Mechanism of Antibiotic Treatment in Legionnaire's Disease: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- Do not edit this line-->{{Curated}} | <!-- Do not edit this line-->{{Curated}} | ||

== | ==Introduction== | ||

[[Image:Legionella_plate.png|thumb|300px|right| Legionella sp. streaked on a plate and viewed under UV light. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legionella].]] | [[Image:Legionella_plate.png|thumb|300px|right| Legionella sp. streaked on a plate and viewed under UV light. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legionella].]] | ||

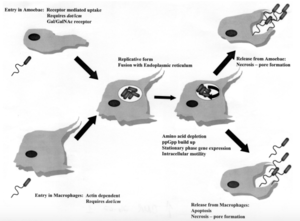

[[Image:Pathway.png|thumb|300px|right| Pathway depicting how <i>Legionella pneumophile</i> enters, replicates, and releases from amoebae and human macrophages. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legionella].]] | [[Image:Pathway.png|thumb|300px|right| Pathway depicting how <i>Legionella pneumophile</i> enters, replicates, and releases from amoebae and human macrophages. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Legionella].]] | ||

<br>By Jonathan Pang<br><br> | <br>By Jonathan Pang<br><br>Legionella is a genus of rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that inhabit fresh-water environments, with the exception of one species <i>(Legionella longbeachae)</i>, which resides in soil. Legionella have been shown to inhabit about 80% of freshwater environments, but generally only cause disease in situations where their growth rate has been enhanced by elevated temperatures (Mallegol). Legionella are not free-living bacteria. Instead, they are able to survive in freshwater and soil environments by forming commensal or parasitic relationships with protozoa. Legionella replicate intracellularly, and are thus provided with some protection from biocides, antibiotics, pH changes, changes in osmotic pressure, and thermal stress. Apart from ciliated protozoa, Legionella is also able to replicate in some species of amoebae and slime mold. There is no evidence of legionella capable of growing without a host outside of laboratory media. In humans, Legionella infects monocytes, polymorphonucelar leukocytes, and alveolar macrophages (Horwitz). Legionellosis can present clinically in three distinct ways. First, it can present as Pontiac Fever, which is a self-limited flu-like illness. Second, a person infected with Legionella can be completely asymptomatic. Last, Legionellosis can present as Legionnaires’ Disease, an illness that affects several organ systems, and is often characterized by pneumonia. There are approximately 50 species of Legionella, but roughly 90% of all cases of Legionellosis are caused by a single species, L. pneumophila. The genus Legionella contains 70 serogroups, and the species L. pneumophila is made up of 15 serogroups. However, <i>L. pneumophila serogroup</i> 1 is responsible for 84% of all cases of Legionellosis. Even though L. pneumophila serogroup 1 only makes up about 28% of environmental Legionella, it accounts for 95% of all Legionella isolated in clinical settings (Fields).<br> | ||

<br>At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.<br><br>The insertion code consists of: | <br>At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.<br><br>The insertion code consists of: | ||

<br><b>Double brackets:</b> [[ | <br><b>Double brackets:</b> [[ | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

<br><br>A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes. | <br><br>A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes. | ||

== | ==Pathogenesis== | ||

<br>The mechanisms of entrance, replication, and release for Legionella are essentially the same for both protozoa and human macrophages, but there are some key differences. In both cell types, Legionella enter the host cell either by coiling phagocytosis or convention phagocytosis. In coiling phagocytosis, temporary cytoplasmic projections known as pseudopods begin to engulf the bacterium from opposite ends of the membrane. These pseudopods come to span the circumference of the legionella cell until it is eventually engulfed (Horwitz). Typically, when this phagocytosis occurs, the engulfed microbe is digested by means of the endocytic pathway. During this process, lysosome-associated membrane glycoproteins, cathepsin D, and other acid hydrolases are recruited and function in phagolysosome formation. L. pneumophila-containing vacuoles (LCVs) delay the onset of these proteins while also recruiting ER vesicles (Newton). This takes place within 5 minutes of initial phagocytosis. After approximately 15 minutes, the membrane of the LCV becomes thinner, thus the vacuole begins to resemble the ribosome-studded ER vesicles that previously became closely associated with the membrane. At this time, Legionella converts from its stationary phase to a replicative phase, which is more resistant to the acidity of a lysosomal environment. It stops expressing the factors that delayed the endocytic pathway, which allows the LCV to merge with lysosomes. Legionella then begins to replicate with the aid of nutrients and amino acids provided by the lysosomes (Swanson). Once the amino acids of the host cell have been depleted, Legionella exits the host by causing pore formation, leading to necrosis or apoptosis. Importantly, cell death and release in human macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells is a non-productive pathway for Legionella because it does not continue to spread from person-to-person contact. Alternatively, Legionella that has infected protozoa can be released in vesicles that can continue the transmission of infection to humans if they become airborne (Fields).</br> | |||

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above. | Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above. | ||

Revision as of 18:49, 30 April 2017

Introduction

By Jonathan Pang

Legionella is a genus of rod-shaped, gram-negative bacteria that inhabit fresh-water environments, with the exception of one species (Legionella longbeachae), which resides in soil. Legionella have been shown to inhabit about 80% of freshwater environments, but generally only cause disease in situations where their growth rate has been enhanced by elevated temperatures (Mallegol). Legionella are not free-living bacteria. Instead, they are able to survive in freshwater and soil environments by forming commensal or parasitic relationships with protozoa. Legionella replicate intracellularly, and are thus provided with some protection from biocides, antibiotics, pH changes, changes in osmotic pressure, and thermal stress. Apart from ciliated protozoa, Legionella is also able to replicate in some species of amoebae and slime mold. There is no evidence of legionella capable of growing without a host outside of laboratory media. In humans, Legionella infects monocytes, polymorphonucelar leukocytes, and alveolar macrophages (Horwitz). Legionellosis can present clinically in three distinct ways. First, it can present as Pontiac Fever, which is a self-limited flu-like illness. Second, a person infected with Legionella can be completely asymptomatic. Last, Legionellosis can present as Legionnaires’ Disease, an illness that affects several organ systems, and is often characterized by pneumonia. There are approximately 50 species of Legionella, but roughly 90% of all cases of Legionellosis are caused by a single species, L. pneumophila. The genus Legionella contains 70 serogroups, and the species L. pneumophila is made up of 15 serogroups. However, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 is responsible for 84% of all cases of Legionellosis. Even though L. pneumophila serogroup 1 only makes up about 28% of environmental Legionella, it accounts for 95% of all Legionella isolated in clinical settings (Fields).

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki.

The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Pathway.png

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Introduce the topic of your paper. What is your research question? What experiments have addressed your question? Applications for medicine and/or environment?

Sample citations: [1]

[2]

A citation code consists of a hyperlinked reference within "ref" begin and end codes.

Pathogenesis

The mechanisms of entrance, replication, and release for Legionella are essentially the same for both protozoa and human macrophages, but there are some key differences. In both cell types, Legionella enter the host cell either by coiling phagocytosis or convention phagocytosis. In coiling phagocytosis, temporary cytoplasmic projections known as pseudopods begin to engulf the bacterium from opposite ends of the membrane. These pseudopods come to span the circumference of the legionella cell until it is eventually engulfed (Horwitz). Typically, when this phagocytosis occurs, the engulfed microbe is digested by means of the endocytic pathway. During this process, lysosome-associated membrane glycoproteins, cathepsin D, and other acid hydrolases are recruited and function in phagolysosome formation. L. pneumophila-containing vacuoles (LCVs) delay the onset of these proteins while also recruiting ER vesicles (Newton). This takes place within 5 minutes of initial phagocytosis. After approximately 15 minutes, the membrane of the LCV becomes thinner, thus the vacuole begins to resemble the ribosome-studded ER vesicles that previously became closely associated with the membrane. At this time, Legionella converts from its stationary phase to a replicative phase, which is more resistant to the acidity of a lysosomal environment. It stops expressing the factors that delayed the endocytic pathway, which allows the LCV to merge with lysosomes. Legionella then begins to replicate with the aid of nutrients and amino acids provided by the lysosomes (Swanson). Once the amino acids of the host cell have been depleted, Legionella exits the host by causing pore formation, leading to necrosis or apoptosis. Importantly, cell death and release in human macrophages and alveolar epithelial cells is a non-productive pathway for Legionella because it does not continue to spread from person-to-person contact. Alternatively, Legionella that has infected protozoa can be released in vesicles that can continue the transmission of infection to humans if they become airborne (Fields).

Every point of information REQUIRES CITATION using the citation tool shown above.

Section 2

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 3

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Section 4

Conclusion

References

<references /

<ref> Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. "Legionella and Legionnaires' Disease: 25 Years of Investigation." Clinical Microbiology Reviews 15.3: 506-26. </ref>

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2017, Kenyon College.