Fungal Endophytes: Drought Tolerance in Plants: Difference between revisions

SBarnes7151 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

SBarnes7151 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

===Symbiotically derived benefits=== | ===Symbiotically derived benefits=== | ||

"some endophytes avoid stress through plant symbiosis. For example, Curvularia protuberata colonizes all nonembryonic tissues of the geothermal plant Dichanthelium lanuginosum (Redman et al., 2002; Márquez et al., 2007). When grown nonsymbiotically, neither the plant nor the fungus can tolerate temperatures above 40°C. However, the symbiosis allows both partners to tolerate temperatures up to 65°C. A similar scenario was observed with Fusarium culmorum which colonizes all nonembryonic tissues of coastal dunegrass (Leymus mollis): when grown nonsymbiotically, the host plant does not survive and the endophyte’s growth is retarded when exposed to levels of salinity experienced in their native habitat (Rodriguez et al., 2008)." [[#References |[4]]] | "some endophytes avoid stress through plant symbiosis. For example, <i>Curvularia protuberata </i> colonizes all nonembryonic tissues of the geothermal plant <i>Dichanthelium lanuginosum</i> (Redman et al., 2002; Márquez et al., 2007). When grown nonsymbiotically, neither the plant nor the fungus can tolerate temperatures above 40°C. However, the symbiosis allows both partners to tolerate temperatures up to 65°C. A similar scenario was observed with </i> Fusarium culmorum </i> which colonizes all nonembryonic tissues of coastal dunegrass (</i> Leymus mollis</i>): when grown nonsymbiotically, the host plant does not survive and the endophyte’s growth is retarded when exposed to levels of salinity experienced in their native habitat (Rodriguez et al., 2008)." [[#References |[4]]] | ||

"most, if not all, of the Class 2 endophytes examined to date increase host shoot and/or root biomass, possibly as a result of the induction of plant hormones by the host or biosynthesis of plant hormones by the fungi (Tudzynski & Sharon, 2002). Many Class 2 endophytes protect hosts to some extent against fungal pathogens (Danielsen & Jensen, 1999; Narisawa et al., 2002; Campanile et al., 2007), reflecting the production of secondary metabolites (Schulz et al., 1999), fungal parasitism (Samuels et al., 2000), or induction of systemic resistance (Vu et al., 2006)."[[#References |[4]]] | "most, if not all, of the Class 2 endophytes examined to date increase host shoot and/or root biomass, possibly as a result of the induction of plant hormones by the host or biosynthesis of plant hormones by the fungi (Tudzynski & Sharon, 2002). Many Class 2 endophytes protect hosts to some extent against fungal pathogens (Danielsen & Jensen, 1999; Narisawa et al., 2002; Campanile et al., 2007), reflecting the production of secondary metabolites (Schulz et al., 1999), fungal parasitism (Samuels et al., 2000), or induction of systemic resistance (Vu et al., 2006)."[[#References |[4]]] | ||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

|[9] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0098847206001237 Cheplick GP. 2006. Costs of fungal endophyte infection in Lolium perenne genotypes from eurasia and north africa under extreme resource limitation. Environmental and Experimental Botany 60: 202–210.]<br> | |[9] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0098847206001237 Cheplick GP. 2006. Costs of fungal endophyte infection in Lolium perenne genotypes from eurasia and north africa under extreme resource limitation. Environmental and Experimental Botany 60: 202–210.]<br> | ||

|[10] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0981942810001798 Gill, S, Tuteja N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 909-930]<br> | |[10] [http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0981942810001798 Gill, S, Tuteja N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 909-930]<br> | ||

|[11] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bies.20493/abstract Gechev, T. S., Van Breusegem, F., Stone, J. M., Denev, I. and Laloi, C. (2006), Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. Bioessays, 28: | |[11] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/bies.20493/abstract Gechev, T. S., Van Breusegem, F., Stone, J. M., Denev, I. and Laloi, C. (2006), Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. Bioessays, 28: 1091–1101.]<br> | ||

|[12] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00782.x/full Xiong, L. and Zhu, J.-K. (2002), Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25: | |[12] [http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00782.x/full Xiong, L. and Zhu, J.-K. (2002), Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25: 131–139.]<br> | ||

<!--Do not remove this line--> | <!--Do not remove this line--> | ||

Edited by | Edited by Sarah Barnes, a student of [http://www.jsd.claremont.edu/faculty/profile.asp?FacultyID=254 Nora Sullivan] in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in [http://www.jsd.claremont.edu/ The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges] Spring 2014. | ||

<!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Nora Sullivan at the Claremont Colleges]] | <!--Do not edit or remove this line-->[[Category:Pages edited by students of Nora Sullivan at the Claremont Colleges]] | ||

Revision as of 01:57, 7 April 2015

It has been estimated that over 80% of terrestrial plants form a symbiotic association with fungi.[1] Fungal endophytes have played an essential role in the evolution of land plants and remain an important component of terrestrial ecosystems. Fungal endophytes today colonize a variety of both monocot and eudicot plants which suggests this symbiosis predates the monocot-dicot split that occurred 140-150 Myr ago.[2] It is hypothesized that phototroph-fungi associations enabled plants to first colonize land and tolerate the stresses presented by their new environment. The mutualistic association could have helped them acclimate to desiccation, increased exposure to solar radiation, and more extreme temperatures differences.[3]

Fungal endophytes may benefit their host plant by acquiring nutrients, increasing plant biomass, and conferring tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Studies show that symbiotic fungi can enhance the drought, salt, and soil temperature tolerance of their host plant in addition to increasing resistance to parasitic fungi and herbivores. These habitat-adapted symbioses enable plants to thrive in harsh conditions where they would otherwise not be able to grow. Studies have shown that fungal endophytes alter plants’ growth, development, and root morphology to reduce water consumption and increase nutrient uptake. This may be used to increase crop yield in arid climates and mitigate the negative effects of climate change. Fungal endophytes have many potential applications in agriculture and conservation, yet there is still much that is not known about plant-fungi symbiosis and the mechanisms behind it.

Classes of Fungal Endophytes

Clavicipitaceous Endophytes (C-endophytes)

Class 1

C-endophytes infect the plant shoots of some grasses, form systemic intercellular infections, and are passed on through vertical and horizontal transmission.[4] Many produce alkaloids to protect their host plant from herbivory by insects and mammals, and studies have shown some class 1 endophytes to confer drought and metal tolerance.[5][8] Neotyphodium coenophialum infection, for example, results in the development of extensive root systems and longer and thinner root hairs. [8]

Nonclavicipitaceous Endophytes (NC-endophytes)

Class 2

Class 2 endophytes are usually found in the roots, stem, or leaves of their hosts.[4] They can be transmitted either vertically through the seed coat or horizontally. [4] They can confer habitat-specific stress tolerance to their hosts, and they infect a higher percentage of plants in high-stress environments.[4]

Class 3 and 4

Class 3 colonizes the shoot of plants while Class 4 colonizes plant roots.[4] Few studies have been performed on Classes 3 and 4 endophytes, and little is known about their ecological role and their ability to confer tolerance.

Reaction to Stress

Osmotic protection

Redman et al (2015) examined the osmotic concentrations in non symbiotic and heat-stress tolerant symbiotic plants. The pattern was different between the two groups, leading them to conclude that symbiotic plants do not only rely on increasing their osmolyte concentrations.[6] Endophyte known to promote drought tolerance have high levels of loline alkaloids. [7] Future experiments could test if these are present in sufficient concentration to prevent the denaturation of macromolecules or reduce the number of reactive oxygen species. [7

Reactive Oxygen Species

Abiotic stresses such as drought result in the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [10] These highly reactive metabolic products act as signaling molecules; however, when their levels are too high, they cause oxidative stress and damage proteins, lipids, and DNA. [10] [11] ROS control many plant processes such as growth, abiotic stress response, cell cycle, and programmed cell death because they influence the expression of genes. [10]

Testing Endophyte Conferred Tolerances

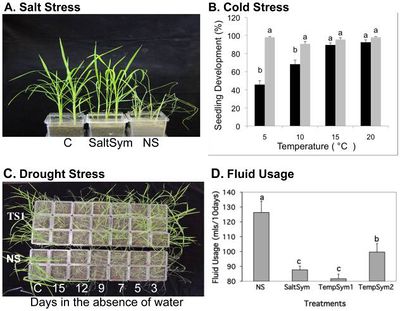

Redman et al (2015) tested how well the class 2 fungal endophytes Fusarium culmorum (SaltSym) and Curvularia protuberant (TempSym) would confer tolerance to salt, drought and cold to rice plants. SaltSym was isolated from the coastal plant Leymus mollis which is exposed to high salt stress, while TempSym 1 and 2 were isolated from Dichanthelium lanuginosum which grows in geothermal soils.

The study found that plants infected with the endophytes (S) showed no cost when grown in non-stressful conditions, but the number of colonized plants decreased from 100% to 65%.[6] When infected plants were grown in stressful environments, their water consumption decreased by 20–30% while their growth rate, reproductive yield, and biomass increased (Figure 1). [6] Non-infected plants (NS), on the other hand, lost shoot and root biomass when exposed to stress. All three endophytes treatments took 2-3 times longer to wilt than the non-infected; however, the mechanism of the conferred drought tolerance remains unknown. An interesting observation was that the endophytes changed the development of the plants to increase root biomass before shoot growth.

All plant species used in this experiment are members of the family Poacea but belong to different subfamilies. [6] The isolated fungal endophytes successfully conferred drought tolerance to the rice plants which supports the idea that the symbiotic communication needed to communicate between the fungi and the plant was conserved within the family. [6] While many fungal endophytes show habitat-adapted symbiosis, the fact that there is still lower biodiversity in high stress environments indicates that having the endophyte itself is not enough. [6]

Further Reading

References

|[1] [Smith, S., Read, D., 1997: Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 2nd edn., Academy Press, San Diego. ]

|[2] Shu-Miaw C., Chien-Chang C., Hsin-Liang C., Wen-Hsiung L."Dating the Monocot–Dicot Divergence and the Origin of Core Eudicots Using Whole Chloroplast Genomes". "Journal of Molecular Evolution". 2004. Volume 58, p. 424-441

|[3] Selosse, M-A, and F. Le Tacon. "The Land Flora: A Phototroph-Fungus Partnership?" Trends in Ecology & Evolution 13.1 (1998): 15-20. Print.

|[4] Rodriguez, R. J., et al. "Fungal Endophytes: Diversity and Functional Roles." New Phytologist 182.2 (2009): 314-30. Print.

|[5] Koulman, Albert, et al. "Peramine and Other Fungal Alkaloids are Exuded in the Guttation Fluid of Endophyte-Infected Grasses." Phytochemistry 68.3 (2007): 355-60. Print.

|[6] Redman, Regina S. et al. “Increased Fitness of Rice Plants to Abiotic Stress Via Habitat Adapted Symbiosis: A Strategy for Mitigating Impacts of Climate Change.” Ed. Hany A. El-Shemy. PLoS ONE 6.7 (2011): e14823. PMC. Web. 24 Mar. 2015.

|[7] Schardl, C. L., Leuchtmann, A. & Spiering, M. J. (2004) Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 315-340.

|[8] Malinowski DP, Belesky DP. 2000. Adaptations of endophtye-infected cool-season grasses to environmental stresses: mechanisms of drought and mineral stress tolerance. Crop Science 40: 923–940.

|[9] Cheplick GP. 2006. Costs of fungal endophyte infection in Lolium perenne genotypes from eurasia and north africa under extreme resource limitation. Environmental and Experimental Botany 60: 202–210.

|[10] Gill, S, Tuteja N. 2010. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 48: 909-930

|[11] Gechev, T. S., Van Breusegem, F., Stone, J. M., Denev, I. and Laloi, C. (2006), Reactive oxygen species as signals that modulate plant stress responses and programmed cell death. Bioessays, 28: 1091–1101.

|[12] Xiong, L. and Zhu, J.-K. (2002), Molecular and genetic aspects of plant responses to osmotic stress. Plant, Cell & Environment, 25: 131–139.

Edited by Sarah Barnes, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.