The Outbreak of Canine Parvovirus in North America: Difference between revisions

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

[[Image:Jean-yves-sgro-canine-parvovirus-protein-type-2-capsid-a-single-stranded-dna-virus.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Photographic print of Canine Parvovirus (CPV-2) viral capsid model. Courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison [http://www.organic-pet-digest.com/parvo-symptoms.html].]] | [[Image:Jean-yves-sgro-canine-parvovirus-protein-type-2-capsid-a-single-stranded-dna-virus.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Photographic print of Canine Parvovirus (CPV-2) viral capsid model. Courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Madison [http://www.organic-pet-digest.com/parvo-symptoms.html].]] | ||

<br>The Canine Parvovirus (CPV) is a deadly viral disease that leads to the enteric infection of canines via direct contact. This highly contagious pathogen has the ability to spread within 3 to 7 days to dogs in close vicinities. The viral pathogen enters the body orally and attaches itself to the villi in the gastrointestinal tract, preventing the proliferation of the host's cells | <br>The Canine Parvovirus (CPV) is a deadly viral disease that leads to the enteric infection of canines via direct contact. This highly contagious pathogen has the ability to spread within 3 to 7 days to dogs in close vicinities. The viral pathogen enters the body orally and attaches itself to the villi in the gastrointestinal tract, preventing the proliferation of the host's cells. The dying cells leads to the deterioration of the gastrointestinal tract. The effect of this enteric pathogen leads to severe dehydration, susceptibility to bacterial infections, and internal bleeding. Traveling between hosts through fecal contact, CPV outbreaks are common among canines within a close range. CPV outbreaks have been noted globally. In North America, recent outbreaks of this virus in St. Kitts and Alaska leads to the question of how determining the root of the outbreak can aid in research and prevention of the deadly disease [[#References|10]]]. | ||

==Structure and Significance== | ==Structure and Significance== | ||

Revision as of 13:58, 10 May 2018

Introduction

By Gwen Tosaris

The Canine Parvovirus (CPV) is a deadly viral disease that leads to the enteric infection of canines via direct contact. This highly contagious pathogen has the ability to spread within 3 to 7 days to dogs in close vicinities. The viral pathogen enters the body orally and attaches itself to the villi in the gastrointestinal tract, preventing the proliferation of the host's cells. The dying cells leads to the deterioration of the gastrointestinal tract. The effect of this enteric pathogen leads to severe dehydration, susceptibility to bacterial infections, and internal bleeding. Traveling between hosts through fecal contact, CPV outbreaks are common among canines within a close range. CPV outbreaks have been noted globally. In North America, recent outbreaks of this virus in St. Kitts and Alaska leads to the question of how determining the root of the outbreak can aid in research and prevention of the deadly disease 10].

Structure and Significance

The canine parvovirus strain 2 (CPV-2), or “Parvo,” is a single-stranded DNA virus, non-enveloped, that leads to a deadly enteric infection in canines. Reported globally, this virus has been sighted in New Zealand, Australia, Asia, Europe, North America, and the Caribbean and continues to kill thousands of dogs each year [1]. The first sighting of the virus surfaced during the late 1970s in Europe. The disease led to an epidemic that lasted from 1978-1979 until a vaccine was formed and the outbreak subsided. When the virus was found through electron microscopy, scientists named it CPV-2 as it held close relation to CPV-1 — a viral disease that is now placed in an entirely different category. Canine parvovirus, group II, belongs to the Parvovirus genus and the Parvoviridae family. Its higher classification is the Protoparvovirus [2].

The virulent disease may cause gastroenteritis (hemorrhagic enteritis), myocarditis, and lymphopenia in canines, among several other diseases systemically [3]. Three structural proteins, VP1, VP2, and VP3, along with NS1 and NS2, two non-structural proteins, assemble the parvovirus. The proteins come together to form an icosahedral virus, meaning that the virus contains identical subunits to form a symmetrical, equilateral triangle [1]. VP2 protein is a main structural component of CPV-2 and maintains an eight-stranded, antiparallel β-barrel. The remainder of the VP2 protein is composed of loops that attach to the β-barrel [1]. This strain originated from Feline Panleukopenia (FPLV), also known as “Feline Distemper,” a contagious and fatal disease prevalent in felines [4]. FPLV, similarly to CPV-2, is known for attacking and dividing in rapidly dividing cells [4]. FPLV is not as common due to the widespread use of the vaccine [5]. Emerging from two or more mutations of FPLV, CPV-2 mutated so that the virus could infect canine hosts.

Studying the effects of canine parvovirus aids in the further development of vaccines and other forms of prevention against this pathogenic disease. Understanding the evolution and developments of this disease initiates the protection and safety of all individuals, as it may prevent future outbreaks. Canine parvovirus is a deadly disease that requires aggressive treatment if contracted, and thus deserves the attentive research and study to keep animals and humans safe. Although it has not been noted to develop in humans, variants of this disease may one day reach the potential to do so, making the study and maintenance of CPV essential. Not only does studying the disease raise awareness, but it also improves past health concerns and keeps canine populations safe from exposure.

Symptoms and Mode of Transmission

Its mortality rate is higher in puppies (91%), ranging from six to twenty weeks old, than adult dogs (10%), as well as dogs who have not been vaccinated with the Distemper-Parvo vaccine, otherwise known as DA2PV [6]. Puppies who come into contact with the CPV-2 are at a high risk for heart failure and myocarditis. Other mammals are susceptible to CPV, such as raccoons, coyotes and wolves. The virus can resist disinfectants as well as pH and temperature, making this highly contagious virus easy to transmit [3]. Furthermore, the virus can thrive indoors and outdoor, though has more difficulty in outdoor environments [3]. CPV-2 is also most prevalent in dog and animal shelters, and can be found in fecal matter as well on other surfaces such as water bowls and dog collars [1].

The acute symptoms of CPV-2 develop within 3 to 7 days and, being highly contagious, can spread to other dogs in close vicinities. Entering the canine’s body orally or nasally, the virus lands itself in the lymph nodes [6]. Incubating for two days there, the virus reproduces in lymphocytes. Lymphocytes, white blood cells maintaining a round nucleus, pertain to the lymphatic system. The lymphatic system aids in the circulation of blood throughout the body and may lead to detrimental effects when this system begins to deteriorate. Neutropenia, which is the lack of neutrophils in the body, will also result. While some of these lymphocytes begin to die, known as lymphopenia, others travel through the bloodstream with the parvovirus [6]. The virus may then continue to spread to newer, healthier blood cells — among other rapidly dividing cells — within the body.

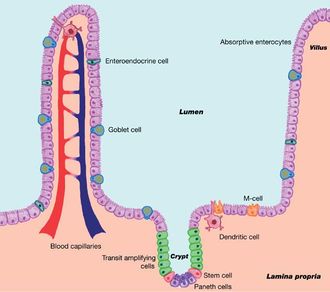

Eventually reaching the gastrointestinal tract, the virus attaches itself to the villi and continues replication on the epithelial intestinal lining. The invasion and rapid replication of CPV-2 deprives the gastrointestinal tract of nutrients and prevention fluid leakage [6]. Within the small and large intestine, the smooth muscle surrounding the lumen is lined with folds that hold the intestinal glands within the grooves. The glands, called Lieberkühn or intestinal crypts, allow for the essential, rapid creation of new cells [6]. The virus, invading the crypts, dismantles the body’s ability to replace the old cells; this may lead to mesenteric lymph nodes, crypt architectural deterioration, crypt necrosis, and villous atrophy (Figure 2) [3].Failure to absorb proper nutrients and prevent fluid loss also leads to the spread of the gut microbiome. These three things ultimately damage the intestinal surface to such an extent that it can no longer properly function. Moreover, necroscopic lesions scar and damage the intestinal surface, thickening and discoloration the lining [3]. In addition, CPV-2 leads to myocardial infection, and ultimately myocarditis and cardiac failure, as well as bone marrow degradation [6]. Within the bone marrow, the virus further weakens the white blood cell count, which gives it more of an protective advantage when entering the gastrointestinal tract.

Symptoms of canine parvovirus type 2 have a rapid onset and can be extremely contagious to others. Within days, the intestinal wall has weakened and can take five days to begin to regrow. The period of time without the immune system leads to a inflammation, internal bleeding, lack of digestion. Due to lack of digestion and lack of fluid loss into the stool, severe dehydration is a common symptom of CPV-2. In fact, dehydration becomes one of the greatest life-threats in canines with parvovirus. Other signs and symptoms include loss of appetite, as well as hematemesis and bouts of foul-smelling diarrhea. Due to severe dehydration and hypovolemia, acting lethargic or with an altered mental status is also common in dogs with canine parvovirus [6]. Bacterial infections are also possible and may lead to sepsis. Electrolyte imbalance, such as a lack of potassium, is also possible. Potassium is an essential electrolyte that relays the heartbeat and is involved in muscle contractions. Cardiac arrest may result from a lack of potassium among other electrolytes. Movement also becomes increasingly difficult for canines who have contracted the virus.

New Developments in CPV-2

Newly identified strains of canine parvovirus strain type 2 have been discovered, including CPV-2a, CPV-2b, and CPV-2c. CPV-2a is an antigenic variant of CPV-2, first discovered in 1979. CPV-2b is another strain that is most likely derived from the CPV-2a variant and is now the most common strain of canine parvovirus in North America [1]. In fact, these variants have begun to take over CPV-2 as CPV-2 has begun to disappear [7]. In fact, the CPV-2a and CPV-2b antigenic variant strains had become the predominant stains in 1984 [3]. Most recently, however, another variant known as CPV-2c has mutated from of the CPV-2 strain and has been observed in Italy, Australia, Asia and fifteen North American states since 2000[1]. This is due to an amino acid substitution in the VP2 protein that alters the Aspartic acid on the base pairs [7]. Viral shedding of a host’s fecal matter continues until the disease has been cured and is an advantageous way for the virus to expose itself to other hosts. Research suggests that the mutation occurred to better stabilize the virus in outside environments and to adapt itself to the feline species, allowing it to replicate within feline tissues [7].

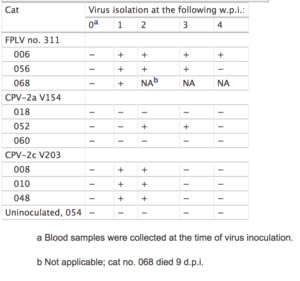

Arguably, the CPV-2c antigenic variant is not a virulent as the other strains in canines [1]. Rather, overriding CPV-2a and CPV-2b strains, this newer variant may present itself in both canines and felines and also has the potential to replace FPLV disease in felines [7]. Though CPV-2a and CPV-2b have been observed in some domestic felines in southeast Asia, its pathogenicity is relatively low and does not affect the feline as severely [9]. CPV-2c and FPLV show a decrease in white blood cells, or leukopenia, similarly to CPV-2 [7]. In response, virus-neutralizing (VN) antibodies develop. The amount of VN antibodies is lower in feline test subjects inoculated with CPV-2c compared to felines inoculated with FPLV or CPV-2a (Table 3) [7]. Mild infections of CPV-2c shows that the newer variants are increasing in pathogenicity [7]. Research continues to track this newly developed variant in order to create a vaccine that can resist the pathogenic virus. Research continues to specialize on the VP2 protein, monitored for efficacy and other mutations that strengthen the disease [10]. This is because the main structural protein, VP2, also plays a significant role in viral-host interactions [11].

Diagnosis, Treatment and Immunization

To diagnose a dog with canine parvovirus, several tests are available. The tests may be obtained from rectal swabs that are then analyzed and sequenced to determine the prevalence of the disease. Though there are several mechanisms, Haemagglutination assays (HA), ELISA assays, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR), and Nucleic Acid Sequencing are most common [1]. Next generation sequencing is another option in diagnosing canines with CPV-2 [10]. The HA test uses fecal samples and applies it onto red blood cells to observe the presence of the virus. The HA test works by taking the erythrocytes of a species and applying the virus to it. Attaching to the virus, it maintains the ability to form a lattice, thus haemagglutinating [1]. Without the virus or with a low concentration, the lattice fails to form. Though relatively simple, it requires close observation and bountiful amount of RBCs. On the other hand, Haemagglutination Inhibition assays may also be used by using antibodies to detect the presence of CPV-2.

Using PCR is the most common form of diagnostic testing currently. After being pretreated by boiling the feces, samples extracted were amplified to detect the particles. This method of identification is far more sensitive than HA, making it easier to use and better equipped to detect canine parvovirus. PCR also maintains the ability to detect CPV-2 mutants and differentiate them on the gel by using specific primers that work to identify distinct mutants [1]. Rather than use regular PCR, nested PCR is used to better identify the viral replicative form on the gel [1]. This makes it more sensitive than conventional PCR.

The most modern form of sequencing is next generation sequencing. This includes the Illumina (Solexa) Sequencing. The Illumina method is a more advanced or upgraded version of DNA sequencing that aims to read the amplified fragments of DNA. Also called “PCR on a stick,” this process allows for the development of hybridized DNA strands using chips to hold them in. It is a continuous process of denaturation and synthesization until the strand is amplified [8]. It is faster and gives a better understanding of the DNA sequences but there is still so much to be revealed about reading the entire DNA sequence together.

Once CPV has been diagnosed, supportive care and aggressive therapy work to heal the dog. Due to severe dehydration and hypovolemia as a result of vomiting and diarrhea, fluids are often given in high amounts frequently to adequately hydrate the patient [6]. Blood transfusions are also given to support the low amount of blood cells. Antibiotic drugs are also prescribed to dogs with CPV to help ward off infection.

Immunization for canines decreases the risk of infection even when exposed to the virus. Several brands of vaccinations have been produced, such as DA2PV, a vaccine that targets both CPV and Distemper, another viral disease. Some vaccines have begun to target monovalent CPV-2 and is recommended in younger canines [1]. The CPV-2 vaccine has shown to work against CPV-2a and CPV-2b and is thought to protect against the CPV-2c strain. It is now recommended that the CPV-2a and CPV-2b vaccinations are used so that new mutants in close relation may also neutralize in response to the vaccinated [1]. Veterinarians require dogs of all ages in North America to get the vaccine. However, puppies are unable to get the vaccination until they are at least six weeks of age. This is because when puppies are first born they must first build up their immune system with antibodies and other protective mechanisms to fight against pathogens. Immunity is built by their environment but also from their mother’s breast milk, the colostrum. Over time, when a puppy can withhold against the virus, the vaccine is given in a series of two booster shots. The vaccine must be given again the following year and then once every three years for the rest of life.

Outbreaks in St. Kitts and Alaska

Developments in the strain are not solely noted in feline species, but also in regions it has not surfaced in before. In late 2017, the Caribbean region noted several canines contracting the disease in that area for the first time. The outbreak imparts itself to its large and cramped canine population, raising the risk of contagion [11]. The cases of hemorrhagic gastroenteritis on St. Kitts attracted research to that particular island [11]. Focusing on the characterization of the strains in the fecal samples, the article “Molecular characterization of canine parvovirus and canine enteric coronavirus in diarrheic dogs on the island of St. Kitts: First report from the Caribbean region” (Navarro, 2017) tested and characterized the increasing prevalence of CPV in Caribbean dog populations. Using open reading frames that encode the VP2 protein, research suggests the CPV strain is most similar to the CPV-2a variant [11]. The island of St. Kitts found 24% of tested canines (out of 104 fecal samples) to have CPV [11]. Most of the dogs were within three years of age and have not been vaccinated. North America has shown increasing statistics of canine parvovirus that have most likely proliferated due to exposure from South America. In fact, though the CPV-2a strain is more common in Asia, South America and North America have increasing CPV-2b and CPV-2c variant strains. Thus, the predominance of the CPV-2a strain in St. Kitts indicates changing epidemiological factors in South and North America. Variation is one factor that results in outbreaks in North America.

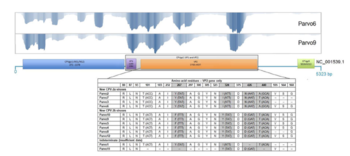

In addition, the CPV-2a strain proliferates in North American locations due to under-vaccinated canines. In 2016, an outbreak of CPV-2a and CPV-2b took place in Alaska. The outbreak, similarly to the Caribbean, may be attributed to large canine population sizes since dog sports are common in Alaska [10]. In the article “Investigation of a Canine Parvovirus Outbreak using Next Generation Sequencing” (Parker, 2017), researchers used genome-sequencing to recognize the mechanisms behind the outbreak of CPV within two canine communities; researchers tested whether or not the outbreak proliferated due to under-vaccinated canines or due to a new development in the canine parvovirus type 2 strain. VP2, being an excellent protein, provided insight to the diversity of CPV variants but also served as a base to compare to new adaptations in variants. In the study of VP2 protein in rectal samples, researchers investigated RNA transcripts and performed deep-sequencing to characterize the strains. Performing next-generation sequencing with Illumina Sequencing, (with PCR, serology and genotyping as a reference,) rectal samples were analyzed to identify any active changes of CPV in rectal samples [10]. VP2 gene location in next-generation sequencing showed the two canine communities developed two distinct virus variants, CPV-2a and CPV-2b (Figure 4). However, the rapid replication of the viruses did not suggest a new installment in the strains, but rather, suggested that the disease contaminated other dogs through nearby under-vaccinated dogs [10]. The process of next-generation sequencing determined that, not only are these viruses capable of antigenic variation but that they also maintain the ability to spread easily in places where prevention tactics and treatment are not always as accessible. The outbreaks among North America show that the disease can to infect canine populations through a combination of genomic change and under-vaccinated communities.

Public Health and Conclusion

In identifying the frequency, distribution, and main causes of disease, epidemologic research aims to prevent and control the risk factors that have an effect on the overall health and well-being of humans and animals. CPV is a deadly enteric disease that can easily spread to canines. By researching and understanding the root cause of this disease and its outbreaks, the health and safety of the community may advance and prevent its eventual return. Moreover, researching CPV enables public health and safety to improve in the overall understanding of medicine and disease control and prevention; honing in by studying certain aspects of disease, such as its pathogenesis and outbreak trends, can alter and elucidate the current scientific perspective of the pathological world. By studying outbreaks and epidemics, researchers may also conclude new ways to prevent the transmission of diseases on a national and global scale.

Though CPV is not currently transmissible to humans, maintaining animal health still affects humans with respect to their support in the food and nutrition industry as well as therapeutically in the home. The advantages to maintaining animal health reduces the risk of exposure to canine parvovirus as well as to other diseases that develop in animals that are not properly cared for. By taking domestic animals to the veterinarian, vaccinating them, and establishing baseline health, both the animal and human community are protected and safe. If canine parvovirus contamination is likely in one’s house or yard, it is important to remember that the disease is robust and difficult to dispel. However, bleach is one household item that does work against CPV and can be used to disinfect contaminated areas. Removing and preventing the spread of the contagion is important in the consideration of its rapid evolution; the canine parvovirus and variants of this disease may reach the potential to one day transmit to the human species as a zoonotic disease. Thus, the effort to maintain a healthy space remains essential. Both individually and communally, precautions must be taken to cure and prevent the propagation of canine parvovirus.

It is important to address public health concerns in North America as well as on an international scale. Though North America continues to progress in western medicine and in disease control, there are variables that prevent complete isolation of diseases. In areas with fewer resources available, maintaining a healthy environment becomes increasingly difficult. Thus, dangerous pathogens continue to circulate and play a role in the epidemics and outbreaks that can extend to individuals across borders and on a global scale. By working to improve and advance in vaccines and other cures at affordable costs, preventative care can be possible and may improve the well-being of animals and humans worldwide.

References

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2018, Kenyon College.

[7]

[8]

[9]

[10]

[11]

- ↑ Nandi, S., and Manoj Kumar. “Canine Parvovirus: Current Perspective.” Indian Journal of Virology : an Official Organ of Indian Virological Society, Springer-Verlag, June 2010

- ↑ Meunier, P.C., et al. “Pathogenesis of Canine Parvovirus Enteritis: The Importance of Viremia.” Veterinary Pathology, Sage Journals, 1 Jan. 1985.

- ↑ “Canine Parvovirus - Digestive System.” Merck Veterinary Manual, Merck Manual

- ↑ “Distemper in Cats.” PetMD, LLC. 1998-2018.

- ↑ Squires, Richard A. “Overview of Feline Panleukopenia - Generalized Conditions.” Merck Veterinary Manual, Merck Manual.

- ↑ “Canine Parvovirus.” Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, 29 Jan. 2018

- ↑ Kazuya, et al. “Pathogenic Potential of Canine Parvovirus Types 2a and 2c in Domestic Cats.” Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology, American Society for Microbiology, 1 May 2001

- ↑ Slonczewski, Joan, and John Watkins. Foster. Microbiology: An Evolving Science. New York: W.W. Norton, 2017. Print.

- ↑ Ikeda Y., Mochizuki M., Naito R., Nakamura K., Miyazawa T., Mikami T., Takahashi E., (2000) Predominance of canine parvovirus (CPV) in unvaccinated cat populations and emergence of new antigenic types of CPVs in cats. Virology 278:13–19.

- ↑ Parker, Jayme, et al. “Investigation of a Canine Parvovirus Outbreak Using Next Generation Sequencing.” Nature News, Nature Publishing Group, 29 Aug. 2017.

- ↑ Navarro, Ryan, et al. “Molecular Characterization of Canine Parvovirus and Canine Enteric Coronavirus in Diarrheic Dogs on the Island of St. Kitts: First Report from the Caribbean Region.” Virus Research, Elsevier, 26 Aug. 2017.