THE DIAGNOSIS OF SYPHILIS

Introduction

By [Heather Fantry]

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection that has been rising in prevalence since 2000 (CDC, 2013). It is caused by the spirochete

Treponema pallidum.

T. pallidum is a thin, tightly coiled spirochete that is microaerophilic (Tramont, 2005). Unlike most bacteria that infect humans, it cannot be cultured in the laboratory. It can only be cultured in laboratory animals, usually rabbits, which are not readily available in hospitals or medical clinics. Hence the diagnosis of syphilis is extremely difficult.

Clincial Signs and Symptons

Before understand how to diagnose syphilis, it is important to know about the stages of disease since different methods may be used for different stages. Primary syphilis h occurs 9-90 days after contact with T. pallidum (Tramont, 2005). It is manifested by a skin lesion called a chancre Figure 1) (CDC, 2013). It starts out as flat area of redness that develops into a bump and then into a swallowing opening in the skin. The chancre occurs at any place on the body in which an individual has had contact with T. pallidum. This is usually on the penis in a man or external genitalia in a woman but can be in the mouth or even on a finger.

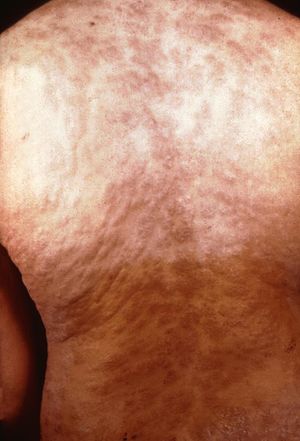

The next stage is secondary syphilis. This occurs 3-10 weeks after the initial lesion if a person is not treated with antibiotics (Tramont, 2005). This means that T. pallidum has spread throughout the body. The most common symptom is a non-itchy rash that is not raised and often is on all parts of the body (Figure 2). Other manifestations can include fever, headache, weight loss, lymph node swelling, loss of hair, and eye disease. Individuals also may develop condyloma latum which are flat bumps in the genital area which have lots of T. pallidum and are very infectious. In addition, individuals can get flat patches in their mouth called mucous patches.

The third stage is latent syphilis (CDC, 2013). It has no signs or symptoms and the only manifestation of the disease is a positive blood test.

The final stage is tertiary syphilis which only occurs in 35% of untreated patients (Tramont 2005). It occurs 10-25 years after primary syphilis. Most commonly it causes disease of the nervous system but it also can cause heart disease or deposits in the skin, soft tissue, or bones called gummas. The neurological manifestations are meningitis, strokes, dysfunction of cranial nerves, dementia, difficulty walking, visual or auditory problems, and loss of vibration sense.

T. pallidum can be transmitted from a mother to her unborn child which is called congenital syphilis (CDC, 2013). Although rare in the United States, it is of great concern because it can cause deafness, neurological problems, bone deformities, and even death (CDC, 2013).

Who Should be Tested for Syphilis?

Individuals with any of the signs and symptoms of syphilis should be tested for syphilis (CDC, 2014). In addition, persons with no symptoms but are at risk for syphilis should be tested. This includes persons whose have multiple sexual partners, use illegal drugs, use alcohol, have unprotected sex, and are prostitutes. It also includes men who have sex with men, prisoners, and HIV-infected patients. In addition, anyone who has a sexual partner that has syphilis should be tested. Finally, women who are pregnant should also be tested because of the risk of transmission to their infant.

Knowledge of the syphilis epidemic also is helpful (Figure 3). Syphilis is most common in urban areas and the south so any sexually active person should be tested in these areas. The state with the highest rate is Maryland.

Direct Diagonsis

Microscopy

The most sensitive and quickest method to diagnose primary syphilis is microscopy (Tramont 2005). A swab is place in the chancre and T. pallidum attaches to the swab and can be viewed under a microscope. However, T. pallidum is so thin (0.1 µm) that it cannot resolve light and can only be detected by light scattering which requires a special darkfield microscope. Under darkfield microscopy, T. pallidum will look like a corkscrew rapidly turning around its midpoint (Slonczewski and Foster, 2014 and Tramont, 1995) (Figure 4). However, a dark field microscope requires skilled technicians and is so expensive that it is not readily available at hospitals or other medical facilities (Tramont, 1995).

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)

Another direct method that is available to diagnose syphilis is PCR. PCR is used to amplify sections of T. pallidum DNA which was fully sequenced in 1998 (Fraser et al, 1998). It can be used to diagnose primary syphilis by taking a swab from the chancre. This method has been showed to be 82% sensitive and 95% specific (Grange et al, 2012). It can also be used to diagnose secondary syphilis using a blood sample and to diagnose congenital syphilis using frozen or formalin fixed placental tissue (Genest et al, 1996 and Heymans et al, 2010). However, T. pallidum PCR is not readily available in the United States and specimens have to be shipped to the CDC (CDC, 2015) Submission requires special approval by the local health department and the turnaround time is two weeks.

Antibody Tests

Since dark field microscopy is only useful for primary syphilis and not readily available and PCR is primarily used for congenital syphilis and also not readily available, the primary methods for diagnosing syphilis are antibody tests. They can be divided into nontreponemal and treponemal tests.

Nontreponemal Antibody Tests These test measure IgG and IgM antibodies nonspecific antibodies that are present in persons with syphilis directed against a cardiolipin-lecithin –cholesterol antigen that is released from T. pallidum or when T. pallidum interacts with human tissue (CDC, 2013). They do not measure direct antibodies against T. pallidum itself. The most commonly used nontreponemal antibody tests are the rapid plasma reagin (RPR) card test, automated regain test (ART), and toluidine red unheated test (TRUST). In addition, there is also now a modified RPR test which is a point-of-care test which means that it can be done where the patient receives care such as a clinic, doctor’s office or emergency room (Peeling RW et al, 2006).

Both the RPR and VDRL are quantitative results (CDC, 2013). The higher the titer, the higher dilution that the test was still positive and hence the more antibody present. The quantity of antibodies correlates with disease activity. Dilutions are report in 1:2n+1. For example, results can be 1:1 (20), 1:2 (21), 1:4 (22), or 1:16 (23). A titer or 1:1 is correlated with low disease activity while a titer of 1:256 is correlated high disease activity.

Nontreponemal antibody tests are most useful during secondary syphilis because they are positive in 100% of infected individuals (Figure 4) (CDC, 2013). They can also be used to diagnose primary and tertiary syphilis but they may be falsely negative in up to 29% to patients. In primary syphilis, antibodies may not have had time to develop. In tertiary syphilis, titers decline with time. In addition, because these tests are nonspecific, they also can produce false positive results. Other bacterial infections, viral infections including HIV, injections drug use, vaccination, and autoimmune diseases can produce positive results even when T. pallidum is not present. All positive nontreponemal tests need to be confirmed with a specific treponemal test.

Treponemal Immunofluorescent Antibody Tests Until recently, there were only three antibody tests that specifically measured antibodies to T. pallidum (Tramont, 2005). These were the fluorescent treponemal antibody-absorbed (FTA-abs), T. pallidum Haemagglutination Assay (TPHA) and Microhemagglutination Assay for Antibodies to T. pallidum (MHATP). The most commonly used test is the FTS-abs. It uses T. pallidum taken from rabbit testes and is a standard immunofluorescent antibody test in which an antibody is labeled with a compound that fluoresces. Since nonpathogenic treponemes are in the mouth and genital tract of humans, the antibodies against these treponemes need to be removed by a “sorbent” which is a nonpathogenic antigen. The patient’s serum is then placed on slide with a T. pallidum antigen and fluorescein-labeled antihuman gamma globulin is added to the slide. If there are antibodies to T. pallidum, the slide will fluoresce when viewed in fluorescence microscope.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Recently, another type of specific antibody test called the syphilis ELISA has come into widespread use. It is performed by coating the wells of a plastic laboratory dish with T. pallidum (Slonczewski and Foster, 2014). If antibodies to T. pallidum are present, then they will bind with the T. pallidum. Unbound antibodies in the serum are washed away and another antibody linked to an enzyme that binds to the T. pallidum antibodies is added to the dish. When a substrate for the enzyme is placed in the dish, the enzyme produces light or a colored product only in the wells that have antibody to T. pallidum. There will be no light in the wells without T. pallidum antibodies. The sensitivity of the ELISA is 93% which is greater than other antibody tests (Figure 5) (CDC, 2013).

Because ELISA tests to diagnose syphilis are less expensive than nontreponemal antibody tests when performed on large numbers of samples, some sexually transmitted disease clinics and blood banks screen with an ELISA test (CDC, 2008, CDC, 2010). Unlike nontreponemal antibody tests, there is no titer given so it cannot distinguish between appropriately treated past infection and infection that requires treatment (CDC, 2010). It is recommended in these cases that a nontreponemal test be used for confirmation and to make treatment decisions.

Reverse enzyme-linked immunospot assay (RELISPOT) In the late 1990, enzyme linked immunospot assays were developed in an attempt to differentiate active syphilis from treated syphilis (Tabidze, 1999). In these assays, blood mononuclear cells are collected and tested for T. pallidum-specific circulating antibody-secreting cells by an enzyme-linked immunospot assay (ELISPOT). This type of assay enables visualization of products secreted by human immune cells (Wikipedia, 2014). Each spot on the assay represents a single reactive cell. Some early work showed that they were positive in 100% of patients with primary syphilis, 87% of patients with secondary syphilis, and 46% of patients with latent syphilis. However, there is no mention of this test in later papers or in current recommendations for diagnosing syphilis (CDC, 2014, CDC, 2013, CDC, 2010).

However, a reverse enzyme-linked immunospot (RELISPOT) is now used for the diagnosis of congenital syphilis. This tests is based on a localized enzyme-substrate reaction using petri dishes coated with antibodies (Czerkinsky, 1984). Similar to the ELISPOT, the RELISPOT can be used to give a quantitation of secreted antigen. It’s major use in syphilis is to distinguish active infection in the newborn from passive transfer of antibodies from the mother to the infant (Stoll et al, 1993). Stoll et al found that sensitivities of the RELISPOT were not as high as the IgM ELISA or FTA-abs but its specificity was >96%.

Immunochromatographic Tests Immunochromatographic tests for syphilis are referred to as immunochromatographic membrane tests (ICT) or immunochromatographic strip (ICS). Serum is placed on a cellulose strip bound with anti-human immunoglobulins and/or purified T. pallidum antigens (Slonczewski and Foster, 2014). If there are antibodies in the patient’s serum, there is a color change which is visible to the naked eye. Sensitivity and specificity are between 85% and 98% when compared to other antibody tests (Herring A, 2006, Slonczewski and Foster, 2014). Immunochromatographic tests are point-of-care tests that do not require a laboratory can be done where the patient receives medical care. Staff require minimal training and the test are inexpensive. Results are available in 15 minutes or less so that patients can be notified immediately of their results.

Until recently, none of these tests were approved by use in the United States so they were used primarily in developing countries. However, in 2014 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved an immunochromatographic test called Syphilis Health Check (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2014).

The manufactures of this test claim 98% agreement with other treponemal tests (Diagnostics direct, 2011).

Line Immunoassay (LIA) The LIA uses T. pallidum recombinant and synthetic polypeptide antigens to determine if a patient’s blood has treponemal antibodies (Hagedon HJ, 2002). Similar to the immunochromatographic tests, it is a point-of-care test that is inexpensive, rapid, and requires little training to read. It is used in developing countries. The sensitivity and specificity of the LIA were 100 % and 99 %, respectively (Hagedon HJ, 2002).

Dual Treponemal/Nontreponemal Test

The most recent development in syphilis testing is the development of a syphilis point-of-care tests that combines a treponemal and nontreponemal antibody test. This means that the patient does not have to wait for a confirmatory test as with the other tests. The test is called the DPP Syphilis Screen and Confirmation Assay. A recent study showed that the sensitivity was 89.8% and specificity was 99.3% when compared with immunoassay and RPRs. However, it has not been approved by the FDA and thus is not available yet for use in the United States. (Causer LM, 2015)

References

[1] Hodgkin, J. and Partridge, F.A. "Caenorhabditis elegans meets microsporidia: the nematode killers from Paris." 2008. PLoS Biology 6:2634-2637.

Authored for BIOL 238 Microbiology, taught by Joan Slonczewski, 2015, Kenyon College.