Vinification, flavor, and aroma

Wine making, or vinification is a process, through which fruit juice, usually from grapes, is fermented to produce an alcoholic drink. Once fruit is harvested, it is the wine makers duty to ferment the juice into a palatable wine through complex interactions of yeast and bacteria. Fermentation can be achieved using the natural grape must, naturally occurring yeast on machinery and vines, or by inoculating batches with commercially produced yeasts. Vinification requires the careful management of the microflora present, nutrient availability for the microflora, pH, temperature, and storage conditions, in order to make a palatable vintage.

The perception of a wine’s flavor and aroma comes from a multitude of interactions between about a 1,000 chemical compounds within the wine and our own sensory receptors. These chemical compounds function in many different ways, and can act synergistically or antagonistically with each other. Flavor and aroma compounds are derived from the grapes themselves, the wood fermentation occurs in, and the metabolites of microbes used in the fermentation process. Making a tasty wine is largely related to the ratios of volatile compounds found in the wine; wines with out enough of a certain compound will lack flavor and fullness, while wines with too much of a compound can taste spoiled. These compounds result from both the alcoholic fermentation process and the malolactic fermentation, which both involve their own microbes.

One other aspect of wine flavor and aroma comes from yeast assimilable nitrogen. Yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN) is the amount of nitrogen available for yeast during the fermentation process. YAN is inherent to grapes, and can be measured after harvesting and crushing, but can also be controlled by the wine maker to reduce the likelihood of spoilage.

Microbial Processes of Vinification

Alcoholic Fermentation

Malolactic Fermentation

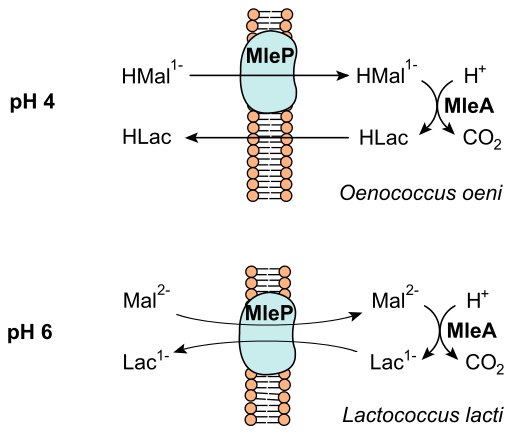

The secondary phase of fermentation is known as malolactic fermentation. Malolactic fermentation is the decarboxylation of L-malic acid to L-lactic acid through enzymatic activity. Several lactic acid bacteria can be responsible for malolactic fermentation, with varying effects on the wines flavor and aroma. Lactic acid bacteria in grape must come from the gnera Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Leuconostoc, and Oenococcus. [1]

At right is a sample image insertion. It works for any image uploaded anywhere to MicrobeWiki. The insertion code consists of:

Double brackets: [[

Filename: Ebola virus 1.jpeg

Thumbnail status: |thumb|

Pixel size: |300px|

Placement on page: |right|

Legend/credit: Electron micrograph of the Ebola Zaire virus. This was the first photo ever taken of the virus, on 10/13/1976. By Dr. F.A. Murphy, now at U.C. Davis, then at the CDC.

Closed double brackets: ]]

Other examples:

Bold

Italic

Subscript: H2O

Superscript: Fe3+

Overall paper length should be 3,000 words, with at least 3 figures with data.

Compounds That Effect Flavor and Aroma

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

Wine aroma is caused by the presence of various compounds intrinsic to the climate and fermentation process. Largely speaking, [2]

Yeast has role in production of volatile sulfur compounds through the sulfate reduction sequence pathway. The importance of sulfur compounds in wine has a tremendous effect on the sensory quality of the wine. Hydrogen sulfide can make wines smell rotten while other sulfur compounds like the flavor active thiol 3-mercaptohexanol, can impart fruity notes beneficial to the sensory quality of a wine. The wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is responsible for forming many of these volatile sulfur compounds that contribute to a wines sensory quality.

Hydrogen sulfides found in wine are formed through the metabolic pathways of yeast from inorganic sulfur compounds, sulfate and sulfite, and from organic sulfur compounds cysteine and glutathionine. Hydrogen sulfide is released from the cell as result of the sulfate reduction sequence pathway. Hydrogen sulfide is derived from the HS- ion, which serves as an intermediate stage in the reduction of sulfite and sulfate to synthesize organic sulfur compounds. The HS- ion is sequestered in the presence of a nitrogen supply to form methionine and cysteine. Thus in low nitrogen environments, sulfide gathers within the cell and be released as hydrogen sulfide. One study found

Different wine yeasts are active at different points during the fermentation process. Yeast activity also varies with varietal and starter culture used, among other things. Saccharomyces cerevisiae is shown to be the dominant yeast species in a study conducted on Bordeaux wines. S. cerevisiae grew most rapidly and was most responsible for the fermentation process. Researchers also observed that Pediococcus, Lactobacillus, and Leuconostoc species, associated with spoilage, were found in the fresh grape must, but died during the fermentation process, explaining the role fermentation plays in preservation.

The same research team also observed the growth of natural yeasts, even in the presence of an introduced culture.

Yeast Assimilable Nitrogen and Free Amino Nitrogen

Include some current research in each topic, with at least one figure showing data.

One important measure for the wine maker is yeast assimilable nitrogen (YAN). YAN is the nitrogen available in Free Amino Nitrogen, ammonia, and ammonium. Besides fermentable sugars, nitrogen availability is the primary nutrient in fermentation. YAN in critical to both the initial fermentation process and maleolactic fermentation.

YAN can be measured after harvest. Then the wine maker can account for YAN consumption allowing, and add nitrogen supplements to ensure excess nitrogen doesn’t lead to spoiling.

Further Reading

[Sample link] Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever—Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Special Pathogens Branch

References

[www.ftb.com.hrfiles/journals/1/articles/183/public/183-182-1-PB.pdf Romano, Patrizia. "Metabolic characteristics of wine strains during spontaneous and inoculated fermentation." Food Technology and Biotechnology 35 (1997): 255-260.]

Edited by Patrick Niedermeyer, a student of Nora Sullivan in BIOL168L (Microbiology) in The Keck Science Department of the Claremont Colleges Spring 2014.