Phage Therapy: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

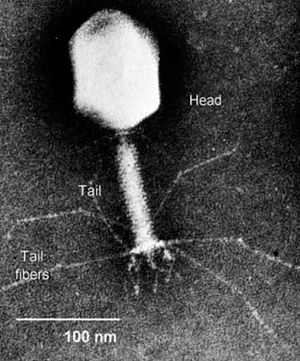

[[Image:Bacteriophage2.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Electron micrograph of a bacteriophage. Source: bio.davidson.edu.]] | [[Image:Bacteriophage2.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Electron micrograph of a bacteriophage. Source: bio.davidson.edu.]] | ||

Revision as of 18:31, 18 April 2010

Introduction

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria. Bacteriophages have many potential applications in biotechnology that are currently being explored such as being used as delivery vehicles for vaccines and gene therapy, detecting bacterial pathogens, and as a way to screen libraries of peptides or antibodies. Phage therapy takes advantage of this particular group of viruses in a relatively simple way; it aims to treat bacterial infections through the application of such phages.

Though for some time people did not consider this use of bacteriophages feasible, since the emergence of many antibiotic-resistant pathogens, then field is again on the rise (Inal 2003). Recent WHO figures suggest that 14,000 people die in the US alone every year due to multidrug-resistant bacteria acquired in hospitals. Luckily, bacteriophages are found in all bacteria so the is at least a theoretical possibility that therapies can be developed for all species of bacteria (Inal 2003). Because humans are unlikely to be able to come up with novel antibiotics forever and bacteria will probably continue to evolve resistances, from the human perspective it is important that new ways of thwarting infection are discovered.

It seems that bacteriophages may be the knight in shining armor for the treatment of bacterial infections (Summers 2001). They are specific to their bacterial host and therefore do not harm humans or plants, they can grow in numbers as long as the bacteria are present, and they are self-limiting in that once they kill all of the target bacteria they no longer have a place to live and they die off too.

History

Early research

Phage therapy was first attempted soon after the discovery of bacteriophages in about 1919, but some early inconsistent and unsuccessful results led to a waning of research interest, especially in the West (Clark and March 2006). Antibiotics were also being discovered around this time, which looked more promising, so research on bacteriophages only continued in some parts of the world (Inal 2003). This has led to the emergence of Georgia as the forerunner in phage therapy.

Early issues

There are several reasons why the early trials in bacteriophage therapy were unsuccessful (Weld et al 2004). For one, phage biology was poorly understood, and therefore the wrong phage or the wrong concentration of phage may have been given to treat an infection. Another limiting factor to the success of early therapeutic uses of phage is that the preparations of phage to be administered were all too commonly contaminated or did not contain enough viable viruses to be effective. Lastly, early attempts were not consistently effective because sometimes the wrong phage would be employed or they would choose phage-resistant bacteria to study. Current thinking to avoid this issue involves using cocktails of slightly different bacteriophages to target all of the pathogenic bacteria, even those with mutations or plasmids protecting them from certain phage. Though it is less likely that these same mistakes will be encountered in current use of bacteriophages in a therapeutic setting, there still need to be significant research programs undertaken before phage therapy will be fit for widespread use (Weld et al 2004).

Current research and potential problems

Though current research appears promising and it seems that phage therapy may be a good solution to the problem of multidrug resistant bacteria, there is a long way to go before the therapy is ready to be applied on a widespread basis. One current issue is that many of the experiments that are done are in vitro, meaning that the same things that are observed may not be seen when ones goes to a larger and more complicated environment (Weld et al 2004). New growth models are needed that can be extrapolated to in vivo growth. Weld et al (2004) attempted to make new models for phage growth, but quickly found that bacteriophages have a far more complicated growth cycle in vivo. They found not only that it was difficult to extrapolate from in vitro to in vivo, but also that it was hard to make generalizations about all in vivo situations from observing one (Weld et al 2004).

It is clear that all

Mechanism of action

Delivery to targeted pathogens

When phages were first discovered and applied in a clinical setting for the treatment of diseases, they were injected in the vicinity of the infection. Later mechanisms of delivery included topical administration 3 times a day, eye drops, or orally before meals (Inal 2003). Phages, unlike many antibiotic molecules, are not diffusible across membranes and must therefore have a method of delivery to the target cells. Some researchers believe that the best delivery mechanism may lie in using other nonpathogenic species of bacteria to bring the phage to its pathogenic target.

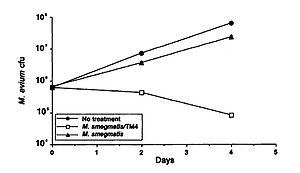

A study by Broxmeyer et al (2002) investigated the effectiveness of phage treatment of an intracellular human pathogen by using a mouse model. The study tested the ability of a mycobacteriophage delivered by a nonvirulent mycobacterium to kill Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. These disease are common in sufferers of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), and though there have been some advancements in treatment in recent years, their effectiveness is limited by drug resistance and the fact that most of their modes of action require that the target is not in a dormant period. The researchers used vacuoles within macrophages to deliver the phage and found that treatment of M. avium-infected and to an even greater extent M. tuberculosis- infected cells with the phage resulted in decreased bacterial numbers (Figure 1). They capitalized on the fact that infecting macrophages with both M. avium and Mycobacterium smegmatis (the delivery bacteria for the TM4 lytic phage) leads to fusion of the vacuoles of the two, which in turn results in delivery of the phage to the target pathogenic bacteria. A decrease in M. avium number was seen when treated with the delivery bacteria, but a far greater decrease was seen when it was coinfected with the delivery bacteria plus the TM4 phage (Figure 1). (Broxmeyer et al 2002).

This study provides promising support to the potential for the use of other bacteria as a delivery mechanism for bacteriophages to treat pathogenic diseases.

Some researchers have categorized different delivery modes as 'passive' and 'active'. Passive delivery is achieved by administering large doses of phage that likely exceed how many bacteria are present. Active delivery, on the other hand, involves making sure that the phage lives long enough to generate progeny cells which will then kill the bacterial cells. This latter category has the advantage that it can act over a longer period, but it may be difficult to realize fully because new doses must be administered at key time intervals. A study by Platt et al (2003) tried to employ a lysogenic life cycle such that cells would burst periodically and release phage into the environment. They used a non-pathogenic strain of E. coli that was lysogenic for a lytic mutant. They suggest that this is the best way to constantly release phage into the environment. They also say that this system may get around the issue of phage-resistant mutants by including different lysogens for different receptors on the target pathogen (Platt et al 2003).

Comparison to antibiotics

Though phage therapy aims to do the same thing as antibiotics in treating bacterial infections, they have different mechanisms and therefore different associated advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Disadvantages

text

The future of phage therapy

Possible novel uses

Include some current research, with at least one figure showing data.

Obstacles

Conclusion

Overall text length at least 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures.

References

Broxmeyer, L., Sosnowska, D., Miltner, E., Chacon, O., Wagner, D., McGarvey, J., Barletta, R.G., and Bermudez, L.E. "Killing of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium tuberculosis by a Mycobacteriophage Delivered by a Nonvirulent Mycobacterium: A Model for Phage Therapy of Intracellular Bacterial Pathogens". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002. Volume 186, Number 8. p. 1155-1160.

Clark, J.R. and March, J.B. "Bacteriophages and biotechnology: vaccines, gene therapy and antibacterials". TRENDS in Biotechnology. 2006. Volume 24, Number 5. p. 212-218.

Inal, J.M. "Phage Therapy: a Reappraisal of Bacteriophages as Antibiotics". Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2003. Volume 51. p. 237-244.

Platt, R., Reynolds, D.L., and Phillips, G.J. "Development of a novel method of lytic phage delivery by use of a bacteriophage P22 site-specific recombination system". FEMS Microbiology Letter. 2003. Volume 223. p. 259-265.

Summers, W.C. "Bacteriophage Therapy". Annual Review of Microbiology. 2001. Volume 55. p. 437-451.

Weld, R.J., Butts, C., and Heinemann, J.A. "Models of phage growth and their applicability to phage therapy". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2004. Volume 227. p. 1-11.