found that by puncturing agar plates when planting culture allows for bacteria to grow in large flat colonies between Petri dish and agar. | |||

McMichael, John C. Moraxella Bovis – Evolution in a Petri Dish. Photograph. http://pandasthumb.org/archives/2009/11/moraxella-bovis.html . 30 Nov. 2009. Web.]] | |||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

Revision as of 18:05, 26 April 2012

A Microbial Biorealm page on the genus Moraxella bovis

Classification

Higher order taxa

Bacteria; Proteobacteria; Gammaproteobacteria; Pseudomonadales; Moraxellaceae, Moraxella (2). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=476

Species

Moraxella bovis

Description and significance

Moraxella bovis is a highly opportunistic bacterium infecting cattle herds worldwide, causing Infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivits (IBK), also known as pinkeye or ‘New Forest Eye’. This disease is characterized by inflammation and ulceration of the conjunctiva causing discomfort, excessive tearing (4) and can eventually cause ocular rupturing. This bacterium thrives on the surface of cattle eyes proliferating exponentially in the presence of oxygen and ultraviolet rays from the summer sun, which predisposes the eye to infection (4,9). IBK is transferred from cattle to cattle with flies acting as virulent vectors (5), tall blades of grass while cattle graze (7) and direct contact. Increased rates of infection occur during the summer and fall season as there is a correlation with increased sunlight and fly populations.

Genome structure

Contiguous DNA size is 15826 bp, contigs N50 (4). M. bovis has circular DNA. The DNA genome sequence of the bacterial strain Moraxella bovis Epp63 has been or is still being determined with 361 contigs read using Sanger method analysis (3).

Cell and colony structure

Moraxella bovis is a gram-negative coccobacillus, non-motile, free-living bacteria measuring between 0.6 – 1.0 µm in diameter (2,4,8), lacking flagella with varying amounts of pili. M. bovis is able to use colonial morphology (5) as a way to adapt to environmental changes. Colonies can switch between spreading-corroding (SC) and non-corroding (N) morphologies. The more virulent and common colony type is that of the SC form, which grows in flat cylindrical disk a few bacteria thick (5). Studies show that by puncturing the agar during planting allows the bacteria to adapt and grow on the interface between the Petri dish and the agar (5). Depending on the M. bovis parental cells, colony shapes thickness and dispersion differs relative to the speed of growth.

Metabolism

Being an aerobic pathogen, M. bovis uses environmentally available glucose as fuel, as well as importing essential enzymes, and uses oxygen as its electron acceptor at the end of the electron transport chain (2,8). Studies have shown that to support growth, Moraxella bovis isolates can bind bovine lactoferrin and bovine transferrin and use these proteins as a source of iron (10).

Ecology

This nonsymbiotic aerobic pathogen prefers the moist host-habitat of the bovine ocular surface and scalar (2,5), as well as the interface of Petri dish and agar in laboratory settings (5).

Pathology

Moraxella bovis causes the highly contagious disease called Infectious Bovine Keratoconjuntivitis (IBK), also known as Pinkeye. This bacterium is spread throughout a herd of cattle in the summer time, rapidly by the common black fly or by direct contact of ocular or nasal discharges (4,9). IBK is incredibly difficult to control with antibiotics or vaccinations because treatment must be administered via subconjunctival injection or with topical ointments (1). This infection affects certain breeds of cattle more severely than others, but the majority of infections occur in calves (4). M. bovis can also adapt to environmental changes, such as nutrient concentrations or changes in mesophilic temperature ranges, by differentiating with gene regulation (5). M. bovis is able to express two, possibly three, different phase variants, by adjusting colony shapes, sizes and concentrations. Colonies can switch between spreading-corroding (SC) and non-corroding (N) morphologies, depending on the concentration of nutrients, the first type being the primary isolate from the bovine eye (5) as well the most virulent. Interestingly, in studies done, shortly after a colony is isolated and grown on an agar plate the colony type switches to N forms (5), and SC forms begin to decrease in concentration. M. bovis is also able to use genotypic differentiation in order to express various pilin molecules (3), by expressing only needed amino acid sequences (5). A better understanding of the bacterial virulence and pathogenicity would be possible with a better grasp on whether the pilin adjustments or selected for or simply mutations. A theory exists that the pili aid in the secretion of hemolysin, which is the most probable cause of ocular damage, thereby allowing for M. bovis to penetrate even into the cornea and conjunctiva providing an increase in available nutrients (5) and space to grow.

References

1. Angelos, John A., V. Michael Lane, Louise M. Ball, and John F. Hess. "Recombinant Moraxella Bovoculi Cytotoxin-ISCOM Matrix Adjuvanted Vaccine to Prevent Naturally Occurring Infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivitis." Veterinary Research Communications 34.3 (2010): 229-39. Print. doi: 10.1007/s11259-010-9347-8 . http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2855018/

2. Bergey, D. H., Noel R. Krieg, and John G. Holt. Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1984. Pp 415. http://books.google.com/books?id=0-VqgLiCPFcC&q=moraxella+bovis#v=onepage&q=moraxella&f=false

3. "Genes and Mapped Phenotypes." National Center for Biotechnology Information. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Web. 19 Mar. 2012. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene

4. Highlander, Sarah K., and George M. Weinstock. "HGSC at Baylor College of Medicine." HGSC at Baylor College of Medicine. 27 June 2006. Web. 19 Mar. 2012. http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/projects/microbial/microbial-detail.xsp?project_id=123 .

5. McMichael, J. C. "Bacterial Differentiation within Moraxella Bovis Colonies Growing at the Interface of the Agar Medium with the Petri Dish." Microbiology 138.12 (1992): 2687-695. NCBI. Web. 07 Feb. 2012. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2687 . http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1362585

6. McMichael, John C. Moraxella Bovis – Evolution in a Petri Dish. Photograph. http://pandasthumb.org/archives/2009/11/moraxella-bovis.html . 30 Nov. 2009.

7. R, Craig. New Forest Eye. 2011. Photograph. http://informedfarmers.com/new-forest-eye-in-beef-cattle/

8. Rodriguez, Jose E., Abebe Hassen, and James Reecy. "Infectious Bovine Keratoconjunctivitis (Pinkeye) Study." Iowa State University, McNay Memorial Research and Demonstration Farm. Web. www.ag.iastate.edu/farms/05reports/.../InfectiousBovineKeratocon.pdf

9. Schaechter, Moselio, John L. Ingraham, and Frederick C. Neidhardt. Microbe. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology, 2006.

10. Yu, R. H., and A. B. Schryvers. "Bacterial Lactoferrin Receptors: Insights from Characterizing the Moraxella Bovis Receptors." PubMed 80.1 (2002): 81-90. Web. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11908647 .